FOMO: the fear of missing out. Facebook has certainly played its part in fucking with our heads and making us feel as if we’re busying ourselves with subpar activities, weak parties, shitty dates, with romantic/sexual/platonic partners who can never be enough and should be switched out for cooler, sexier, smarter upgrades. (Shaking my head—or rather: smh). We’re a perpetually unsatisfied culture. Nothing is enough. Nothing will ever be enough. We want to be happy, for our hearts to radiate confidence and contentment. But that would mean buying the first brand of toothpaste you see, rather than surfing through Amazon one hour after the other, switching between reviews of Colgate, Crest, Rembrandt, Gleem, etc., in quixotic search of the finest toothpaste known to man. We read, we inform ourselves, we compare customer ratings—two stars? three stars? four and a half? Which is best? I need the best, because if I get the best, then my teeth will be the best and I will be the best, and being the best means being the happiest, and being the happiest means being the most successful, the most noticeable, the most fuckable! It means being whoever the fuck you want!

Advertising’s clever that way. Those ad men—ah-hem! Mad Men—knew about FOMO before FOMO was even a thing. They understood America’s greatest weakness: it’s fear of being the worst. This is the land of opportunity and growth, where—apparently—you are your only weakness. Even now, everything’s DIY, self made, self-promotion, a pastiche of me me me me me me! We promote everything we like, we wear it like a brand, like an official seal of top doggedness. Everyone has the secret, everyone knows how people work, they know how to crunch the numbers and calculate the most effective, most general way of reaching the broadest audience and magnifying their insecurities.

Don Draper thinks he understands people. As he tells Stephanie—Anna Draper’s niece from several seasons ago—he gets how people work. The man knows all—every creed, color, and sex, he knows how their dials tick—a complex he acquired over the years at his ad agency where the main objective is to tell your customers what they want, and if those customers try and disagree with you then you make sure they feel the burn of a life of mediocrity. Because, as we all know by now, the main point of an ad is to fool consumers into believing that the product is the key to their relief. Not even happiness, but relief. Relief from self-doubt, anxiety—the whole nine yards.

For years now, Don’s been fooling himself into believing that he is the Everyday Man, Joe Six Pack, that he’s the archetypal American male, and for a while there, before reaching millionaire status, he was. He was a poor boy from the Midwest looking for a red, white, and blue lining.

Like everyone else in this country, Don—or rather, Dick—knows the value of reinventing one’s self, a practice that’s becoming more and more difficult to achieve given our compulsive need to document every last detail of our lives. Dick transformed into Don so he could clear his record and make something of himself: the much-fabled Self Made Man.

Don assumed he knew best, that what rumbled through his head rumbled through everyone else’s, too. He cynically believed in everything he peddled. He ran those pitch meetings, sold his ideas, as if he knew what every single nuclear family needed to reach bliss, but without ever considering the fact—or maybe tragically ignoring it—that his family, his wives, his daughter, were all ironically stifled by it, by his vapid attempt to grasp his own fictionalized concept of the American Dream.

That is, until Don met Leonard. One of his many victims.

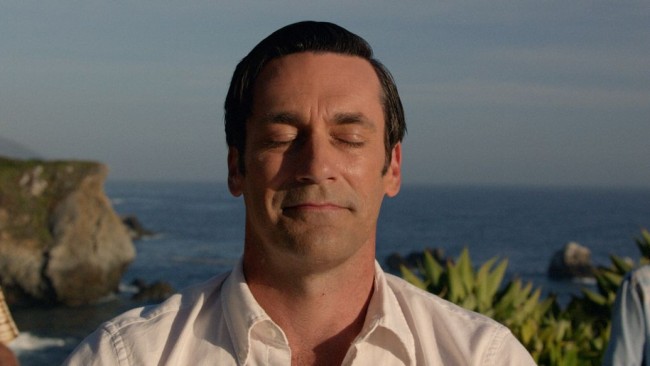

It’s at a self-discovery retreat out on the coastal cliffs of California that Don finally sees how his work has been damaging America and its hungry-to-be-noticed Joes. The actual Average Joe. Or rather: Average Leonard. Leonard takes center stage at group therapy where everyone’s asked to somehow explain how they feel about their pointlessness in life. Leonard is the first participant who isn’t dressed to the gills in hippie-dippie wear. No overalls, no moccasins, no brightly-colored jump suits. A simple man: sweater and slacks, and a bald pate looking for disguise beneath an unconvincing comb over. This is as unordianry as men get. And Leonard knows it. He laments his life, but not really, not passionately. He doesn’t think anyone finds him interesting, not his wife, not his kids—or maybe they do, but he can’t say for sure. He’s a ghost. Invisible to all those around him, even those who rely on him. He shares a dream with the group. A lonely dream. He dreams that he’s been placed aside on a shelf inside a fridge. Whenver the door opens he can see everyone outside, gallivanting, having fun, living life. But then the door closes and the darkness returns. Before long, again, the door opens and a hand reaches in, passes him, and retrives something else behind him. These people stare at him, but not really, they stare right above him. A non-entity. Finishing his dream, Leonard plummets into a gulf of sadness. A wretched display. Heartbreaking. The power of it snaps Don out of his catatonic state, prompting him to stand up and embrace this defeated man, this unimportant man, this commonplace man.

Don sees what he’s done to Leonard. And to everyone else. The havoc he’s wrought, the high expectations he’s set for people. He tried to apply his own financial—and psychological—standings upon millions of other people without realizing: not everyone can be part of the upper middle class. Not everyone can afford to buy that hallowed toothpaste that’ll supposedly change your life for the better. What he’s created is an atmposphere of inadequacy. Like the way we treat our purchases, people treat Leonard. He’s not the best option. There’re better, richer, more handsom men. There are Dons. But not everyone can be a Don. There isn’t enough money to go around.

Don ran into a multitude of American failures while driving across the country. All young, all disillusioned by the unrealized potential of the ‘60s, by Vietnam, by Altamont, by JFK’s death. And you can see glimmers of them—like the receptionist with the rid-ribboned braids—in his Coca-Cola ad that plays the series out. This is Don making amends. This is Don as an optimist. He’s once again reinvented himself. This time for the better.