By Mikhail Karadimov January 7th, 2016

I can sit here and pontificate on the arbitrariness of lists, how lists are wont to change from day to day, how insane it is that we bracket and rank something as subject as film, but I’m sure you’ve heard it all before from other, more articulate list apologists. This is the season of the list, and here I am, extending it, as Christmas continues to extend its influential reach past the realm of December, past Thanksgiving, and one day past November and Halloween itself. It’s all pitter patter. We all want to read lists, write lists, and share lists.

So…without further ado, here’s my top films of 2015, from eleven to twenty-five:

25. Furious Seven d. James Wan

It’s fun, it’s operatic, and, most importantly—something that most action blockbusters fail to achieve time and time again—it pulses with a heart too big for its own chest. La Familia is back sans Paul Walker. Brian is there, but the actor who filled everyone’s favorite police-turned-speed demon’s shoes, has past, and it’s that CGI-filled hole that brings this film so low on the list. Paul isn’t there; and once the credits come down over a theater washed with heartfelt sobs, we all know: Brian is gone, never to return to the series again. Prep your tissues, the last five minutes are an emotional doozy.

24. Carol d. Todd Haynes

We keep coming back to a train. A miniature train, with a miniature town to circle around, and with little figurines inside that town, little people. We also open up with a slow arching crane as it lifts over a busy New York street, as people bustle about. What’s the time period? The ‘50s—arguably, a simpler time. A time of peace and values, of simple lifestyles, of the homestead, of the nuclear family. Of great artifice.

With Carol director Todd Haynes—like Matthew Weiner and Mad Men—obliterates the notion of “simpler times”. In its own quiet way, the film acts as a wrecking ball crashing through the model towns of Macy’s holiday window displays. We want everything about the past to be quaint and packaged, we want to know that people were at some point capable of avoiding the complex, but the truth is: as long as there’s love and the notion of power and ownership, we will always be messy.

23. Far From the Maddening Crowd d. Thomas Vinterberg

Director Thomas Vinterberg holds firm ground in my head as a primal director. He’s more then happy at shooting for the gut. He wants you to feel the pain, and then, after that initial shock, he wants you to sit and mope in your viscera and watch the world turn red. So it was something of a puzzle to me when I heard he was responsible for the latest iteration of Thomas Hardy’s novel. I knew to put my reservation to rest as soon as I witnessed sheep run and shriek over the side of a cliff, cascading to their bloodied death below. It’s a softer Vinterberg movie, but no less potent than usual. Instead of relying on such tawdry subjects as incest and pedophilia to rouse our emotion, our ire, our sense of injustice, here Vinterberg relies on character and conflict between differing motivations, of differing philosophies, to work the audience into a fuss. But, at the same time, he knows how to lull us into blissful reverie, how to wash us in his beautiful palette and his loving composition of the Dorset countryside.

22. Durak d. Yuriy Bikov

Russia’s a fucked up place. Not as fucked up as it used to be. The violence—when it strikes—is a lot louder and not as secretive as it used to be. But the damage of the Soviet Union will forever be remembered in the cracks and fissures it left behind. So it is here, in Yuriy Bikov’s film about the confluence of business and government, that we find what it means to rape one’s community, one’s people, of their integrity and their resources, just so that a handful of crooked constituents may lead a life of undeserved and unearned opulence. It also shows what it means to go toe-to-toe with said institution, what it means to blow a whistle in Russia and point to the corruption: it means sure tragedy. It means you are an idiot. A durak.

Even though the film’s a tad overwritten and a little obvious with its message, it’s yet another brilliant—and puzzling—entry into the Russian canon of politically-conscious films.

Now, if only someone could tell me how it came to be that this and last year’s Leviathan made it past Putin and his people. Maybe the man has a better sense of humor than we assume. That, or he has no faith in art and its ability to edify. Or: he has no clue either exists. That’s how far insulated the man can get.

21. It Follows d. David Robert Mitchell

Great example of a slow burn movie. Don’t get me wrong: this isn’t a dull movie, nor is it a slowly paced movie. What I mean by calling it a “slow burn” is just how long it took for the movie to effect me. It wasn’t till I was blocks away from the theater, two cigarettes down, the winter chill setting in my bones, that I realized what David Robert Mitchell was after. Mitchell looks to scare us with the ineffable rather than the concrete. What makes Mitchell’s monster so chilling—despite its logistical contradictions—is its abstraction. Nothing scares me more than something I can’t explain, something that doesn’t make sense till it’s fatally too late to make sense of, especially when no one else is able to see that fear, that monster, that raggedy looking old lady walking naked in the distance, step by step, looking to suck my life force out. Not necessarily the most frightening horror movie of the last several years, but certainly the most thought provoking.

20. Amy d. Asif Kapadia

No movie has made me consider my role as one of the billions of members of the peanut gallery more than Asif Kapadia’s trainwreck/documentary Amy. By recontextualizing all the jokes and lampoons that the media had lobbed at singer/songwriter Amy Winehouse while she was going through her unfortunate descent into exposure hell, I realized just how cynical and hateful my laughs were back then, and how inappropriate they were. Without the fuller story, without the mélange of personal footage, as well as TMZ-inspired footage, I would have never realized just how toxic my irrational dislike was for her. And, after experiencing the film’s narrative, after watching Amy’s rapid weight loss, her incoherent bleariness, I realized that I never knew Amy Winehouse, nor did I try know her. Kapadia reveals the nastiness of our highly critical, highly toxic mentality when it comes to the super rich, the super talented, and how all we want is their magic. We want to suck on it till the vessel has dried and died. Amy Winehouse was dead years before her actual passing. And we have no one to blame for that but ourselves.

19. Room d. Lenny Abrahamson

I wish I could rank this movie higher on the list, but—as was my issue with Lenny Abrahamson’s earlier effort Frank—the movie’s pitch perfect first half is somewhat tainted by the film’s closing twenty-minutes, which wraps up Jack’s and Ma’s assimilation to life outside Room with what struck me as Hollywood precision. Suddenly, Jack grows super precocious, says all the right things, and relieves his mother’s grief with a lock of convenient metaphor. All that being said, the first half of the film is something of a miracle. Abrahamson directs the hell out of that tiny space, using the claustrophobic dimensions to his and his cast’s benefit. It also bears to mention that young thespian, Jacob Tremblay, acts circles around most other child actors, bringing a depth and pathos that one would think impossible to tease out of a seven-year-old.

18. The Martian d. Ridley Scott

Despite my irrational—and somewhat begrudging—love for Ridley Scott’s failed effort at bringing Cormac McCarthy’s 2013 script, The Counselor, to the screen, I was ready to write the nearly octogenarian director off. Alas, in swoops this adaptation of Andy Weir’s 2011 hit novel of the same name. Like a godsend, Scott’s The Martian reminds us that movies still know how to induce them blockbuster shivers. It’s funny, it’s big, it’s bold, but the movie still remembers how to zoom back in, through the ether, through the cluster, through the red sand storms, and hit upon a human being, a fragile human being, who laughs to keep the misery at bay. This blockbuster has something that most other bloated car wrecks—I’m looking at you Genisys!—refuse to include: humanity. May Scott keep the good times rolling.

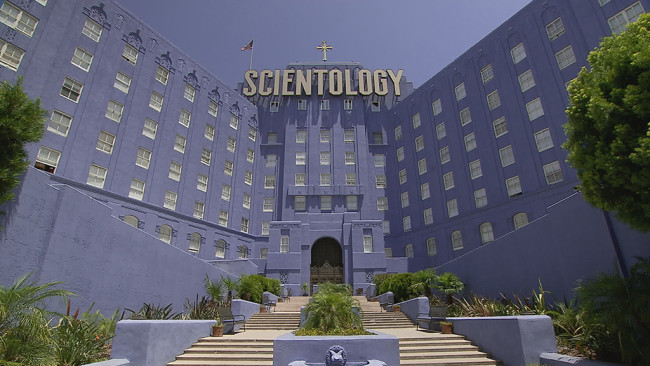

17. Going Clear: Scientology and the Prison of Belief d. Alex Gibney

What an apt title. And it doesn’t necessarily need only apply to Scientology, but any form of belief that’s corrupted or perverted into a gnarled and exploited weapon for destruction of our freedoms, our identity. Really, you can insert any other institutionalized religion into the title and it would stick just as damningly. Now, it’s difficult to say whether this film is as high as it is on this list due to my natural reluctance to accept Scientology as a legit religion—rather than a mere tax shelter—or if it’s up here for Gibney’s typical film-by-ire execution. It’s certainly a messy film, with the vaguest of through lines, but that messiness is perfectly counteracted by the deliciously salacious scandals revealed by former Scientologists. Can’t help it. The movie appeals, unabashedly, to that more tawdry side of me. Mess or no mess.

16. Anomalisa d. Charlie Kaufman & Duke Johnson

Charlie Kaufman is easily America’s most depressing filmmaker. His films are remorseless when it comes to questioning the male ego and what masculinity may or may not mean to us, whether or not its enough to satisfy our wants, our desires, our self-image, whether its enough to add spice to our everyday lives, to add nuance, to differentiate us from them, him from him, me from you, whether there’s any sense of peace in the popular notion of the male ego. With Anomalisa Kaufman seems to posit that, no, the fiction we sell ourselves of our own greatness, of our uniqueness, is nothing but a self-absorbed and bloated notion that’s defenseless to even the tiniest of pin pricks or contradictions. Satisfaction is difficult to come by, especially when a person like Michael Stone (David Thewlis) thinks himself the only one, the only voice, the only anomaly in this great wide world of ours. The film is about connections and how we sometimes do everything we can to smother and control the connections we make in our lives, and how, ultimately, once dissatisfied, sever them for good (or rather: for bad).

15. Mistress America d. Noah Baumbach

The movie bumbles about up and down the streets of New York City for some time before Baumbach and Gerwig reach through the screen and slap me silly with a whisper and a giggle, “Psst…it’s screwball! Get it?” Oooooh! It’s not till all the principle players spill into Tracey’s ex-fiancé’s Connecticut mansion, with its multitude of rooms and hideaways, that the screwball adrenaline finally shoots straight to the heart and seizes you and tickles you till you’re ready to remember and check on the state of your bladder. The movie is madcap and, ultimately, touching and honest. These characters—despite the screwball genre’s light feet and ethereal sense of fast and furious funnies (see what I did there?)—have a great sense of self that remains true to the very end. The movie is very funny and seemingly light, but the decisions it makes and holds to are not. This movie revived my hope in Baumbach. Hopefully he knows a good thing when he sees it and holds onto Gerwig.

14. Creed d. Ryan Coogler

It’s worth noting that Creed may be the most subtle soft reboot to date. Unlike Jurassic World, it refuses to rely on its built-in nostalgia as a ploy to beg for the audience’s sympathy. There aren’t any easy music cues of the tried and true score from the original nor does it recreate, like facsimile, older scenes in a rote fashion in order to manipulate our sense of wistfulness. It tweaks and it subverts. For proof, don’t look any further than the final scene where Michael B. Jordan’s Adonis Creed helps a cancer-survived Rocky up the steps of Philadelphia’s Museum of Art. The scene is injected with a newness and freshness—a brand new set of context—that succeeds in not only rehabilitating the franchise, but then progressing it, too.

13. Junun d. Paul Thomas Anderson

More than most filmmakers, Paul Thomas Anderson knows how to transport us away from our typical milieu, our time, our place. Hidden away in the high reaches of Mehrangarh Fort—in Rajasthan, India—Paul Thomas Anderson, Jonny Greenwood, and the Rajasthan Express meld together to create a spiritual experience of auditory transcendence. At no point do you feel as if Anderson is compelling you to think of issues, of greater thought, of political inaccuracies, of inner conflicts; instead, he works towards an ineffable rhythm. What he wants to show us is not an expose of human cruelty or corruption, but instead of human coalescence, in all its fluid glory. Like all his other films, Anderson shows you the brilliance of connectivity, of how strangers from disparate regions of the world are willing to come together to find that unifying hum.

12. Spotlight d. Tom McCarthy

Like Bridge of Spies, Tom McCarthy’s Spotlight might very well be the year’s most compulsively watchable movie of the year—so is the inherent trait of the procedural—which isn’t an easy feat when you consider the subject matter at hand: the abuse of power by the Roman Catholic church to cover up the pedophilic tendencies of their clergy. Even though it’s easy to be blinded by the film’s sulphurous subject line the story is much more than that. It’s also a reminder of the current state of American journalism. The film causes us to question: what is today’s standard for journalism? Do we ask enough of our journalists? Heady questions for a deceivingly simple procedural—if you ask me. Also: doesn’t hurt for the film to stand so tall upon the shoulders of its cast’s understated brilliance.

11. Sicario d. Denis Villeneuve

Rarely can I say that I was “on the edge of my seat,” but if any movie is going to claim the rights to owning my ass and dictating where it park itself and how tightly it clench, it goes to French Canadian director Denis Villeneuve’s despairing exploration of the American/Mexican border, Sicario. Boasting one of the more vigorous set pieces of the last several years, Sicario had me ducking, flinching, and squeezing my eyes shut in expectation of swift and merciless execution. My senses were on overload as I half-expected a bullet to whiz in and out of my head. No one is safe in Sicario, the audience included. Expect the sheltered nature of your life to shutter and crack under the blow of this film.

***

And in case you’re at all curious to see how the other ten spots shake out, you can listen to my top ten here where I recorded with my co-hosts James Hancock and Parker Dixon.

If you agree or disagree with my list, let me know, hit me up on twitter or facebook and we’ll talk it out.