By James Hancock July 20th, 2015

In 1918, Dr. John Romulus Brinkley achieved notoriety with his claims of restoring male virility by transplanting and grafting the testicular glands of goats into his patients. Dr. Brinkley was fond of operating while intoxicated, his patients often suffered from severe infections or died outright, and usually the goats balls would simply dissolve in the bodies of his patients with no impact whatsoever on their erectile dysfunction. The fact that many patients lined up for this process tells us more than I care to admit about my own gender. I would likely have lived out the rest of my days in blissful ignorance of this horrid procedure if not for my interest in Canadian filmmaker Guy Maddin. I recently watched an interview with Maddin from the 2015 Sundance Film Festival (see below, starting at 21:32) where he used the expression ‘goat gland’ to describe a type of movie unique to the late 20s. When Hollywood started making the transition to sound, audiences embraced the new format so quickly that many silent films were put on a shelf by studios to rot. Some of these films were eventually dusted off and had scenes with dialogue and/or musical numbers inserted into the narrative in order to market them as talkies. These hybrids were referred to by the industry as ‘goat glands’ with 1929 condescendingly described as ‘the year of the goat gland’. Guy Maddin has never understood why this would be considered a criticism. From his perspective, many of these movies benefit from the best qualities of both the silent era and the early talkie era. For the last 30 years Guy Maddin has been using this hybrid approach as a source of inspiration for a body of work that I consider to be one of the most distinctive and entertaining in the world today.

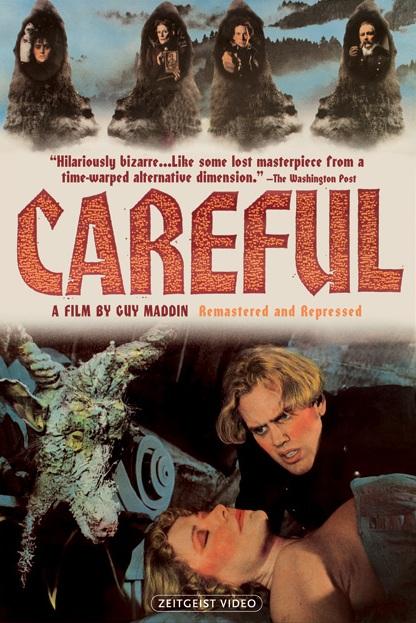

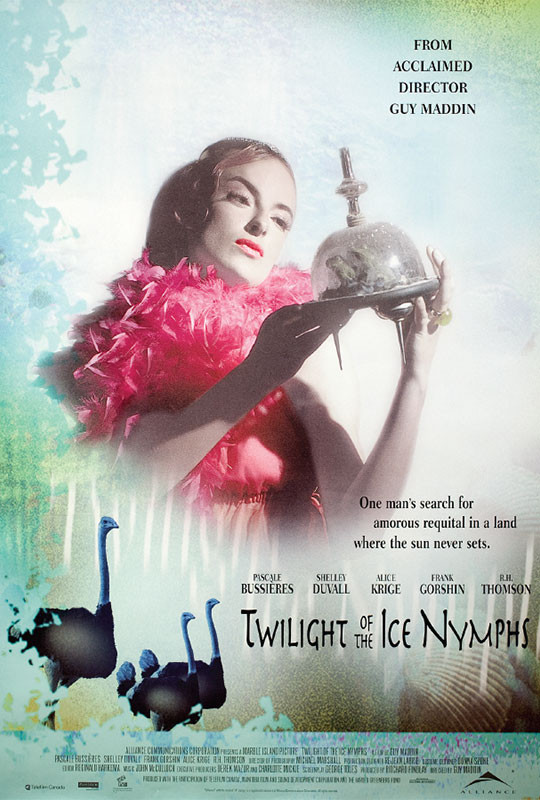

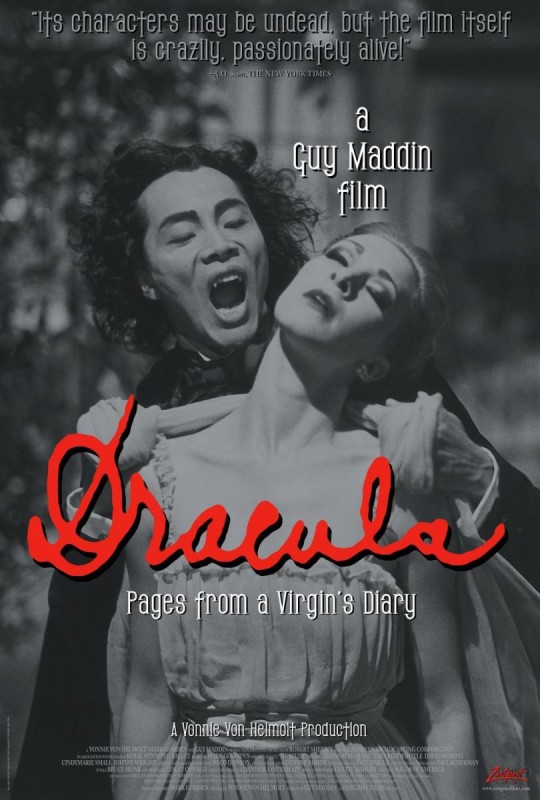

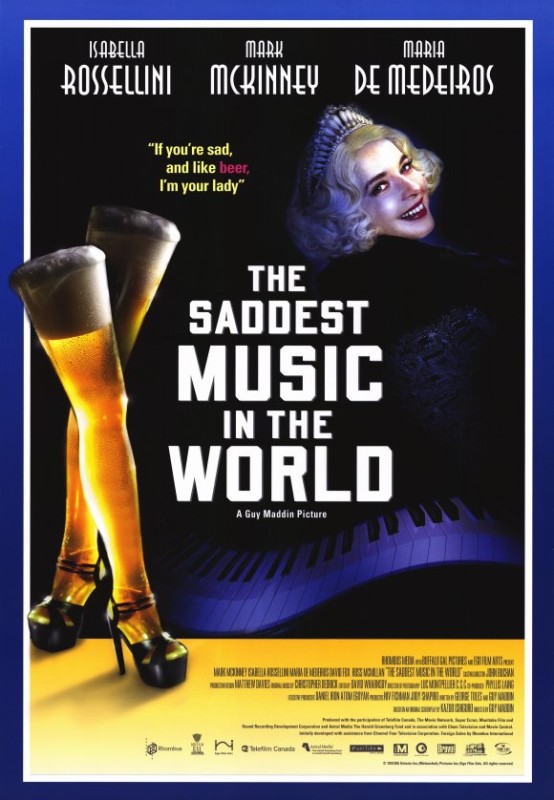

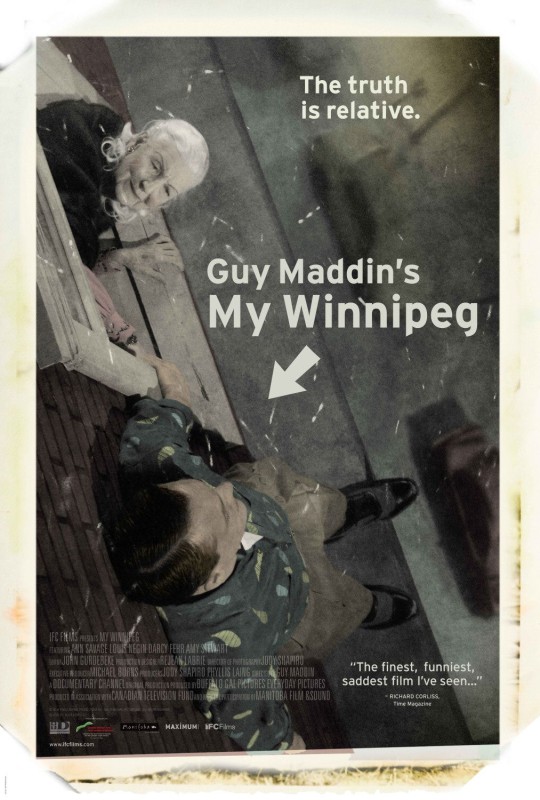

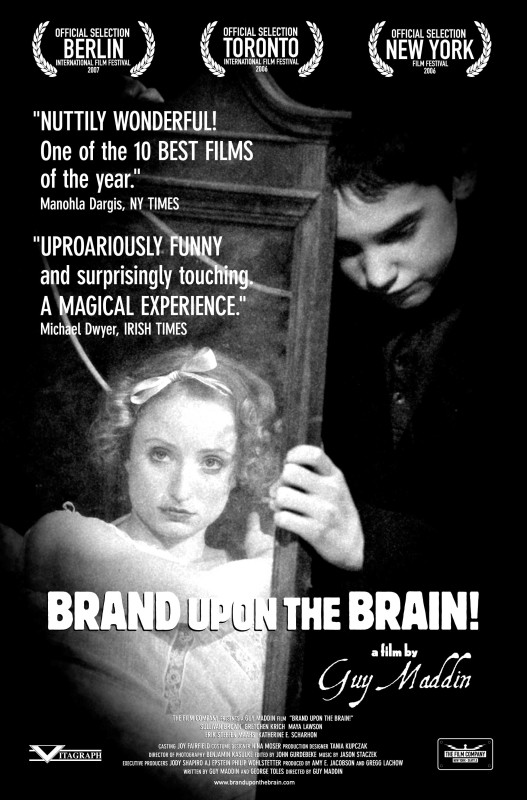

If you’re unfamiliar with Guy Maddin’s work, you’re not alone. With the kinds of movies Maddin makes, he will never dominate an opening weekend. Nor will his films likely win any Oscars in that most of his movies would cause a high percentage of the blue-haired members of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences to die from shock. With his fetishization of so many subjects including film history, incest, melodrama, artifice, sleepwalking, hair salons, German mountain films, homosexuality, ice hockey and of course his remote, icy home town of Winnipeg, the barriers of entry into his work can intimidating at first for the uninitiated. That said, Maddin has been quietly building an audience over the years, leading to the Criterion Collection’s release of some of Maddin’s best films Brand Upon the Brain! (2006) and My Winnipeg (2007). It is impossible to be indifferent to his work and if one of his movies manages to gets its hooks into you, you’ll have no choice but to plow through as much of his filmography as you can get your hands on. The only way I can describe the style of his movies is to create a hypothetical scenario where time and the development of new technology stopped in the year 1929 but cinema as an art form continued to evolve and transform by leaps and bounds. Technically this description is completely unfair in that Guy Maddin has always embraced new technology as it emerges but he has always used these developments to reinforce the illusions he creates in the style of a proper goat gland. Like the best films of that period from Soviet Cinema and German Expressionism, Maddin’s films are incredibly dynamic visually and nearly always intensely melodramatic. In discussing melodrama, Maddin has stated, ‘Good melodrama is the truth uninhibited, not exaggerated, but uninhibited. When you exaggerate the truth you make it untrue, but when you uninhibit it the way fairy tales do, you make the truth more apparent.’ To help people with their first exposure to his work, Maddin has also described his work as ‘opera without singing’. To give you an idea of what I’m talking about here is his short film The Heart of the World (2000) which is one of my favorite movies I’ve ever seen. This is a movie that somehow manages simultaneously to tip its hat to the great silent films of the past while exploding cinema as an art form and reinventing it’s grammar from the ground up.

As if Maddin were not busy enough (between his short films and features he has directed over 50 movies), he has also carved out a niche as one of the best writers about film and film history that I’ve ever encountered. Guy Maddin likely forgets more about film history in a single day than any of us will ever learn. But even more impressive than his encyclopedic knowledge of ancient cinema is the style and humor he brings to his essays on film. I first discovered his work on this front in the book From the Atelier Tovar: Selected Writings of Guy Maddin. Criterion Collection also routinely asks him to chime in on a variety of topics from the silent films of Josef von Sternberg to Billy Wilder’s Ace in the Hole. So many cinephiles (myself included) unintentionally make the study of film history feel like an absolute chore where we place the great films of the past on such a high pedestal that we drain all the fun out of discussing them. Maddin, on the other hand, makes watching old movies feel as forbidden and exciting as attending a clandestine burlesque show where Marlene Dietrich, Joan Crawford and Greta Garbo are the feature attractions. There is a kinky, taboo-breaking allure to the way he explores the cinema of the past and every stuffy, self-important film fanatic out there could benefit from taking a page out of Guy Maddin’s book. Check out the video below for Guy Maddin’s greedy rampage through the DVDs and Blu-Rays offered by the Criterion Collection.

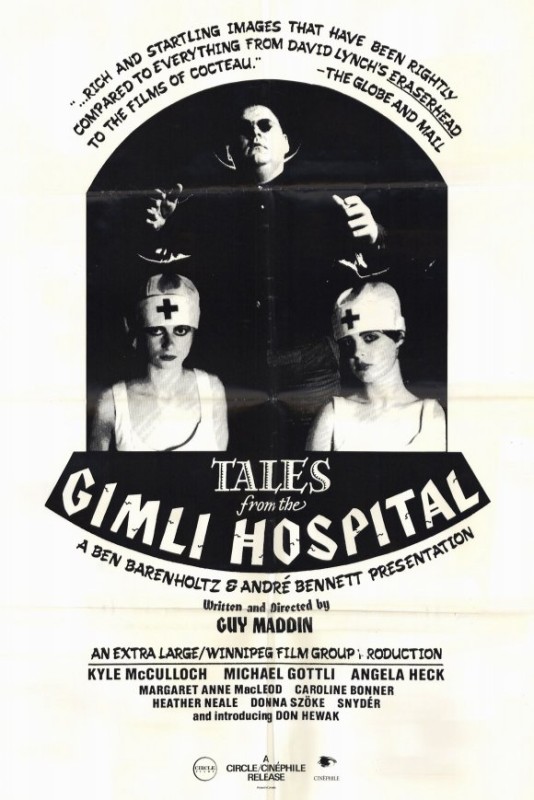

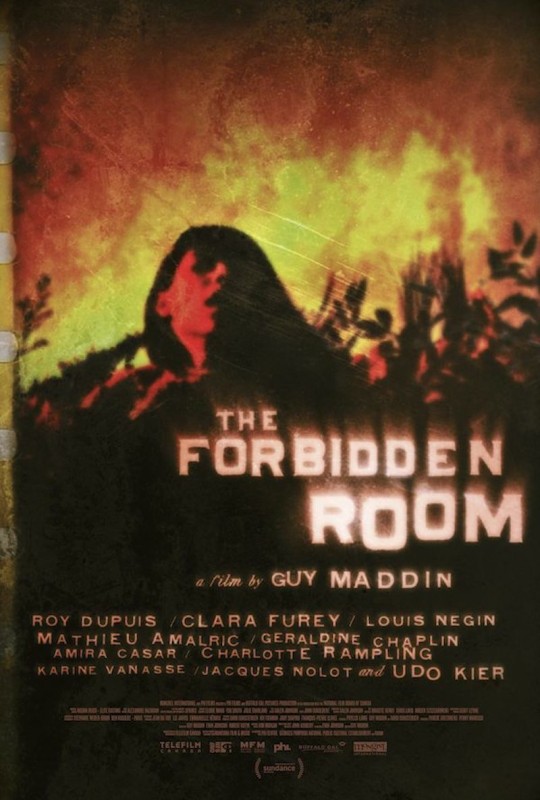

For reasons I can’t properly articulate, there is something about the look and feel of films from the late 20s/early 30s that perfectly captures everything I love about movies. The opening credits alone to some of these movies such as Little Caesar (1931) and The Public Enemy (1931) make me feel like I’m pulling up a chair next to a warm fire. So when I first saw Guy Maddin’s Tales from the Gimli Hospital (1988) and recognized how in the films’s opening titles Maddin was combining the music and style from those two gangster classics and creating something entirely new, I understood immediately that Maddin is a filmmaker who is 100% speaking my language. He’s one of the few filmmakers alive where one frame from any of his films is immediately identifiable as his work. Like the two greats Vons of cinema, Erich von Stroheim & Josef von Sternberg, Maddin’s films are laden with the kind of decadent imagery and rich shadow play that has not been seen in Hollywood for many decades. His love of old movies, in particular movies that have been lost irretrievably to the ravages of time, is such that that he often produces films using the same titles as these lost films leading to projects like his latest feature film The Forbidden Room which was originally an Allan Dwan film from 1914. I’m thankful that I still have many of his movies left to see including The Forbidden Room which has not yet been released in the United States. He also has a new film he’s cooking up, probably at some black mass with F. W. Murnau’s headless ghost, called Seances starring Charlotte Rampling, Udo Kier and Geraldine Chaplin. I couldn’t be happier for him. He deserves a reputation on par with David Lynch but the sheer otherworldliness of his films has kept many audience members at bay. But if you are of a stout heart, I urge you to check out his work. And if you consider yourself a film lover, or more importantly have a taste for exotic films about barely contained perverted urges with a dash of childlike wonder and innocence, Guy Maddin’s movies are absolutely required viewing. I obsess over the great heyday of Hollywood’s most sinful and artistically adventurous period, the year of the goat gland, and if you do as well on any level Guy Maddin’s films will keep you deliriously entertained and in a dreamlike state of bliss every second they are projected in front of your eyes.

I am one of the Co-Hosts of Wrong Reel and you can find our content here:

Join the Conversation on Twitter

Guy Maddin’s Feature Films:

‘Tales from the Gimli Hospital’ (1989)

‘Archangel’ (1990)

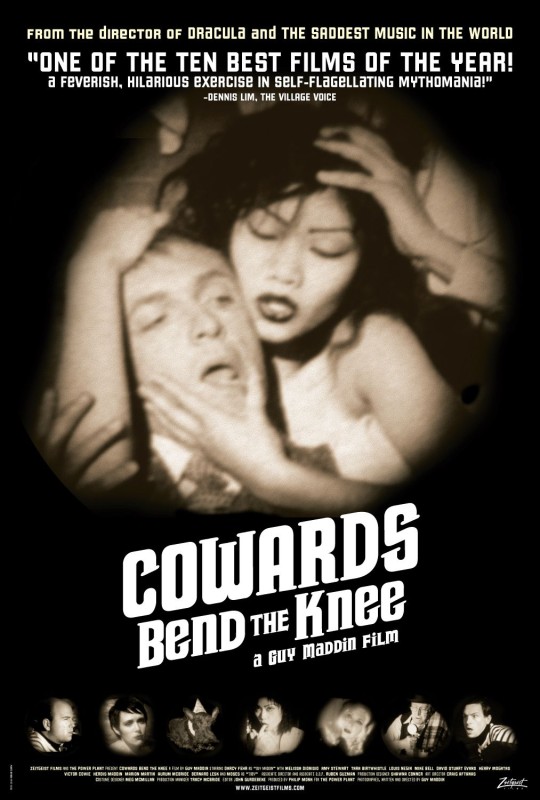

‘Cowards Bend the Knee or The Blue Hands’ (2003)

‘Brand Upon the Brain! A Remembrance in 12 Chapters’ (2006)

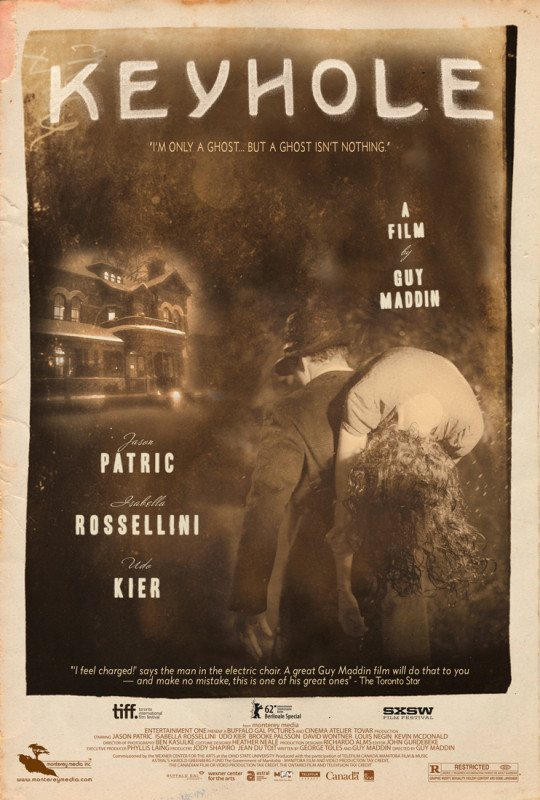

‘Keyhole’ (2011)

‘The Forbidden Room’ (2015)