Writer-director Paul Thomas Anderson makes me think many things. Some of those things are funny, some are sexy, some are stupid and dirty and perverted. He makes me think and think. And he makes me envious. Makes me violent, happy, angsty, anxious, tormented, repressed, and gay. It’s all there. Layer after layer, peel it back and discover: there’s more to peel. That’s his way.

And who knows if he does it on purpose or not, and if he means the many barbs he’s thrown at the American mindset (but like…yeah…duhhhhh! of course he does, and he does it so damn well!) PTA endows his movies with such loaded questions that you have no clue what’s gonna come unraveled from one viewing to the next.

So here it is—so I can finally try and line my ducks in a row—some of my thoughts on Mr. Paul Thomas Anderson:

PTA Inquiry No. 1:

Inherent Vice. How’re people gonna take it?

Not too well, I’m afraid.

It’s unfortunate to say, but I fear that Inherent Vice may prove to be PTA’s biggest flop. It’s nearly three hours long, incoherent, and full of long and ponderous shots, many of which are conversations—back and forths in the manner of a Jarmusch-y slow burn—between two to three people as the camera slowly—but oh-so surely—zooms in on the paranoia, the greed, the urgency, the stoner-like focus of a private investigator savvier than anyone gives him credit for. It’s muddled, it’s skinny in weight and “meaningfulness,” it barely talks of “America” and the obvious, more on-the-nose overtures of identity, masculinity, depravity, and what have you. all the themes and motifs PTA’s come to rely on, and—if you’ll allow me to ramble for a moment—it’s even funnier, sillier, and more frivolous than PTA’s unsung minor masterpiecePunch-Drunk Love. To boot: it’s everything that There Will Be Blood and The Master are not. And in case you’re wondering what those two films are, well: they’re two very, very serious examples of the deconstruction of American archetypes and ideologies that’re fully realized through heavy brood and atmosphere, as well as beautifully-rendered portraits of The Great American Disease: Self-Induced Loneliness.

Yeah…Inherent Vice is certainly none of that.

The same thing happened when Punch-Drunk Love was released back in ‘02. It had the unfortunate position of following PTA’s trajectory on the heels of what were then considered the young auteur’s “masterpieces”: Boogie Nights andMagnolia. They were huge ensembles, unyielding in scope, gravitas, and length in reach. Incidentally, they were also self-indulgent—Magnolia certainly was—Biblical, and touched with the visceral, “knife in the gut” verve and confidence of Scorsese’s best work. They spoke of the American family, the stagnant transience of a Californian’s life, the pursuit of touch, love, and sensuality, and the necessity of big cocks and glamorous self-images. Very American stuff. Very universal stuff.

And then came out Punch-Drunk Love. Unlike PTA’s first several pictures it ran under two hours, starred Adam Sandler and Emily Watson—the unlikeliest of pairings—and followed, for the most part, only one character as he navigates the mores of love and loneliness. A sweet film with a very dark but endearing undercurrent of Romance—in the oldest sense of the word, not whatever it’s been appropriated into now. Punch-Drunk Love was a curveball that no one dared to catch.

It wasn’t what the people wanted. There wasn’t a contingency of people out there clamoring for an Adam Sandler art house flick, nor was there anyone tugging on Paul Thomas Anderson’s shirt for a comedy. So, you had the Sandler fans hollering how the movie was nothing like the meticulous brilliance of Little Nicky, and then, you had Anderson “fans” incapable of understanding why in the fuck Anderson would ever think of soiling his reputation with such a crass and over-the-top performer as Sandler.

At this point, upon the film’s release, three years have passed since Anderson’s one-two punch of twitchy, jerky, dollied masterpieces. Three years of conjecture and stoked hope, talk of the Second Coming of Cinema, how he would continue to deliver these sprawling ensemble pieces that went after the American consciousness. People weren’t expecting to get what’s ostensibly a deliriously demented romcom. A romcom made by Paul Thomas Anderson. A romcom inherently marked by its creator’s eye and sense of pacing and thematic hooks.

After all, other than style and music, as well as choice of casting (Phillip Seymour Hoffman is the only Anderson regular to roll over from his first three efforts—ah-hem! Sydney/Hard Eight, no worries, I remember you and your troubled shoot), Punch-Drunk Love still addressed similar themes: how our family effects us, how repression curdles into aggression and violence, and how loneliness and self-preservation conflicts with our ideas of composure and maintaining a certain kind of image for yourself.

Buuuuuuuut! despite all that—despite the fact that a master filmmaker was trying something new and keeping from growing stale or staid, and defying expectations—which, in my opinion, is intrinsically more interesting than a reiteration of a variation—Punch-Drunk Love came, went, and disappointed.

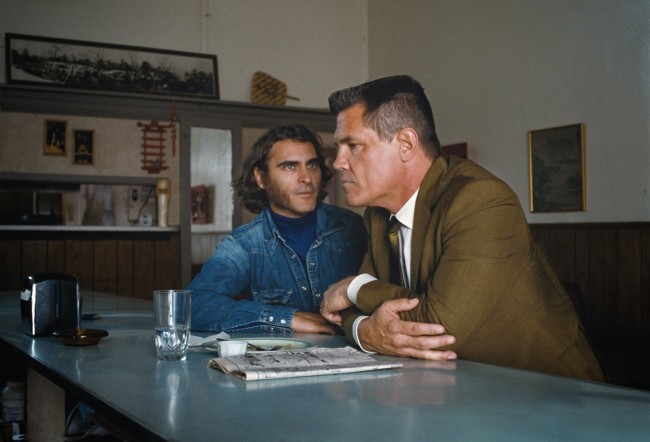

I guarantee it: the same’s gonna happen for Inherent Vice. There’s no getting around the fact that people have—for some reason—fixed PTA in their heads as a very specific kind of director, that he’s only interested in the severe, the pitiful, the hapless who spend their lives at the bottom of America’s metaphorical and moral septic tank. People don’t want romance from Anderson, they don’t want funny—even though he does both insanely well, which he proved in Boogie Nights and Punch-Drunk Love. The man is capable of humanity, unlike some of his peers—I’m looking at you, Coens, Fincher, Soderbergh, and so on and so on—and that’s exactly what he brings to the table between Doc (Joaquin Phoenix) and Shasta (Katherine Waterston) and their relationship—the lead and his girl in Inherent Vice. Their romance is the film’s main through line. At the end of it, it’s his adoration for her that motivates Doc to follow the thread of this particular mystery, that and his obsessive need to see a certain character make it back home to his wife and kid, even if it means giving up the chance at a nice little pot of money.

And yeah, sure, okay, on paper Daniel Plainview and Lancaster Dodd and Freddie Quell are “terrible people,” but—and I truly mean this, but in a very cosmic way, unattached to any and all human-constructed beliefs or rules on morality—they really aren’t. They’re just perfectly shaded beings walking around, bumping up on others, aiming to satisfy their private motivations. They’re too intimately rendered for PTA to simply damn them. Daniel does—from time to time—exhibit patriarchal warmth towards his boy, especially at the start of the film (and most of that manifests itself from the loneliness one must contend with while working the desolate deserts of the western frontier), and Dodd and Quell, as selfish as they are, are awfully selfless and giving with one another, and forthright, too, about their lives, their troubles; they wrestle, they serenade each other, they share cigarettes as post-coitus lovers do. They love, they’re capable of love, but these notions, of human connection, are sometimes lost in the onslaught of all else that’s going on PTA’s films, because they are so fraught with heavier and loftier goals (which will be discussed in future essays, for sure).

Listen, all I’m trying to say is that it’s unfair to harangue and abandon a director for trying something new. We tell our studio directors—tired, hackneyed, recyclable dudes like Bay—that they should let up and try something new, but when it comes to our true visionaries, like Anderson, we want them to stay exactly where they are. We want to suffocate them, stunt them from growing any further—like handing a kid a two-pound bag of coffee, supplemented by a Duty Free thing of Marlboros—we want them to show us the magic trick again and again and again. Because we know it’s great, and we can’t possibly imagine them doing something just as great again, not with a different formula. And it’s because we do lack the imagination of The Visionary that we can’t possibly fathom Anderson being “great” and “masterful” unless he’s cranking what we’ve come to perceive as The Great American film. It’s impossible for us to think that a small movie with modest aims can be considered masterful, too.

And the thing that disappoints me most—without getting too much into it, since you’ve probably caught on by now that I seriously loved Inherent Vice, for its heart, its questionable sense of humor, its unusual characters, its irreverent dismissal of plot and/or cohesiveness, and—most importantly—it’s sense of freedom and unexpected delight—is that it’s a film that touches upon something that not too many movies or directors have the stones to discuss anymore: the idea of optimism. Hipsters and all other irony-swinging dicks hate sentimentality in their films, and—when it comes down to it—this is a film opting for optimism, for the idea of helping your neighbors—ideas that people consider treacly and sweet now. But I bought it. I didn’t need the grit, I didn’t need the unrealistic mountain of cynicism that spoils so many movies today. I didn’t—and don’t—need affectation. And Inherent Vice is light on affectation. It asks us to think about notions that have disappeared from our vocabulary, our lexicon, our public consciousness: our notions of Romance, of hope.

It’s easy to simmer in irony and self-pitying cynicism—what’s difficult is getting over yourself enough to see the potential for social awareness and growth that exists all around us, ready for the plucking, ready to be fully realized into something more concrete, to transform from awareness to action.

So yeah, I hope it doesn’t flop, but we’ll have to wait and see. I don’t think our black, nasty hearts are quite ready for Inherent Vice. But, then again, that just may be my jaded hipster heart talking. Maybe it’s time I go ahead and get over myself, make room for hope.

What else can one do?