By James Hancock August 12th, 2015

With the release of the first teaser to Quentin Tarantino’s The H8ful Eight, I’m feeling a little western fever, in particular for the spaghetti westerns of Sergio Corbucci, a neglected master whose work has been inspiring Tarantino for many years. When people say spaghetti western, just about everyone immediately thinks of Sergio Leone and rightfully so; the man was the undisputed master of the western as grand opera. But Sergio Corbucci is another type of filmmaker entirely. There is a vicious, sadistic streak in his work that only grew with time to the point where one is hard pressed to find any character in his films deserving of the label ‘hero’. I recently indulged myself in a bit of a Sergio Corbucci marathon where I saw eight of his most famous westerns for the first time and while I still have a few more essentials to hunt down, I want to share some highlights from the man’s career for those moviegoers out there who might go insane being forced to wait until December for a chance to see The H8ful Eight. Corbucci’s work can be difficult to find in some cases, but I assure you that each and every film of his I’ve seen is worth the effort. He is one of the great directors of the 1960s and deserves a far loftier position in film history than simply being referred to as the other Sergio.

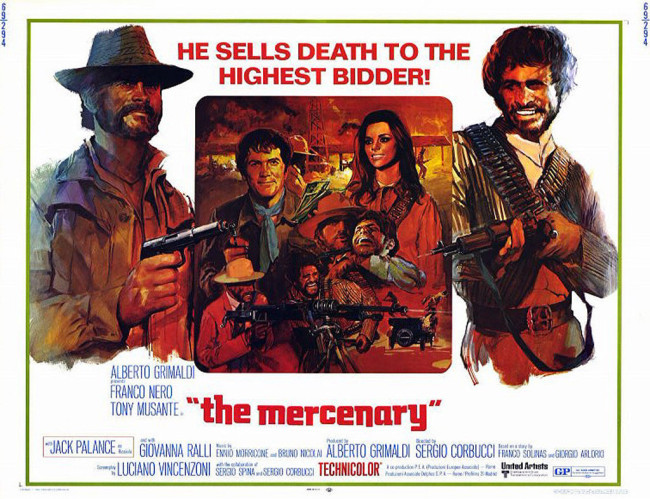

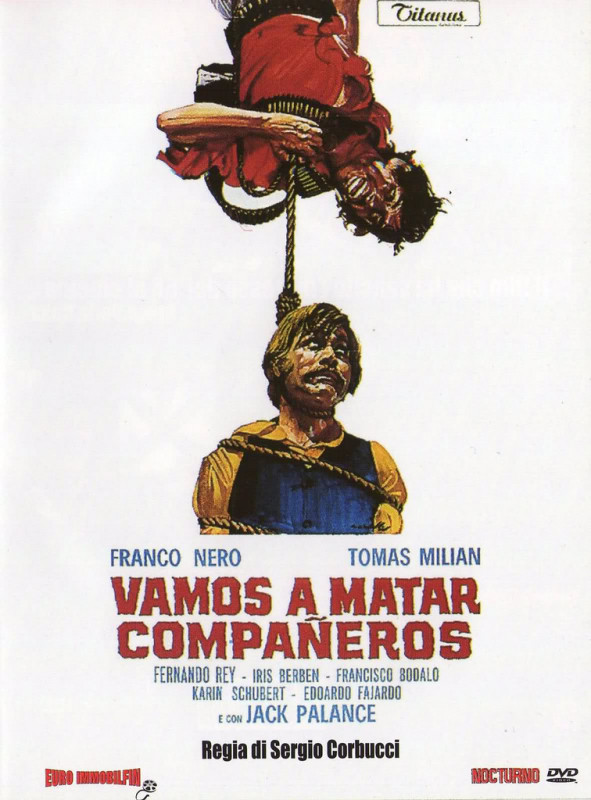

If you’ve enjoyed Tarantino’s 21st century work such as Kill Bill: Vols. I & II (2003-04), Inglourious Basterds (2009) or Django Unchained (2012), you’re already familiar with Corbucci’s movies even though you didn’t realize it at the time. As we all know, rather than trust a composer with the soul of his movies, Tarantino often chooses to sample music from his favorite films of the past. As I watched Corbucci’s movies, I couldn’t help but have intense flashbacks from Tarantino’s movies which have so memorably used music from Django (1966), Navajo Joe (1966), Hellbenders (1967), A Professional Gun aka The Mercenary (1968) and probably more that I didn’t catch on the first viewing. Some of Tarantino’s critics will likely repeat their ridiculous complaint that Tarantino ‘stole’ the music. As Tarantino has often stated in the past, he didn’t steal anything. Composers such as Ennio Morricone, Bruno Nicolai, & Luis Bacalov were all well paid for the use of their compositions. I can’t emphasize enough just how effective the music is in the world of Corbucci. In some cases (Navajo Joe and Compañeros (1970)) the music acts almost like a Greek chorus commenting on the story by singing the name of the movie repeatedly as the central characters busy themselves laying waste to their enemies. The intense savagery of Corbucci’s films will make them tough to digest for some viewers but I’d argue that all of his best work is worth viewing just for the brilliant scores alone.

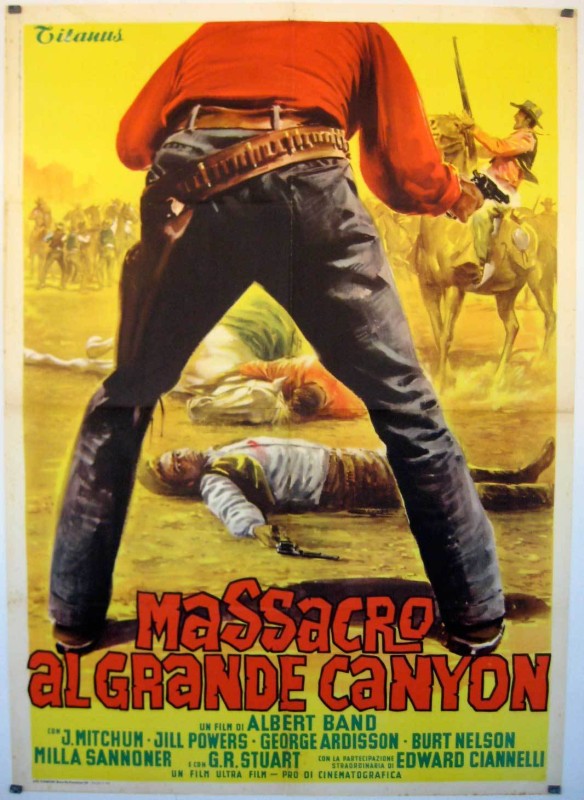

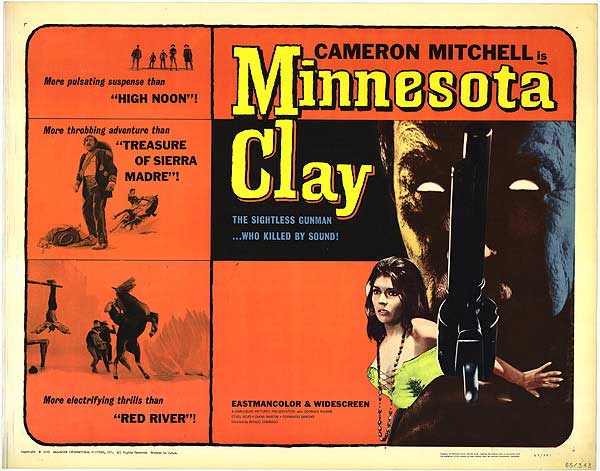

In the video above, Tarantino introduces one of Corbucci’s earliest films in the western genre, Minnesota Clay (1964). We’re lucky this video exists at all in that Tarantino throws out one person attempting to record the presentation. What’s great about the video is how Tarantino breaks down Corbucci’s westerns into four periods: classical (heavily influenced by American westerns of the 50s), his spaghetti westerns, the Mexican Revolution Trilogy, and finally Corbucci’s 70s counter-culture hippie westerns. I still have a lot of holes in my game when it comes to discussing Corbucci but from the eight films I have seen, I am astonished by how rapidly his filmmaking style and storytelling sensibility evolved in such a short period of time all while working in the same genre. Prior to dipping his toes into the western genre, Corbucci spent several years directing sword and sandal films before co-directing Grand Canyon Massacre (1964) under the pseudonym Stanley Corbett. In the same year he directed Minnesota Clay, a very solid albeit traditional western. According to Tarantino he feels that Corbucci would have continued on this path if not for the fact that in the same year Sergio Leone released his first spaghetti western A Fistful of Dollars (1964).

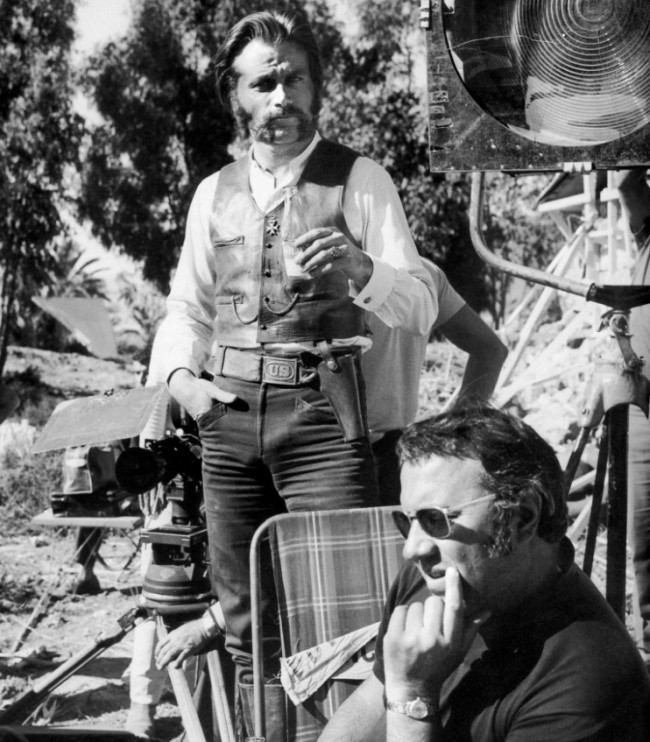

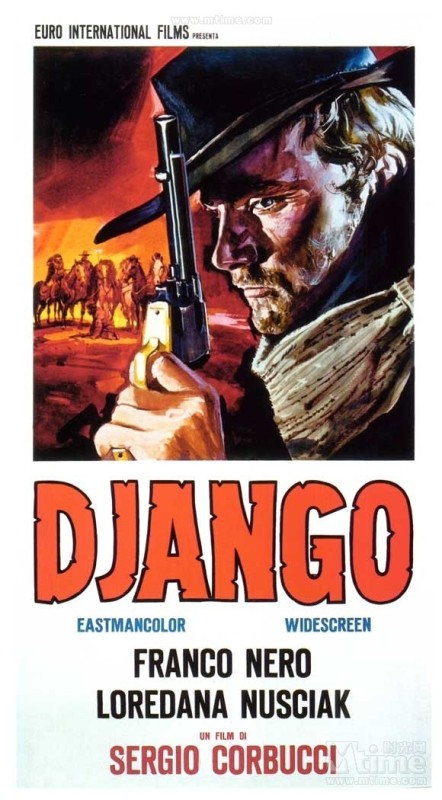

To say A Fistful of Dollars was a game changer doesn’t nearly cover it. The film sparked a stampede of spaghetti westerns that would change the genre forever. Every movie fan has their own definition of what a spaghetti western means to them, but we can all agree that spaghetti westerns share a surrealistic sensibility with hyper-stylized visuals that were a total departure from the Hollywood westerns of the 1950s being made by directors like John Ford, Howard Hawks, Anthony Mann and Budd Boetticher to name but a few. Corbucci immediately decided to put his own personal stamp on the new genre with the unforgettable Django, a movie so popular it spawned over thirty unofficial, unsanctioned sequels including Tarantino’s own Django Unchained. Corbucci’s Django starred Franco Nero in the title role and the two men would continue to work together for many years to come. Corbucci’s spaghetti westerns are absolutely ruthless. When I think of his movies I think of graveyards, buzzards hovering overhead, endless massacres, the strong torturing the weak, and larger-than-life figures capable of single-handedly fighting entire armies. In Corbucci’s world, people tend to fall into two categories of either being psychopaths or victims. At best characters like Django are anti-heroes who if they do something good or noble it is only because it is in their own self interest.

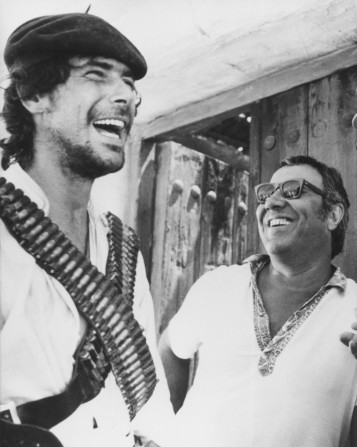

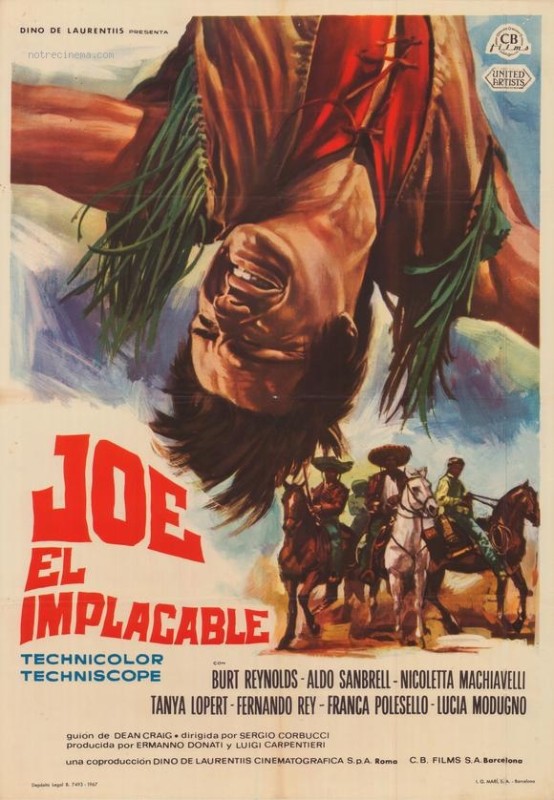

Nearly every western by Corbucci features an eclectic mix of killers, rapists and murderers whether they are bloodthirsty bounty hunters or rampaging bandits. Periodically they collide with an individual capable of godlike levels of mayhem and you have a situation like Navajo Joe where Burt Reynolds goes on the warpath slaughtering men by the dozen for revenge after they murder his tribe. Seeing Navajo Joe has forced me to look at Burt Reynolds in a completely new light. He delivers what might be the most athletic performance by an actor since the days of Buster Keaton. But the real discovery for me in watching Corbucci was The Great Silence aka Il Grande Silenzio (1968), the most nihilistic western ever made and I say that fully appreciative of the dark depths explored by Peckinpah in Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia (1974). The Great Silence takes place in a bleak snowbound landscape and tells the story of a mute played by Jean-Louis Trintingnant, a killer with a code who only kills in self defense, specifically the corrupt bounty hunters plaguing the area. Klaus Kinski chews the scenery as his adversary and watching these two titans of European cinema go head to head is the most fun I’ve had watching movies in a long time. If you enjoyed the training sequences in the snow in Django Unchained or need to scratch the itch to see The H8ful Eight, the closest you can get right now is by watching The Great Silence, the darkest western I’ve ever seen.

As I did my homework for this post, I realized that it is not technically accurate to say that I was a virgin to Corbucci before my recent Corbucci marathon (and trust me, if you haven’t seen his movies, you are still a virgin in a sense). I barely remember this particular film but as a very young child I repeatedly watched a movie called Super Fuzz (1980) on HBO. The movie is about a cop with superpowers who loses them every time he sees the color red. I absolutely loved it at age 4 or 5 but having now revisited some scenes on YouTube, I’m going to let that childhood memory remain in the past and not shatter it by revisiting the movie with my now jaded perspective. But it is comforting in a weird way to know that I was exposed to Corbucci at a very impressionable age. As I get older it becomes increasingly difficult due to time constraints or just plain stubbornness to discover new filmmakers that become part of my personal pantheon of favorite directors. When I was in college it seemed like every day I was discovering some great master of the past whose filmography commanded my attention, but over time this pleasure of discovery occurs less and less frequently. Until a few days ago I had in a way resigned myself simply to filling in the gaps of my knowledge of those great directors whose movies I have yet to see. Corbucci’s movies have totally exploded that notion. Discovering Sergio Corbucci’s westerns at age 39 has been my great moviegoing delight of the year and proof that with a little digging there are always brilliant directors just waiting to be rediscovered. Some say that Corbucci was the 2nd best director of spaghetti westerns. Some will argue that he was the best European director of westerns. I’m just going to state that I think he is one of the best directors to work in the western genre ever and leave it at that. I have no idea if the movies he made before or after his westerns are worth watching or if they will diminish my opinion of him. All I know is that Sergio Corbucci told unforgettable stories in a manner that had never been seen before, several of which now rank among my favorite westerns. From my biased, increasingly stubborn perspective, that is the stuff of greatness.

I am one of the Co-Hosts of Wrong Reel and you can find our content here:

Join the Conversation on Twitter

The Westerns of Sergio Corbucci I have seen to date.

‘Vamos a Matar Compañeros’ Theme Song by Ennio Morricone