By Mikhail Karadimov February 22nd, 2017

I wish I could start this piece with some sort of unifying theory about the “Japanese-ness” of the films I have chosen to list and address below, but I can’t. My comprehension for Japanese film is still sorely lacking. It’s not because I haven’t tried to catch up: read, watch, memorize. I’ve tried. I’m still trying. I’ve even recently started reading a copy of Donald Richie’s A Hundred Years of Japanese Film to further familiarize myself with directors like Kurosawa Akira, Ozu Yasujiro, Ichikawa Kon, Shindo Kaneto, Kobayashi Masaki, and Takeshi Kitano, and the evolution of technique and sensibility that has come to connect them all together.

Hopefully, one day I’ll be more illumined, better versed in everything related to Japanese Cinema.

Although, the question still stands—education and experience aside—why do I keep coming back to this country for my foreign language fix? What is it about the Japanese people, the Japanese culture and history, that makes me want to absorb their cinema whole?

Sadly so, I still don’t know. The answer remains ineffable.

The goal is to keep writing these small assessments—maybe even type up something about the history of Japanese cinema, moments therein—until I finally find a way to articulate my interest/obsession/hunger.

Until then: here’s a brief double bill write up of Kitano Takeshi’s Sonatine and Boiling Point (in the order I saw them):

Sonatine (1993) d. Kitano Takeshi

What if a group of gangsters went on vacation?

That seems to be the guiding principle behind funnyman-turned-serious-

Yakuza pictures are typically dominated by plot: a simple line drawn from one bloody point to another. (Yes, yes, Suzuki Seijun is an exception to the rule, but still: he’s just that: an exception.) This is not so much the case here. Tough man enforcer Aniki (Kitano) is sent on an assignment with his team of cronies to keep things from escalating into war with a rival gang. Aniki and co. are set up seaside, right on the shore, where the water’s close enough to ease you to sleep with its lapping waves.

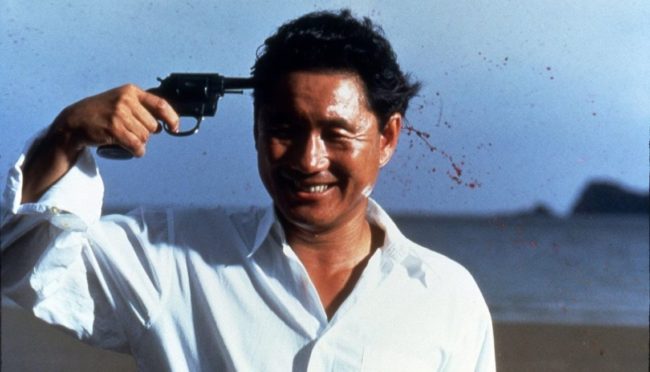

While on the beach, the gangsters find themselves idle. At ease. They don’t know what to do with their surplus of time so their emotions begin to catch up with them and unravel their sense of integrity, masculinity, self-seriousness. They thaw. Two become best buds and play pranks and games all day long—albeit, pranks and games that involve a half-loaded revolver. Aniki finds seduction, a woman who opens him up and gets him to admit that his life is one of constant fear. And we see it: we see him lash out and crack heads whenever he feels cornered, but once he’s faced with water, beach, salt, and the open air he starts to realize—and not without a degree of relief—that the life he leads, paralyzed by fear, is one of pointlessness and repetition and needs to end. Aniki finds solace in realizing there is an end to it all, and that it is in his hands—the tools one needs to make life finite.

https://youtu.be/Rr8DAG5WU4s

Boiling Point (1990) d. Kitano Takeshi

It all happened in one night: my Kitano double bill.

First came Sonatine, the experiment. I dipped my toes in and found that the water was reasonably warm, and so I slipped in the rest of the way and watched Boiling Point right after. This double bill came on the heels of another short, but encapsulating dive into Harold Lloyd and his silent comedies. There’s something to be said about the comedy in Kitano’s two gangster pictures, how they play big and with elements of slapstick—of the silent variety. There are long stretches of this film where the dialogue is secondary, especially during the laugh-out-loud baseball scenes. Instead of substantial dialogue, what we get is Yanago Yûrei’s face stonewall face of idiocy. Watching him, we watch out for the slightest twitch of awareness, of intelligence. It’s like watching a dimwitted Buster Keaton, with less bubble or exasperation, and more violence—of the lightning kind.

Taka Gadarukanaru, as the amateur baseball team’s coach, is utterly hilarious. A definite standout. The movie loses some of its steam once he disappears from the screen for the second half, when Masaki (Yanago) must leave town to find his coach a gun for retaliation purposes. That’s when Kitano shows up to fulfill his duties and implode. As he does.

And—as it turns out—as he did.

It becomes obvious by the end of the movie that Kitano is somewhat preoccupied with suicide. But grand suicide, showy suicide. Suicide of the operatic kind. In Sonatine, he destroys an entire syndicate and then—atop the food chain—returns to the beach where he “vacationed” and shoots himself in the head. Here, Masaki returns home to confront the local thugs who’ve been harassing him and does so by driving a truck full of gas right into their headquarters, blowing everything up, including himself.

From what I’ve read Kitano loves to talk death and suicide. In 1994, he was sidelined by a motorcycle accident. He sped right into a crash barrier, destroying almost half his face. Scars run along the right side. It’s worth noting that Kitano likes to refer to this accident as an “unconscious suicide attempt”. The man has destruction in him. And it shows, especially in his early yakuza films.

I have yet to watch his more experimental, self-conscious films—films like: Takeshis’ and Glory to the Filmmaker!—but as soon as I do I will be back here to offer my compare and contrast of the double-sided filmmaker.

* * * * *

If there’s one shot, one frame, that I think defines Kitano best it would be his compositions of marginalized faces and figures. More than anything else, especially if there’s wide open space all around, Kitano likes to relegate his characters’ heads and faces to the bottom corners of his shots. He will angle the camera so that people’s necks and bodies are left off screen, with the head hovering, in an open, negative space—usually framed up against the sky, as if lost in thought, floating about, the head (intellect) severed from the body (passions and immediate want).

I saw the conflict in these two movies. Especially in Sonatine, which may be the stronger, more consistent movie of the two. You see both sides: the animal, the body, the guy who knows how to kill and eviscerate, and the head, the intellect, the humor, the guy who likes to idle about and laugh. What Kitano seems to argue is that there’s no reconciling the two. If you do—or if you attempt to—you will implode, you will die or kill yourself. There’s no room for both in one human vessel. It’s theoretically and emotionally impossible.

* * * * *

That’s all for now. Hope to update you on my (symbolic) travels, my thoughts, etc., on Japanese film as I go along.