By James Hancock September 23rd, 2015

Fritz Lang is one of a handful of directors from the silent era whose work is recognizable even by those who couldn’t care less about film history. If someone has never seen Metropolis (1927), chances are high that person would still recognize imagery from the film, or even more likely, has seen those later sci-fi classics it inspired such as Star Wars and Blade Runner. But for film connoisseurs, Fritz Lang is much more than just the man who gave us Metropolis. Lang is one of the giants of cinema, a director of singular vision responsible for a body of work that stretches out over several decades in spite of having to abandon his career at its peak in the early 1930s in order to escape the rising influence of the Nazi party in Germany. When Lang’s film The Testament of Dr. Mabuse (1933) outraged the Nazi party, Lang was called to a meeting with Joseph Goebbels. While Goebbels made it clear that The Testament of Dr. Mabuse would be banned from cinemas, Goebbels surprised Lang telling him that Hitler admired his films and that they wished Fritz Lang to be in charge of all German film production at UFA. In the interview below with William Friedkin, Lang recounts how he pretended to be flattered but cautioned Goebbels about his Jewish heritage. Goebbels replied that it was his job to decide who was an Aryan. Desperate to get out of the meeting without getting arrested, Lang promised to think over the proposal. Soon thereafter Lang left Germany for France, leaving behind his wife and chief collaborator Thea von Harbou who was loyal to the Nazi party. Lang made one film in France, Liliom (1934), before finally making the move to Hollywood where he would direct more than twenty films. Lang’s Hollywood films do not receive nearly the attention they deserve. He brought a bleak, unsentimental pessimism to Hollywood filmmaking that had never been seen before in American film, a perspective that keeps his films fresh and modern far moreso than some of the more respectable films of that period. Long before the French coined the phrase film noir, Fritz Lang’s American films visually and thematically explored the inherent darkness in human beings creating an unforgettable cinematic world of conspiracy, mistrust and paranoia that in many ways is just as fascinating if not more so than his more famous work in Germany.

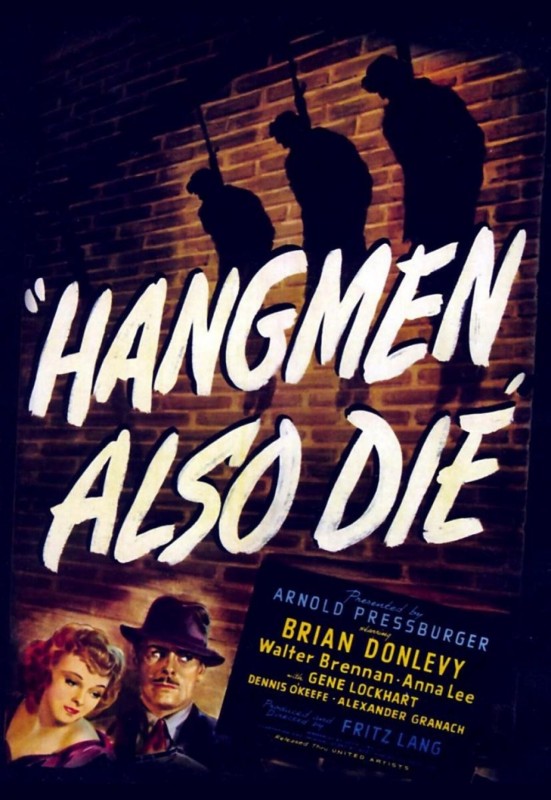

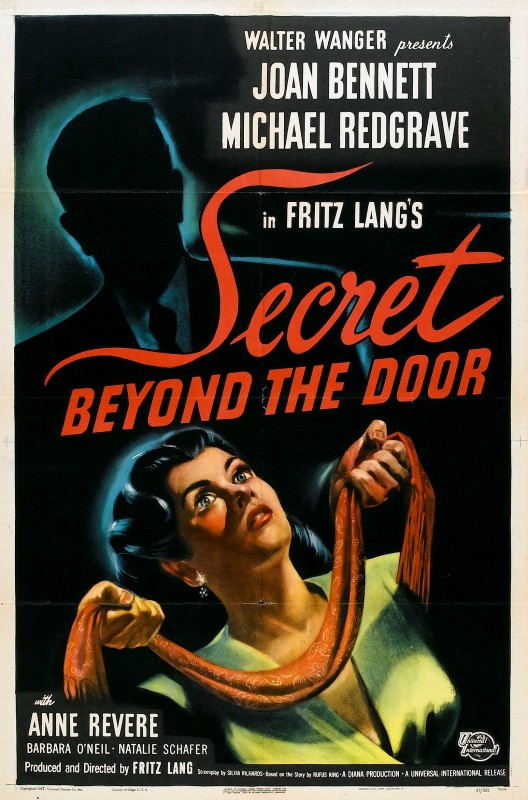

Of all the European immigrants that came to Hollywood in the Thirties and Forties, save perhaps Alfred Hitchcock, Fritz Lang most successfully adapted to the Hollywood movie factory. Lang often worked with smaller budgets where he was subjected to less studio oversight giving him countless opportunities to smuggle controversial content and ideas into his films. Lang’s world is one of moral ambiguity where there is no such thing as good and evil, only pain and guilt, real or imagined. No matter what genre he was working with, from westerns to spy films to thrillers, no director of that period did more to indict the callousness of society and the dangers of mob justice. He never forgot the career he was forced to leave behind in Germany and he applied this anger to a variety of anti-Nazi propaganda films, a sub-genre that he practically built singlehandedly (Hangmen Also Die!, Ministry of Fear, Cloak and Dagger). He went so far as to declare war brazenly on Hitler in Man Hunt (1941) long before the United States officially entered the war. All societal commentary aside, Lang was a master of tightly constructed plot-driven stories with legitimate twists and surprises that are incredibly effective to this day. Some claim he was cruel on his movie sets and difficult to work but it seems to me that this reputation is undeserved. While many complained about his manner, it is worth noting that many actors and actresses worked with him time and time again including but not limited to Henry Fonda, Sylvia Sidney, Joan Bennett, Edward G. Robinson and Gloria Grahame. Sadly, Lang in Hollywood never achieved the commercial success he had enjoyed in Germany and the prevailing wisdom at the time was that he was washed up. For years, Lang saw his reputation in the industry unfairly thought of as one in a perpetual state of decline. But in the years after he stopped making films, thankfully his work was rediscovered and reassessed by critics and filmmakers like Peter Bogdanovich and Jean-Luc Godard (who cast Lang as himself in Contempt). What’s clear now is that Lang was never bankrupt of ideas or talent. He was only guilty of forcing audiences to confront certain uncomfortable truths about life from which most people tend to recoil.

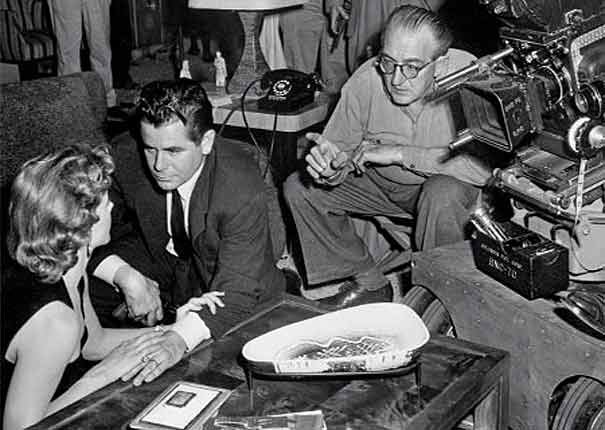

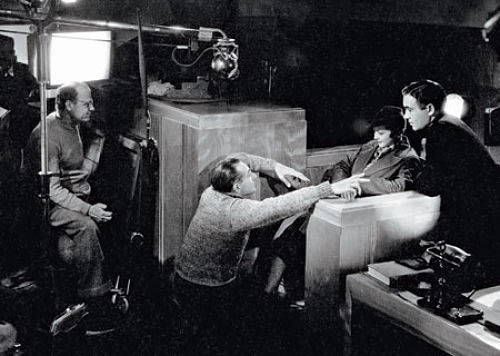

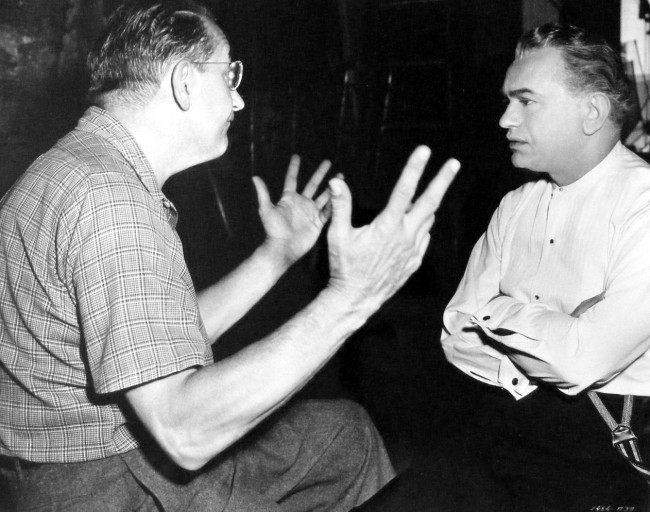

Joan Bennett at work w/ Fritz Lang on one of his best films, ‘Scarlet Street’.

Recently I had the extraordinary opportunity to see a fully restored print of Fritz Lang’s mythological epic Die Nibelungen (1924) at the Telluride Film Festival and I decided it was time for me go deep into Fritz Lang’s work, in particular his American films, a period I had largely neglected apart from a few essential classics. I initially planned just to dip my toes in the water but once I got started I found it very difficult to stop. I spent weeks digging through this period watching many of Lang’s American films for the first time and some of his better known films for a second time. By the time I had come up for air I had seen Fury, You Only Live Once, You and Me, The Return of Frank James, Western Union, Man Hunt, Hangmen Also Die!, Ministry of Fear, The Woman in the Window, Scarlet Street, Cloak and Dagger, Secret Beyond the Door, House by the River, American Guerrilla in the Philippines, Rancho Notorious, Clash by Night, The Blue Gardenia, The Big Heat, While the City Sleeps, and Beyond a Reasonable Doubt. I had no luck unearthing Moonfleet and the only way I could find Human Desire was by ordering a large box set of DVDs which I declined to do. There are also two films where he worked uncredited, Confirm or Deny and Moontide, only to be replaced by director Archie Mayo so I decided to take a pass on those as well. But I have seen enough now where I feel confident in creating a Top 10 list of my favorite movies Fritz Lang directed during his time working in Hollywood, a filmography that makes him one of the most impressive directors of that era even if one were to ignore the many brilliant films he had already made prior to his arrival in the United States (Destiny, Dr. Mabuse: The Gambler, Die Nibelungen, Metropolis, M).

Fritz Lang’s Top 10 American Films

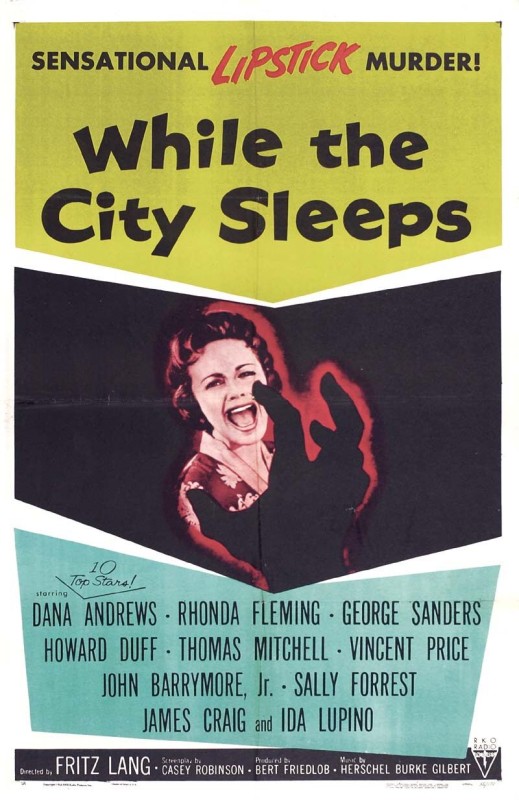

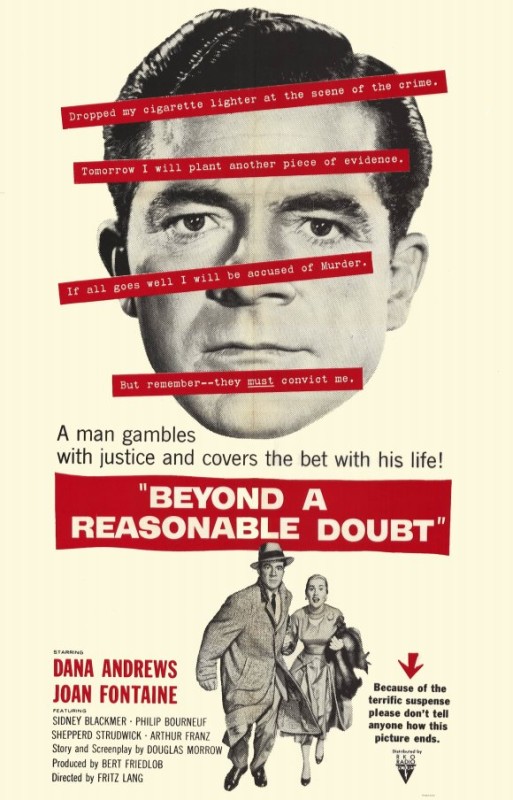

10. Beyond a Reasonable Doubt (1956)

The last in Lang’s ‘Newspaper Trilogy’, a trilogy that also includes Blue Gardenia and While the City Sleeps, this film is perhaps the most pessimistic film Lang ever made. In an effort to show the injustices of capital punishment, a writer played by Dana Andrews decides to frame himself for a murder he did not commit. He places all the evidence of his plan in the hands of the father of his fiancée but leaves his bride-to-be (played by Joan Fontaine) out of the conspiracy. The sick pleasure of watching this movie is knowing full well that Andrews is placing a noose around his own neck. This is a Fritz Lang movie after all. When the future father-in-law is killed in a car wreck, Andrews realizes what a terrible mistake he has made as he desperately tries to prove his own innocence before he is put to death.

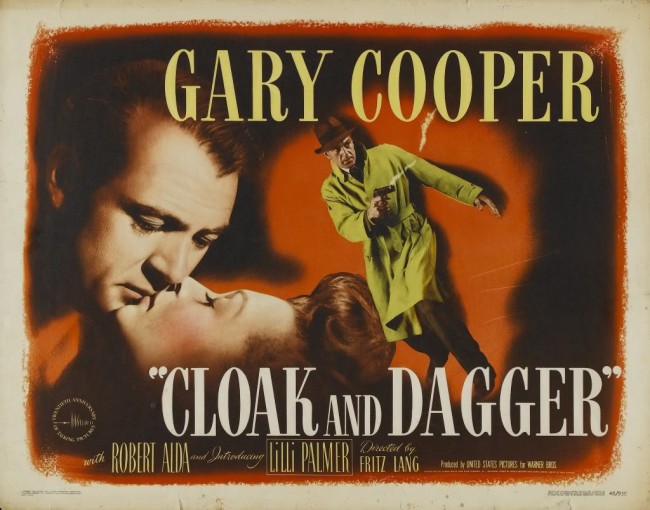

9. Cloak and Dagger (1946)

Inspired by the work of the OSS during WWII, Cloak and Dagger stars Gary Cooper as a scientist who becomes an unlikely spy trying to prevent the Nazis from gaining the secret to building an atomic bomb. In addition to being a classic espionage thriller starring one of the best leading men from the Golden Age of Hollywood, the film surprisingly features some of the most intense action sequences I’ve seen from that period. Fans of MMA will immediately recognize some of the grappling techniques employed by Cooper including what might be the earliest example of the kimura caught on film.

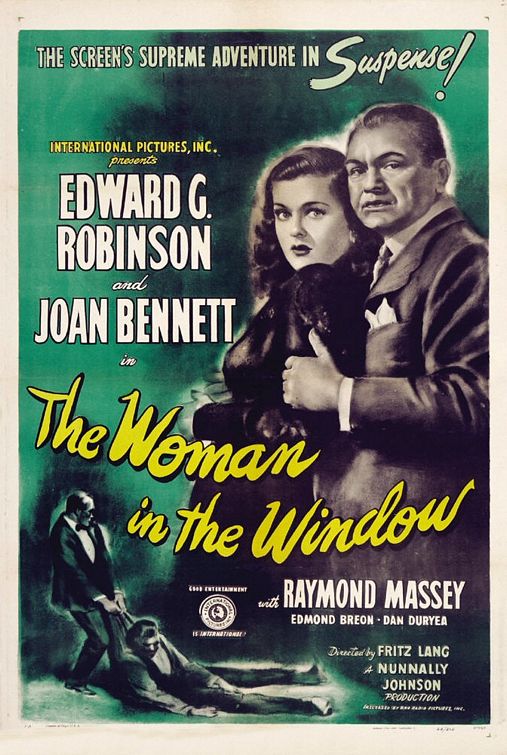

8. The Woman in the Window (1944)

Joan Bennett worked with Fritz Lang three times and no actress did more to bring out the erotic side of Lang’s movies. I have no idea how this movie got past the censors but there is a lengthy scene where Bennett wears a sheer dress that leaves next to nothing to the imagination. This tale of murder and mayhem is probably the closest thing Lang ever made to a black comedy. Edward G. Robinson plays an aging man who despises what he feels is a weakness of the soul. While his desire for women remains strong, he lacks the courage to do anything about it. But when he takes a chance on Joan Bennett, he soon finds himself in a fight to the death with a jealous guy. All hell breaks loose as Robinson and Bennett try to cover up their crime, a crime that Robinson’s conscience seems determined to confess at every available opportunity. What we have with The Woman in the Window is a classic Lang scenario where the protagonist seems determined, in spite of himself, to end up in the electric chair, a theme that would be repeated throughout Lang’s career.

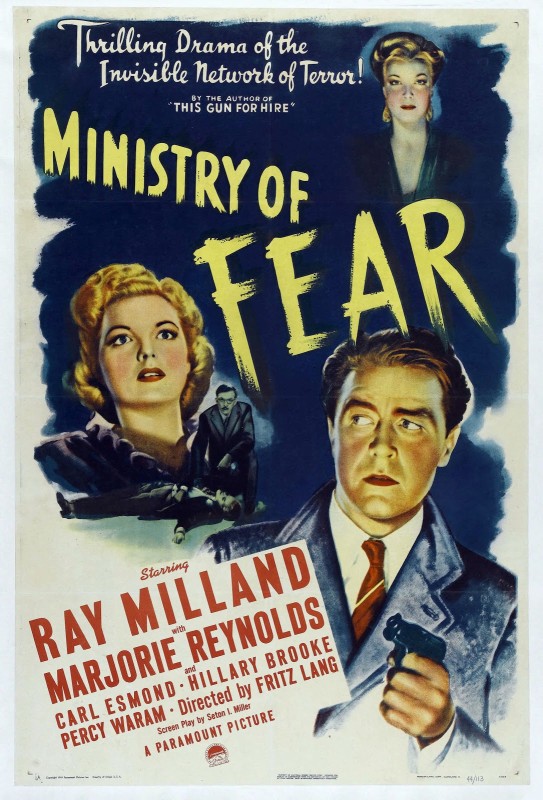

7. Ministry of Fear (1944)

Of all Lang’s WWII films, Ministry of Fear is arguably the best. Based on the novel by Graham Greene, the story focuses on Stephen Neale (played by Ray Milland) who after being released from a mental asylum accidentally stumbles into a Nazi plot where he finds himself framed for murder. Featuring some of the best visual flourishes and shadow play of Lang’s work, Ministry of Fear is a genuinely paranoid thriller worthy of comparisons to the suspense films of Alfred Hitchcock.

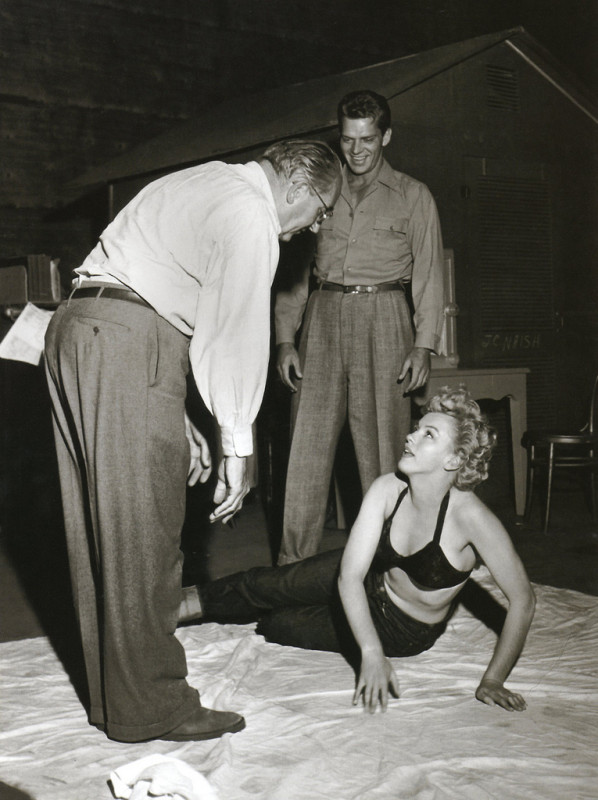

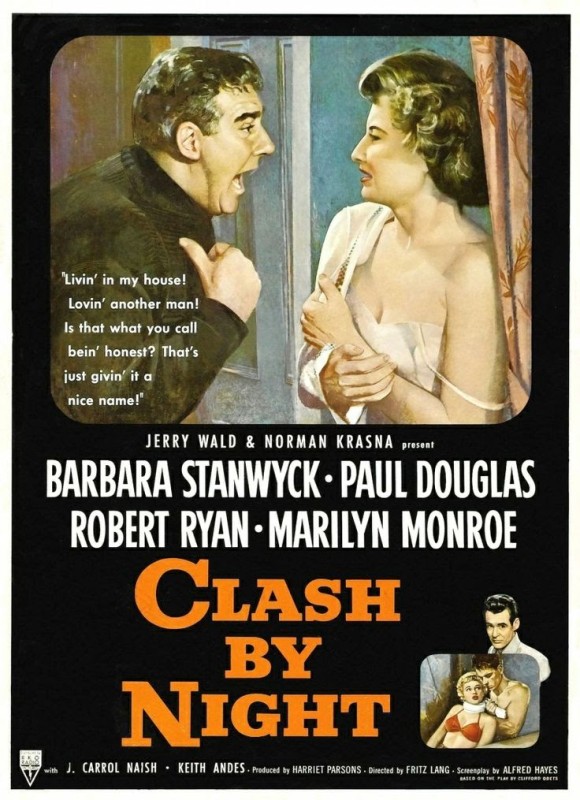

6. Clash by Night (1952)

Marilyn Monroe might be better known for her light-hearted work with Billy Wilder, but Fritz Lang, in my opinion, gave us the best performance of Marilyn Monroe’s career. Monroe is not even the star of the movie but after watching Clash by Night, she is all I can think about. There’s something incredibly honest, almost confessional, about her portrayal of a character who enjoys feeling a man’s hands on her, even in violence, if only to give that man a taste of it himself. Based on a play by Clifford Odets, Clash by Night is a down and dirty melodrama about people who seem to fall in and out of bed with one another even when these affairs ultimately prove destructive. Barbara Stanwyck and Robert Ryan also deliver fine performances. What this film lacks in actual violence compared to other Lang films, it more than makes it for it with emotional turmoil.

5. The Big Heat (1953)

Perhaps the most popular film today from Lang’s American period, The Big Heat is an essential film noir and one of the most brutal films of the 1950s. Glenn Ford plays an honest cop in a corrupt city ruled by crime. When he tries to do his job, he finds what feels like an entire society out to get him and his family in the most vicious ways imaginable. The film also features a brilliant early role by Lee Marvin and the now notorious scalding hot coffee scenes between him and Gloria Grahame. One of Lang’s most accessible films, The Big Heat is a blast to watch from start to finish.

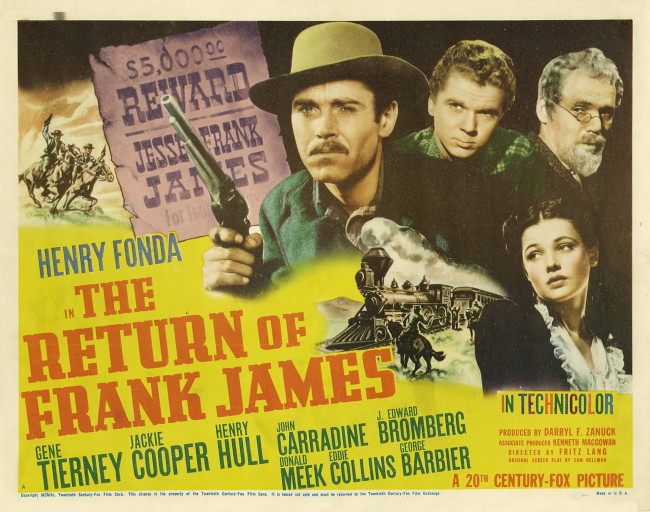

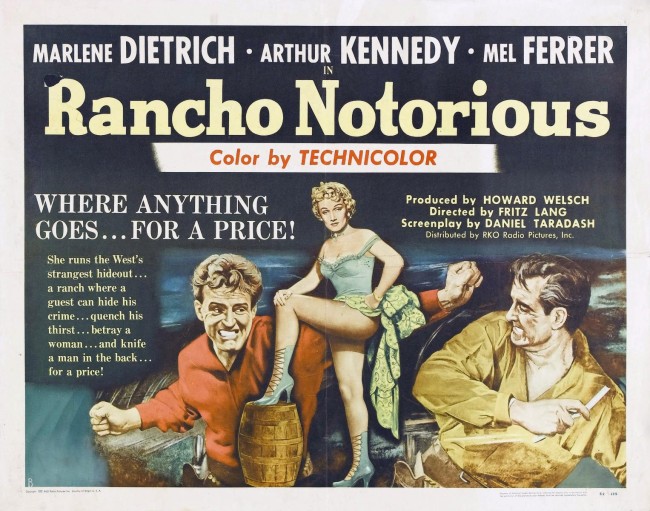

4. Rancho Notorious (1952)

Rancho Notorious has a special place in my heart. It was the first American film by Lang that I saw and I had the unique opportunity to see it in the theater during my first summer working as an intern in Los Angeles in 1997. While few people associate Lang with the western genre, he worked in it periodically with movies such as The Return of Frank James and Western Union. The theme song perfectly expresses the emotions central to Lang’s films with the line, ‘It spins the old, old story of HATE, MURDER AND REVENGE’. If you haven’t seen the movie, you’ll understand the caps after you do. The story features Arthur Kennedy as a man hellbent upon avenging the murder of his fiancée. His pursuit leads to a ranch run by Marlene Dietrich where criminals can find safe haven in exchange for a piece of their profits. What follows is one of my favorite westerns of the 1950s, one that ranks easily alongside other unconventional westerns of period like Nicholas Ray’s Johnny Guitar (1954).

3. You Only Live Once (1937)

In the fine tradition of movies featuring outlaw lovers of the run like Gun Crazy, Pierrot le Fou, Bonnie and Clyde, Badlands and True Romance, we have Fritz Lang’s You Only Live Once starring Henry Fonda and Sylvia Sidney. Fonda plays a reformed outlaw trying to go straight and build an honest life for himself and his wife, but society repeatedly puts out its foot to trip him. Wrongfully accused of a crime he did not commit, Fonda ends up back in jail having lost all faith in the law. By the time he is pardoned for his crimes, it is too late. Fonda no longer trusts anyone, breaks out of jail and ends up killing the one man who had the most faith in his innocence.This is one of Fonda’s best early roles while Sylvia Sidney is always a delight to watch in action. As always through the lens of Lang’s perspective, any old fashioned ideas about truth and justice are completely evaporated by this film.

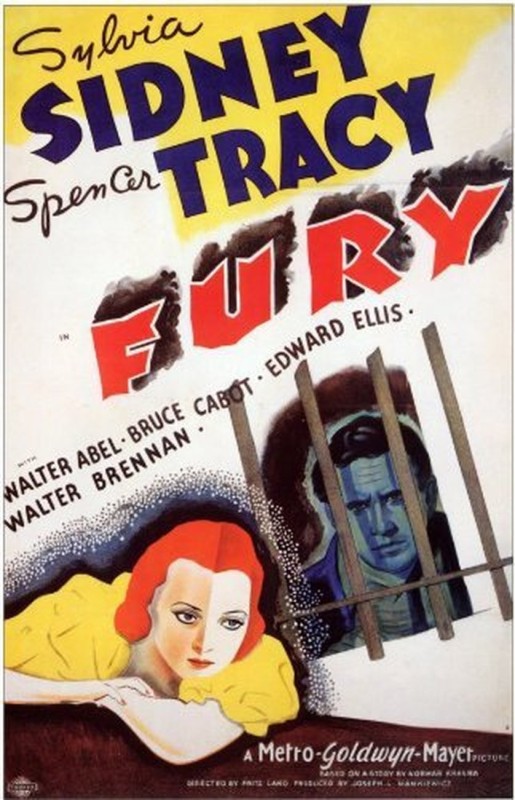

2. Fury (1936)

Fritz Lang announced his arrival in Hollywood with one of the best films he would ever make, the unforgettable Fury. Spencer Tracy was never better than in this story where on the flimsiest evidence imaginable, he finds himself locked in jail in a small town. Drunken thugs decide to take the law into their own hands and storm the jail intending to lynch Tracy only to burn down the building instead. Tracy narrowly escapes with his life but keeps his survival a secret hoping to see his tormentors all put to death for murder. His hate and anger eat away at him like a cancer until he all can think about is revenge. Only Lang could make a movie where halfway through the film, we find ourselves feeling pity for an entire town of people capable of such barbarism. This movie has so many great scenes such as hearing Tracy growl, ‘I could smell myself burning.’ But the moment that tops them all for me is when Lang cuts from a scene of gossiping housewives stirring up hate against Tracy to a scene of chickens clucking and walking around one another in circles. No American film by Lang for me better sums up his feelings about the horrors people are capable of in a mob who then try and pretend as if nothing ever happened.

1. Scarlet Street (1945)

Based on a novel by Georges de La Fouchardière, this story was first adapted into a film by Jean Renoir in 1931 as La Chienne. Both Renoir and Lang’s interpretations are well worth seeing. I don’t want to spoil anything but this film manages the walk the difficult tightrope of being incredibly cynical and emotionally moving all at once. Edward G. Robinson plays an unhappily married middle-aged man who in a rare burst of courage comes to the aid of a beautiful young woman played by Joan Bennett who is being attacked by her boyfriend. Bennett immediately sizes him up as a gullible easy mark and starts trying to squeeze money out of him. Although he has no money to speak of, Robinson is flattered by the attention and plays into the fantasy that he is a successful painter. For those only familiar with Robinson’s powerful roles in movies like Little Caesar, in Scarlet Street viewers will find Robinson absolutely pitiful to watch. At home he is constantly henpecked and emasculated by his gargoyle of a wife and he genuinely thinks he and Bennett may be falling in love. Meanwhile Bennett and her hustler boyfriend are constantly plotting new ways to exploit him even going so far as selling his paintings as if Bennett painted them herself. As can be expected from any Lang film, things do not end well for anyone. Plenty of violence and mayhem ensue before the story closes on one of the most ironic, pessimistic endings I have ever seen.

* * *

So I hope you enjoyed this list and found some good suggestions. This list could just as easily been completely reshuffled and would work equally well in my eyes. Let me know what you think and what your favorite Lang films are. It is only a matter of time before I tackle his German period with the same intensity.

I am one of the Co-Hosts of Wrong Reel and you can find more of our content here:

Join the Conversation on Twitter