I wonder:

If people lived under water long enough would they grow gills? Would they adapt? Fish crawled out of the ocean to become dinosaurs. We crawled out of the water to become what we are now. Can it happen in reverse? If we drown enough people, will there be a baby one day, eons from now, that’s born with the power to breathe H20?

Malaysian director Ming-liang Tsai seems to enjoy such experiments. He likes to dunk his characters’ heads into full submersion to see how long they can go without breathing. Does he eventually let them back up? It depends. I think he prefers to keep them down as long as it takes to make them crack, to get them to the point where they realize that they’ve been pushing the same boulder up the same hill for what feels like an eternity. He waits till they break and cry, and then he watches them a little longer to see how they’ll continue. He lingers with his gaze, his compositions, past the point of human decency. He waits long enough to watch them fall apart. Will they die and go away, or will they resolve themselves, steel themselves till the following break down?

Tsai’s 1998 import Dong, or The Hole, concerns itself with the near future. Or rather, what was considred the near future back in ‘98. It’s a week before the turn of the millenium and the state has issued a warning to all quarantined parts of town that they will be shutting off their water. They’ve been quarantined due to the latest epidemic. People have been contracting fevers that eventually turn them into cockroaches. Not literally. This isn’t a Kafak-like (that’s right! no –esque here!) parable. Instead, people remain human while displaying cockroach-esque behavior. They lose the ability to walk, to speak, and they become ultra-sensitive to light. They scurry on all fours, on their knees and forearms, in search of darkness. They look for their holes.

Speaking of holes….

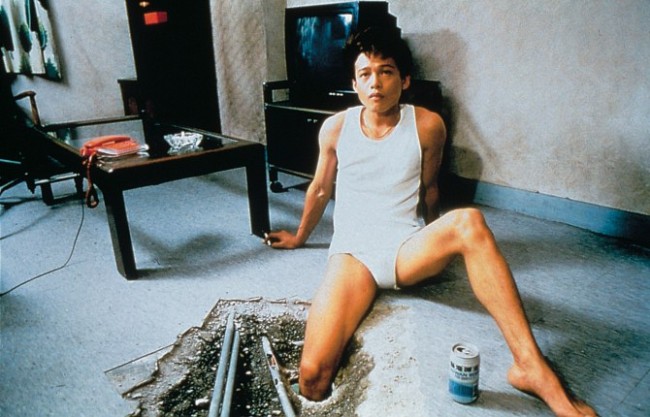

We have two unnamed protagonists in this one, a man and a woman, separated by a floor—or a ceiling (depending on your perspective)—and a hole. The hole’s chiseled in by a municipal plumber who stops by the man’s apartment to investigate why the woman’s apartment downstairs is constantly flooded. The plumber leaves the hole exposed without ever fixing any of the pipes. Stuck in their private worlds of dispair and loneliness—you know, the metaphorical hole hinted at by the movie’s title—the man and woman are forced to share a space. At first, begrudgingly. But then they come to terms with it. The voyeur in them is far too curious.

This is a world where people are discarded and forgotten; they’re habits and rituals deemed unimportant by the state lording over them. One old man wanders in search of a paste that’s been discontinued ages ago. The man from upstairs—who also owns a shop in an abandoned complex—lets the old man know about the item’s nonexistence and offers a substitute, but the old man doesn’t listen, he keeps walking along like a ghost. The paste must be somewhere. Because if there’s no paste—which he knows there isn’t—what’s the point of living? It’s a trifling matter, this paste, but it takes on new dimension, new heft, due to the dearth of significance relegated to everything else. This old man lives in a world where people dispose of their garbage by chucking it out their windows. The search for this paste is all that keeps this old man ticking. The opportunity to have a goal, to know motivation, to involve people in it and ask them for their help and their knowledge, that’s all these people have left: their hunger for familiarity, for intimacy. Intimacy that’s been distorted.

These people have no clue how to share space anymore. They’re a bunch of voyeurs. (Hitchcock would have been so proud). The man upstairs peeks through the hole in his floor, and into the woman’s living room, right at her sweaty half-naked body, and we can see the light emanating from her room, a glow of golden warmth—a potential for touch—washing over his face, as he watches her with wonder. The image is reminiscent of Psycho, but gone is the disconnect, the sociopathic distance, the analysis. Gone is the taxidermy coldness. Instead, there’s awe, there’s curiosity. But he has no clue how to communicate that. He has no clue how to simply invite this girl upstairs for dinner, for apologies, and maybe sex.

The woman downstairs isn’t any better. She hears a woman yell at an intruder a couple of floors above her and instead of doing anything about it—calling the cops, rushing upstairs, recruiting her neighbor for help—she sidles up to her window and bends her neck and listens. She hears it through the bars in her window, through the neverending monsoon. At first the woman upstairs, the disassociated voice, has power to it, she takes a stand: “Leave! I want you to go!” It plays like a scene from Rear Window, minus the visuals. But then a CRASH! sounds, and the woman changes the decibel level on her voice. The command’s the same, but the tone’s softer, less sure of itself. It sounds like the beginnings of a murder or rubbery or even rape, but the woman downstairs remains at her window looking for new angles to rubberneck. The moment’s untethered and isolated, a piece of drama, a splash of entertainment. It’s other people with other voices. It’s life. A terrible life. But it’s life. It’s presence, it’s company.

The man and the woman want the company—they need it (as everyone does…unless you’re a sociopath)—they want to be in each other’s presence, but they don’t know how to go about asking for it. Not anymore. The woman eventually finds herself upstairs and knocking on the man’s door. He’s there, inside. And she knows he’s in there. And he knows that she knows because he was just watching her through their mutual hole. But still, he hides. He makes as if he’s no longer there while the knock grows louder and louder, more urgent, more desperate. Is this a love borne out of desperation? Is this a hole that needs filling? No matter who fills it? Or is it desperation borne out of an evolutionary necessity? Are we social creatures who no longer have any clue how to socialize, how to let people in? Or are we doomed to an eternity of reticence from here on out?

Perhaps.

Maybe there’s consolation only in fantasy. In movies. In musicals. The man and the woman both have their methods for coping. Actually: they’re one and the same method. They both dream musicals. Vincente Minnelli-inspired numbers set in the same world they inhabit, the desolation, the grime still intact, but with a kind of gauze over it, streamers and balooons and sparkling lights blinding us from the disparity of reality. A dreamy gauze. Like something out of a French New Wave flick. This is where the man and the woman carry out conversations they wish they were brave enough to broach: whether or not they love each other, how they view the opposite sex, are they nuisances, are men nothing more than allergies that cause a chain reaction of sneezes, or is there something more to the Calypso and its hypnotic powers? Is this all an illusion? Are we even worthy of human contact?

Who’s to say?

Fantasy can act as a buoy, it can keep us surfaced and well above the open maw of endless ocean. We can cry and harp and beat out chests, broken, totally wasted by the idea of battling a battle we’ve knowingly lost long ago, or we can brighten the lights in our heads and escape the drudgery with some soft shoe, some tap, a finger-snapping diddly that takes us back to “more innocent times” when everything rhymed and jingled with the purity of a verse of “roses is red, violets are blue”.

This is only my second movie with Ming-liang Tsai. We’ve been courting. Slowly. Tentatively. Because, as much as I love Rebels of the Neon God, it’s a bleak experience. Hopeless. And I’m not sure if this movie’s just as hopeless or not. By the film’s end, the man upstairs pulls the woman downstairs from her sinking ship, he lifts her with his brightly lit arm, like an arm out of heaven come to pluck its newly fallen angel. But you don’t know for sure. It might be fantasy. The epidemic might have already swallowed her, driven her into a hole. Maybe it’s only fantasy we see when the woman ascends into the light, a fantasy transformed into reality by the combined power of imagination and darkness. Maybe all we need are holes. We need somewhere to hide and forget as we watch our movies, whistle our tunes, and go la-di-da as our existence disappears from us.

I hope not.