By James Hancock July 5th, 2015

There’s a transcendent sequence in F for Fake (1973) where Orson Welles offers one of the best observations about art and authorship I’ve ever heard. If you wish to see the entire sequence I urge you to watch that movie as many times as humanly possible but I will share a fragment for the purposes of this post. In reference to Chartres Cathedral, Orson says, “This has been standing here for centuries. The premier work of man perhaps in the whole Western world, and it’s without a signature.” What interests me about this idea is how it completely flies in the face of my normal approach to studying film history. Orson Welles was far more preoccupied with appreciating great art for its own sake rather than obsessively pouring over the biography of the artist responsible. Welles likely had his priorities in the right place. When it comes to film history, I tend to place great directors on a pedestal and hero worship them completely out of proportion often spending more time learning about their lives than about their actual work. Certain larger-than-life directors like Orson Welles, Sam Peckinpah, Werner Herzog, John Huston, & Samuel Fuller seemingly live the lives of one hundred men, and their personal exploits are part of the fun and excitement of studying their films. But every once in a while I come across a director whose life is a total mystery with very few resources available for learning about them apart from the obvious route of just examining their work. Anthony Mann is one of those directors. For the last few days I’ve been on a bit of a rampage aggressively watching Anthony Mann’s films and during that time, as usual, I scoured the internet for books, essays, etc. about his life only to come up, surprisingly, with very little material. Maybe one day I’ll be lucky enough to stumble across a comprehensive biography of his career but for now I’m going to defer to the wisdom of Orson Welles and simply focus on his extraordinary films. I’m only just starting to realize what a grave error I’ve made in overlooking this incredible filmmaker for so many years.

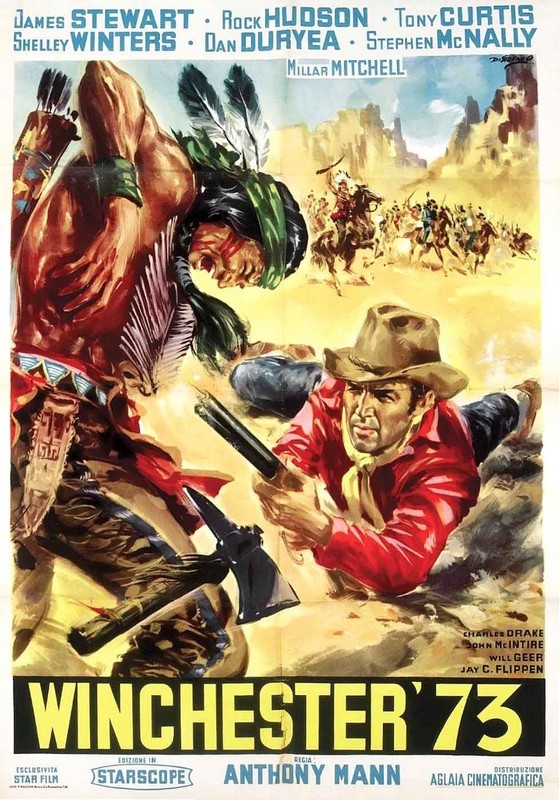

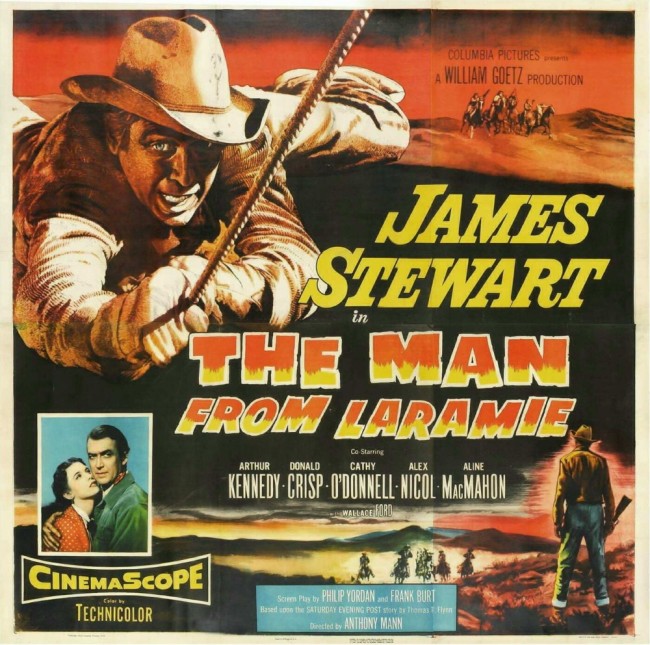

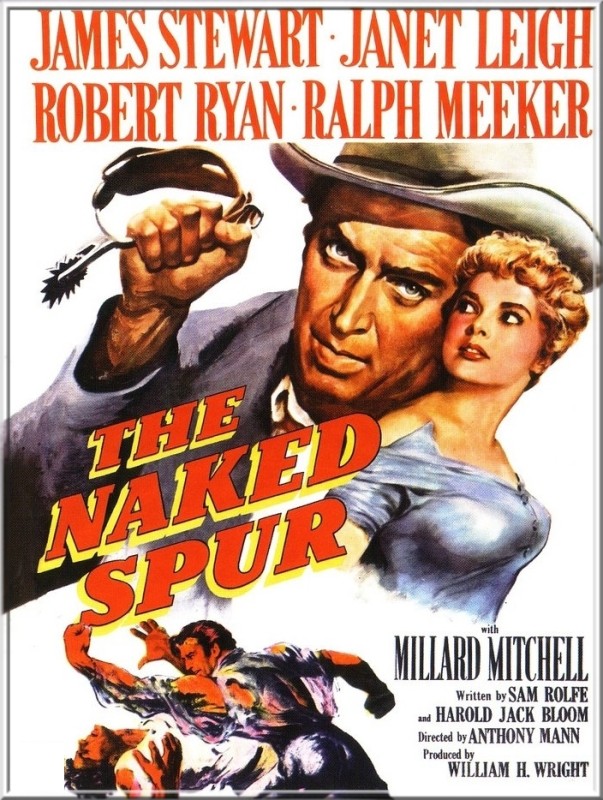

For those of you unfamiliar with Anthony Mann, he got his start in the early 1940s as an assistant director working on films like Sullivan’s Travels (1941, Preston Sturges). He quickly made the jump to the director’s chair and made important contributions to film noir in the late 1940s before becoming one of the most successful directors in Hollywood eventually helming several big budget historical epics in the early 1960s. But his most fascinating contributions to cinema were undeniably made with westerns. When film fanatics discuss westerns, a few familiar names tend to come up very quickly such as John Ford, Howard Hawks, Sergio Leone, and Sam Peckinpah. Western fanatics enjoy friendly debates over which of these directors were the best and aficionados of the genre often spend years obsessing over their work before ever feeling the need to come up for air. But when it comes to Anthony Mann, I’ve never felt compelled to place him in their company primarily because I didn’t know a thing about him other than the fact that filmmakers like Martin Scorsese and Quentin Tarantino hold him in very high regard. Over the years, I’ve periodically chipped away at his filmography but having now seen Winchester ’73 (1950), The Furies (1950), The Naked Spur (1953), The Far Country (1954), The Man from Laramie (1955), The Tin Star (1957), & Man of the West (1958), I finally slapped myself in the face and realized that for years I’ve been underestimating a man who belongs in the pantheon of great directors.

Film Noir

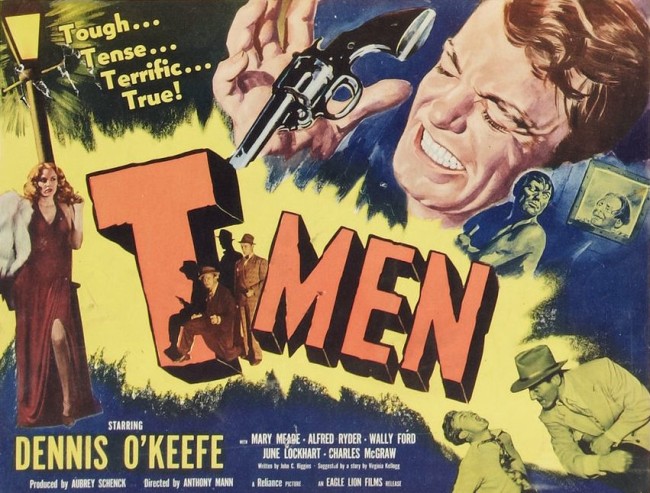

Many ingredients go into a great film noir from femme fatales to hardboiled detectives but first and foremost when I think of great film noir I think of a specific visual style of high contrast lighting and dark ominous shadow play. Working with legendary director of photography John Alton (author of Painting with Light), Mann directed some of the most visually distinctive B-movies from the late 1940s, the most memorable of which are T-Men (1947) and Raw Deal (1948). It was during this period that Mann learned the value of finding strong collaborators and sticking with them over several films. Screenwriters like John C. Higgins & Borden Chase would both write several movies for Mann. But his most important collaborator was actor James Stewart and in 1950 they made their first of eight movies together, Winchester ’73.

The Westerns

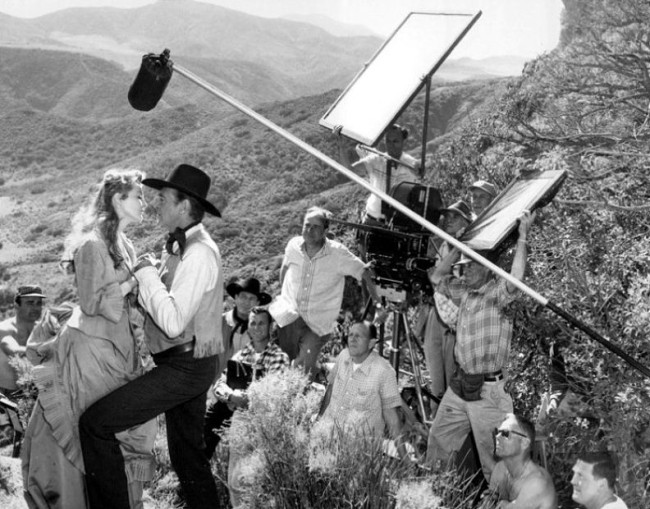

Every great director of westerns leaves a signature on their style of storytelling. Howard Hawks knew the value of great dialogue, Sergio Leone turned the western into grand opera and Peckinpah obsessed over tragic figures unable to adapt to changing times. For Anthony Mann, his preoccupation was psychology. His westerns feature complex Shakespearian struggles with characters often crippled by self loathing, hate, doubt and lust. Anyone looking for simple heroic tales of good versus evil best look elsewhere; there’s no such thing in Anthony Mann’s universe. Even the majestic mountains so often featured in his westerns take on new dimensions, almost seeming to mock the characters as they struggle in vain against one another to survive in the inhospitable West. Some of the best actors of the Golden Age of Hollywood broke new ground under Anthony Mann’s direction playing characters almost completely unrecognizable from the parts that made them legends in their own time. Working with Mann, actors such Gary Cooper, Henry Fonda, Barbara Stanwyck and James Stewart embraced dark, haunted personas that I find to be some of the most interesting of their careers.

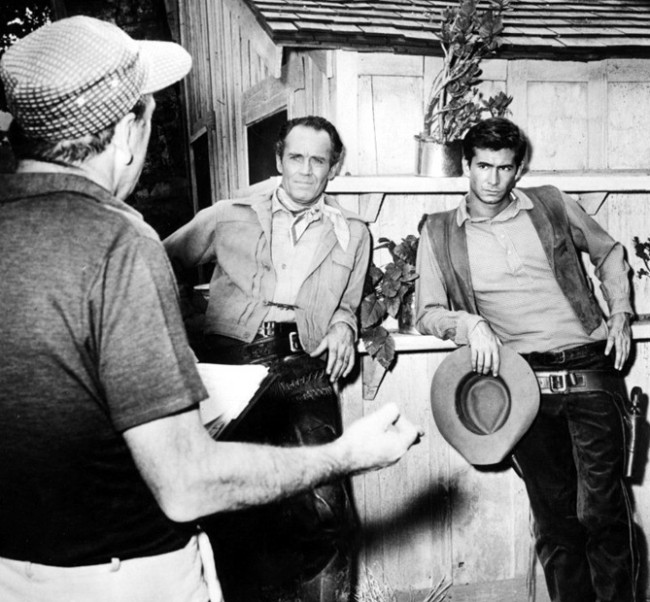

Without going into too much spoiler territory, I do want to pitch a few of these remarkable westerns for anyone considering checking them out. The Furies stars the powerful Barbara Stanwyck in a fierce role that would make John Wayne envious. Featuring the best black and white cinematography of any western I have ever seen, The Furies is an undeniable masterpiece that has thankfully been restored and made available by the Criterion Collection. The Tin Star is a movie worthy of Akira Kurosawa with Henry Fonda taking Anthony Perkins under his wing as an apprentice to teach him the tools of the trade to be an effective sheriff. Man of the West is perhaps Mann’s darkest western with Gary Cooper as an aging outlaw trying to break free once and for all from his surrogate father played to perfection by Lee J. Cobb. And then there are the many collaborations with James Stewart, all of which are essential westerns, but if I had to pick a favorite, I’d lean toward The Man from Laramie, the one Mann film I have been lucky enough to catch in the theater.

The Epics

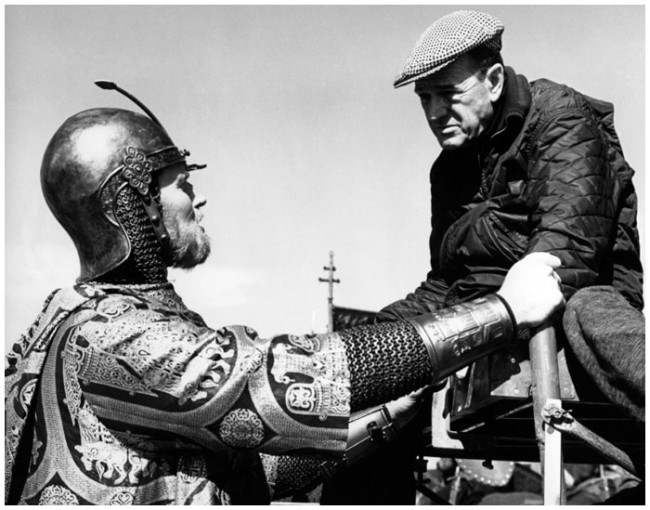

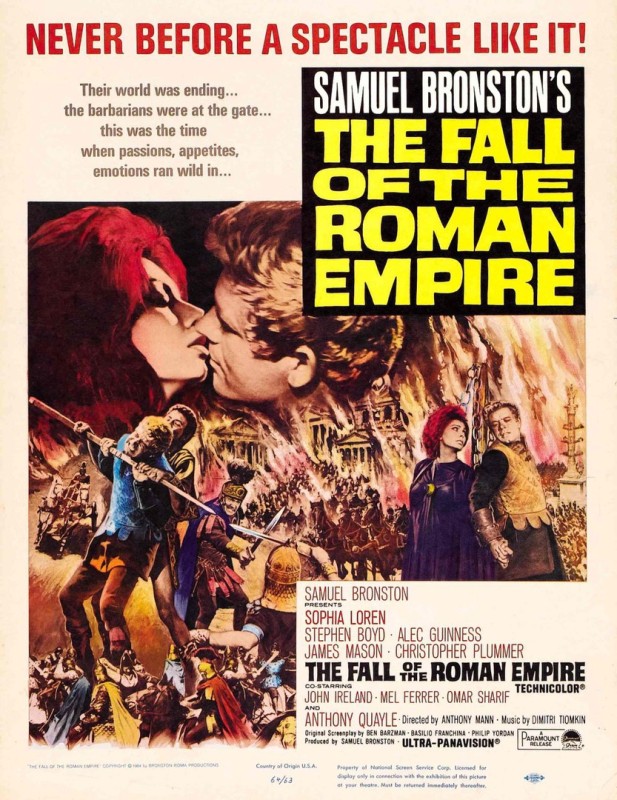

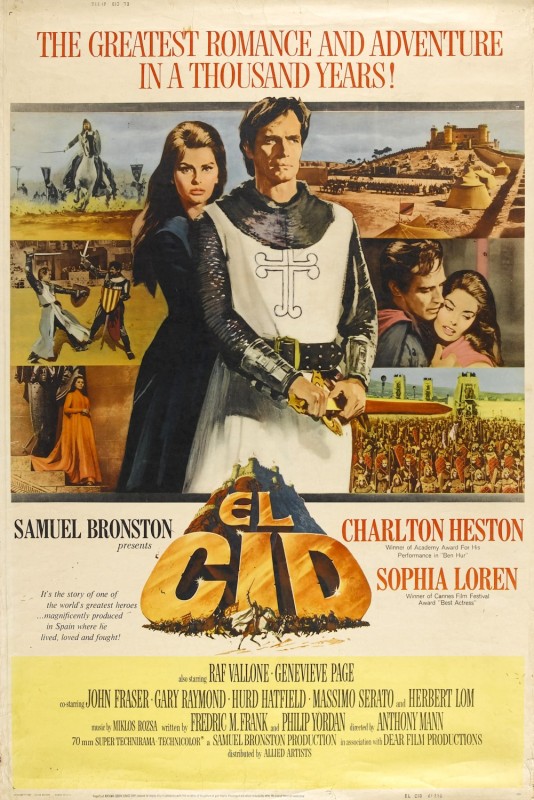

Anthony Mann entered a new stage of his career with his brief association with the film Spartacus (1960). Frustrated over not being cast in Ben-Hur (1960, William Wyler), actor Kirk Douglas decided to produce an historical epic in which he could star. He first offered the role of director to David Lean but when Lean passed, the job went to Anthony Mann. For reasons that are debated depending upon whose story one chooses to believe, Anthony Mann was fired after the first week’s shooting. Rather than take this dismissal sitting down, Anthony Mann bounced back with one of the best films of his career, the historical epic El Cid (1961). So many historical epics from the 1950s and early 1960s, with their casts of thousands and over-the-top production value, feel bloated and unwieldy, but for my money El Cid is the best from the period apart from David Lean’s Lawrence of Arabia (1962). Just for the intense jousting sequences alone the film is worth seeing. The film has aged incredibly well and remains an impressive reminder of the high water mark of a type of filmmaking that is no longer economically feasible without the assistance of CGI. Mann followed up El Cid with The Fall of the Roman Empire a film I am embarrassed to admit that I have never seen. I know Martin Scorsese admires the film quite a bit but as I was preparing this post I could not find a copy of the movie online that preserves the original aspect ratio. If anyone knows where I can find a pristine copy, please let me know.

* * *

Anthony Mann’s career was sadly cut short by a heart attack in 1967 while filming the cold war spy thriller A Dandy in Aspic (1968). The film would later be finished by the star of the movie, Laurence Harvey. One of the only resources available on the career of Anthony Mann is a British documentary about that production that I’m including below.

https://youtu.be/ZzJy9hGD2aQ?list=PLsvZpF7ouda7fQR1zJf3CGiuh0Ok0R4pF

I guess I’m breaking my promise not to obsess over Anthony Mann’s life by including this documentary but watching Mann in this interview underlines what a natural born storyteller he was and how he understood on a primal level the importance of telling his stories visually. I count myself fortunate that I still have so many Anthony Mann movies left to see, some of which are considered to be among his best: Bend of the River (1952), The Last Frontier (1955), Men in War (1957) , Cimarron (1960) & The Fall of the Roman Empire (1964). My one major takeaway from Mann’s movies is his deep understanding of the flexibility of the western genre. He knew that the savage, untamed American West was the perfect setting for any kind of story imaginable from Greek tragedy, to a contemporary adaptation of King Lear (an ambition he never pulled off) or any dark tale of morally compromised men facing impossible decisions. I’m now very happy to include Mann’s name among the ranks of my favorite directors. Perhaps Mann was more subtle than some of the other more colorful characters on my list in terms of asserting his personality over his work, but the consistency of the power of his storytelling impresses me more and more with each film I see. So while I might be a few decades late to the party in appreciating his films for what they are, I am thankful that I finally managed to open my eyes to the great work of Anthony Mann.

I am one of the Co-Hosts of Wrong Reel and you can find our content here:

Join the Conversation on Twitter

Essential Films by Anthony Mann: