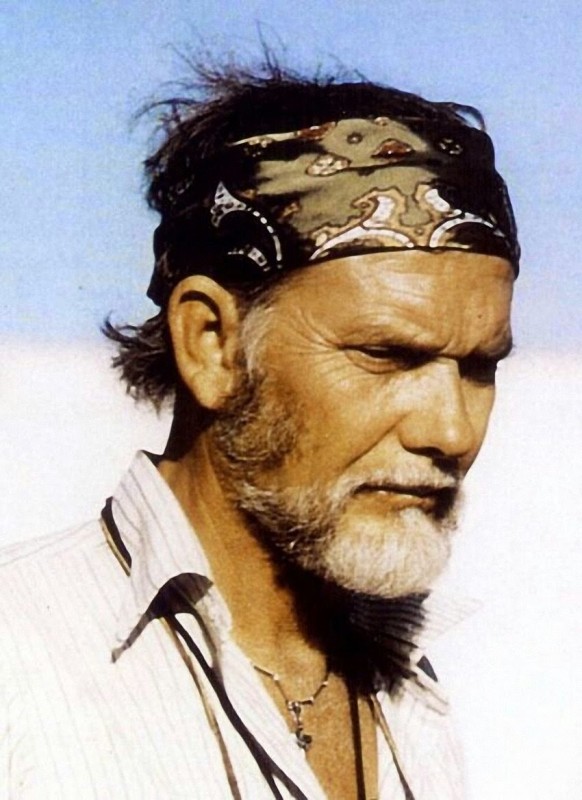

Sam Peckinpah is one of the great tragic figures of film history, tragic in the sense that he was one of the greatest filmmakers ever to step behind a camera only to have his career cut short after many dark years of drug and alcohol abuse as well as near-violent confrontations with the studios and producers that he worked with. His friends and closest collaborators speak of him with nothing but love and respect, but nearly everyone that was exposed to Sam Peckinpah has a favorite story to share about his unpredictable destructive side that eventually came to overshadow the latter part of his career. Over the last twenty years I’ve spent a lot of time watching his films and for me he consistently ranks alongside Orson Welles and Howard Hawks as one of my favorite filmmakers. He fearlessly explored the darkness in men’s souls and the horrors they are capable of yet I can think of few filmmakers capable of matching the breathtaking beauty of the more poetic scenes from his films. The story of his personal life is equally fascinating as most documentaries and books about him reveal in intimate detail. Tackling Peckinpah in a concise, easily digestible blog post is next to impossible, at least for me. One day when I’m ready I’ll attempt a deep dive into his career, and his tortured personal life. What I’m offering today is only a small glimpse of Peckinpah’s mythic stature as a filmmaker in order to call attention to what is for me his most interesting work. For anyone who is still a virgin to his films (and trust me, if you haven’t watched them, you’re a virgin) welcome to the world of Bloody Sam Peckinpah.

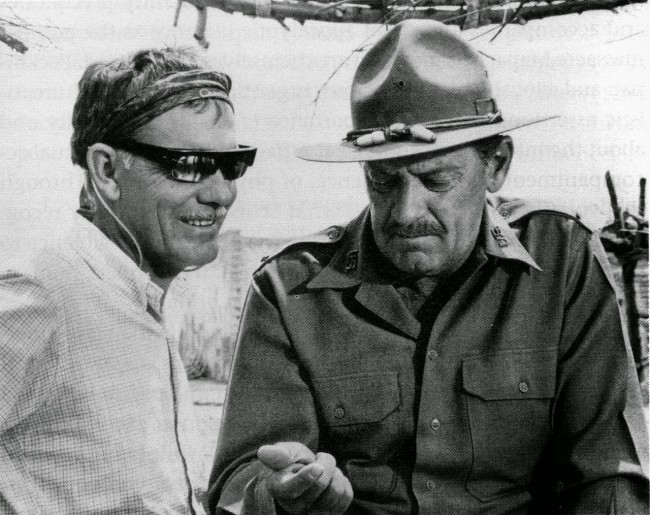

In nearly all of Peckinpah’s films there is an undeniable yearning for the simpler, less civilized days of the past. Whether his stories take place in the 1880s like Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid or the 1970s like Convoy, there is the sense that the world is rapidly becoming a place where the untamable men that Peckinpah admires, men who follow a particular code that only Peckinpah can fully articulate, no longer belong. The film that best embodies this sense of fatalism and dismay about the future and the evils of civilization is his most famous work, The Wild Bunch (1969). As film critic Elvis Mitchell once put it (I’m paraphrasing), this is a film that is so hardcore that when the Director’s Cut was finally released in the 1990s, a quarter century after its initial release, the film was rated “X” (was later appealed). The concept is classic. A well organized group of outlaws in 1913 find that the Wild West is fading fast and they decide to attempt one last train robbery with the men and resources they still have at their disposal before age, the law and time catch up with them. This movie served as my introduction to Peckinpah and I’ve seen it many times since in multiple theaters and just about every home viewing format imaginable including my original widescreen copy of the Director’s Cut on VHS. On the surface, The Wild Bunch might sound like a conventional western but Peckinpah’s handling of the material elevates it to the sublime with one of the most poetic yet brutal depictions of the West in the history of film. If Ernest Hemingway had been a filmmaker instead of a novelist and had decided to make a western, the result would have likely resembled The Wild Bunch. Just thinking about some of my favorite scenes, I get chills down my arms and up my spine. In college I’d threaten my friends with violence if they spoke or distracted me during those sequences. From start to finish, the dialogue, the acting, the photography, and the music are unforgettable and if I were ever backed into a corner about limiting myself to only one movie that I could watch for eternity, there’s be a very good chance I’d pick The Wild Bunch.

Before moving on I do have to share one anecdote that actor L.Q. Jones shared with us at a 70 mm screening ofThe Wild Bunch at the Egyptian in LA about fifteen years ago. L.Q. Jones worked with Peckinpah many times and he plays T.C. in The Wild Bunch. One night while they were shooting in Mexico, Peckinpah and some of his cast were returning to their hotel after wrapping for the day. Peckinpah insisted upon stopping in some roadside bar that looked as if they might never emerge with their hides intact. Dutifully actors William Holden, Ben Johnson and L.Q. Jones followed Peckinpah inside where before long Peckinpah started a fight. As weapons were pulled, the actors did their best not to get their throats cut and eventually the scuffle died down. As the dust settled, the actors looked in vain for Peckinpah only to learn that during the melee, Peckinpah had snuck outside and asked their driver to take him back to the hotel leaving his actors behind to fend for themselves. To what extent the details of this story are 100% accurate, I have no way of knowing, but the story is very consistent with Peckinpah’s mythic hell raising.

After The Wild Bunch, Peckinpah became one of the most notorious and recognizable directors in the film industry with an undeserved reputation for using film to wallow in violence and cruelty. The reputation would prove to be a double-edged sword for Peckinpah the rest of his career, making him bankable to the studios and reviled by his critics. With his next film, Peckinpah sought to leave his reputation behind him with The Ballad of Cable Hogue (1970). The Ballad of Cable Hogue is a gentle fable about a man who discovers water where there was thought to be none. He builds a successful business from his discovery and to top it off he manages to fall in love along the way. Filled with comedy and music, the film is the most unusual stylistically of Peckinpah’s career, a film director John Huston once described as “the most wayward film he had ever seen”. The film is relatively unknown outside of the circle of hardcore Peckinpah fanatics, underlining a problem that would haunt Peckinpah moving forward with his career. The Ballad of Cable Hogue and Junior Bonner were both character driven stories with relatively little violence to speak of and both films underperformed at the box office compared to his other work. In spite of how much Peckinpah was criticized publicly for the content of his films, people showed up in droves to see what his more controversial stories had to offer. With that in mind, for his next project, he would take the curiosity and appetites of his audience to the limits and beyond with one of his most scandalous movies, Straw Dogs.

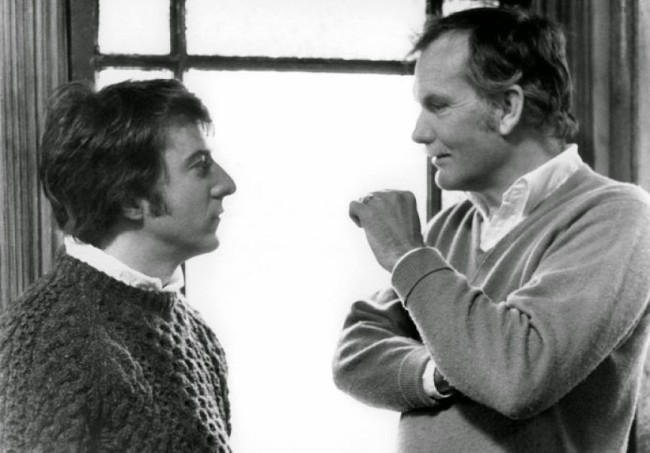

There are few trends I hate more in the movie business than the recent wave of toned down, defanged and declawed remakes of established classics in order to try and make them more palatable to a wider audience. We’ve seen this trend in horror, science fiction and also unfortunately with Straw Dogs, one of the best films of the 1970s. So please forget the 2011 remake ever happened and sink your teeth into this traumatizing movie that I regard as a masterpiece. The story follows an intelligent but unassertive American played by Dustin Hoffman who moves back to the English village where his English wife was raised. Many of the local lads still have a thing for her and before long Hoffman and his wife find themselves harassed, physically assaulted and eventually under siege in their own home. The conflict escalates into some of the most brutal violence ever caught on film as Hoffman struggles to defend his wife and property. This film is not for everybody. One of the most controversial scenes involves a rape where actress Susan George expresses an eerie range of conflicting emotions as she grudgingly gives in to the sexual assault of an old boyfriend only to have the situation spiral horribly out of control. Peckinpah’s reputation for misogyny with his critics was only further enflamed by this film. Nonetheless, this is raw powerful cinema and required viewing for any fan of Peckinpah’s work.

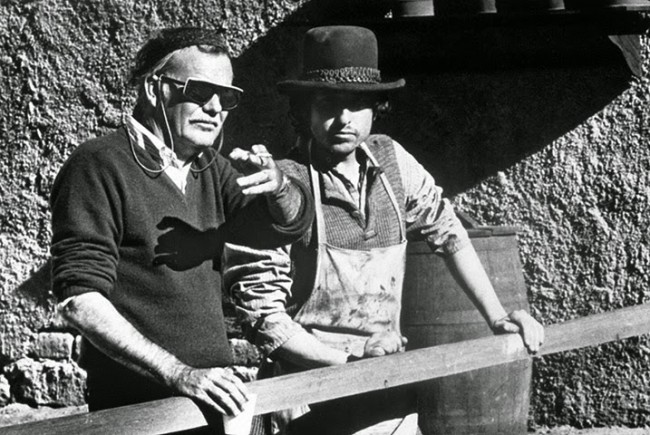

Finally we come to my favorite film by Sam Peckinpah, Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid (1973). I know of at least 3 different versions of this film in circulation but in my opinion the 1988 restored version of Peckinpah’s work-in-progress print is an undeniable classic. Peckinpah unfortunately lost control over the project back in the early 1970s and MGM decided to release a truncated version of the film in a short sighted effort to cash in on the rep Peckinpah earned on The Wild Bunch and The Getaway (1972). The studio left all the heart and soul of the film on the cutting room floor and focused entirely on shoot outs. In the documentary Z Channel: A Magnificent Obsession (2004), there is a great chapter in the special features covering the discovery and exhibition of the 1988 work in progress print. Essentially one of Peckinpah’s biker/outlaw friends had it under his house and was safeguarding it after Peckinpah’s death. Some fans came to meet him about showing it in public when someone began firing a gun through the windows as if they were trapped some deranged scenario out of one of Peckinpah’s movies. Thankfully this cut of the film survives in that Peckinpah never was allowed to finish editing and mixing the film. This is the closest we will ever get to his vision for the movie. There is a third version cut by editor/film historian Paul Seydor in 2005 and while many love this cut of the film, it is not the one I watch when I want to immerse myself in this movie. The special edition dvd includes both the 2005 and 1988 cuts of the film while the butchered version from the 1970s is increasingly difficult to find.

Moving on to the film itself, Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid is not the epic that is The Wild Bunch but rather a sad, haunting story about a man hunting down and killing the best friend he ever had. With gorgeous cinematography by John Coquillon and a score composed by Bob Dylan, this movie looks and feels like no other movie ever made. I love the laid back pace of the movie with many scenes of grizzled old killers talking about nothing in particular while sharing a bottle of whiskey. For me this story is Peckinpah’s purest statement on the death of the Wild West and he ropes in just about every actor he had ever worked from his unique troupe of actors (Chill Wills, R.G. Armstrong, Jason Robards, L.Q. Jones and more) to make cameos throughout this amazing movie. Peckinpah himself makes a cameo toward the finale where he turns down a drink from Garrett. The hidden joke is that Peckinpah never turned down a drink in his life but at that point in the story Garrett has compromised himself in so many ways that has effectively betrayed every value that Peckinpah holds dear. Is the movie better than The Wild Bunch? That’s up to individual viewers to decide but I can safely say that this film belongs in the pantheon of the greatest westerns ever made. This also marked the beginning of the period of Sam’s life when his dependency on alcohol and eventually drugs would get the better of him. He jokingly referred to himself as a functional alcoholic but James Coburn has spoken at length about some of the problems on this production. One drunken episode made its way into the movie. During the shoot, James Coburn found Peckinpah firing a gun at his own reflection in a large mirror in his hotel room. Never to let an interesting dramatic beat slide, they put the moment into the film at the finale. After killing Billy, Garrett is completely disgusted with himself, he turns to his own reflection and opens fire. The moment is particularly telling in that is sums up a lot of Peckinpah’s behavior throughout the rest of his career.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HzAN5qkVOZY

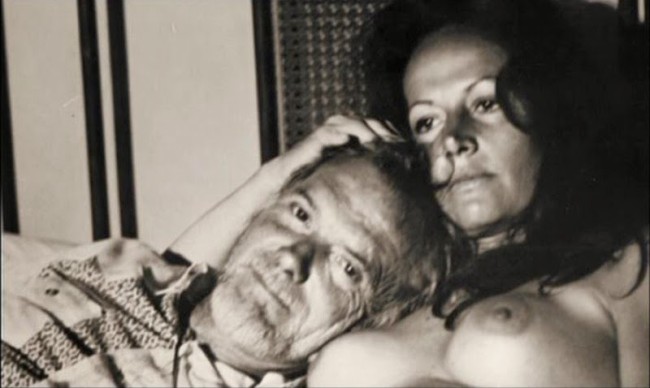

The last film I want to talk about is Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia (1974), arguably the darkest, bleakest film Peckinpah ever made. The film stars Warren Oates in the performance of his career (he basically plays Peckinpah) as Bennie, a man trying to collect a $1 million bounty on a man that has impregnated the daughter of a corrupt Mexican rancher. Brutal and uncompromising from start to finish Bennie’s quest to earn some fast cash ruins his life culminating in a murderous rampage where he guns down everyone involved in the rancher’s organization. This is not a date movie. This is pure grind house cinema that is best watched when one is ready to go to the dark side with a bottle of booze in one hand and some kind of weapon in the other. Flawed it may be, but once you start watching it you won’t be able to look away. In spite of all the savagery of the film, the movie features some intimate scenes between Warren Oates and Isela Vega where one gets the sense that we are seeing Peckinpah’s idea of true love. The love isn’t complicated. It consists of nothing more than lounging beneath a tree with a bottle of booze, resting his head on a beautiful woman. Sadly this state of bliss is never meant to last.

The more I write the more I realize that discussing Peckinpah in a brief cogent manner is next to impossible. There is too much amazing material, too many incredible anecdotes and too many classic movies. I hope this guide will serve as a useful introduction but there is so much more to him than just these films. Many Peckinpah devotees will cry foul at the omission of Ride the High Country (1962), Major Dundee (1965), Junior Bonner (1972) and The Getaway (1972). Hardcore purists will also berate me for leaving out his incredible work in television like The Rifleman (1958-59) and Noon Wine (1966). For anyone who wants to know more I recommend Paul Seydor’s bookPeckinpah: The Western Films – A Reconsideration as well as Marshall Fine’s Blood Sam: The Life and Films of Sam Peckinpah. There are several excellent documentaries on his career as well. Special mention goes to Sam Peckonpah: Man of Iron, a comprehensive documentary by the BBC from 1993. So if you’re embarking on learning about Peckinpah for the first time, I envy you. Like all great filmmakers, he is in a class all by himself, a man who carved out a chapter of film history that I find endlessly rewarding every time I revisit any of his movies.

I am one of the Co-Hosts of the podcast Wrong Reel and you can find our material here: