By Mikhail Karadimov February 27th, 2017

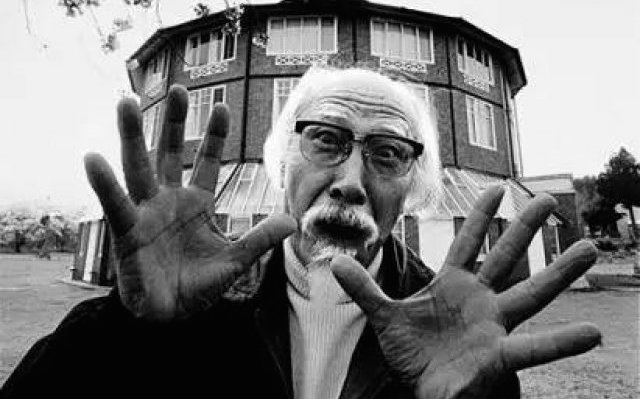

Word’s finally reached me: Suzuki Seijun’s passed away a couple of weeks ago. Right before Valentine’s Day. (At least he didn’t have to live long enough to see his wife and/or girlfriend disappointed with his last minute Valentine’s plans.)

Seeing the obituary before me on my phone—with the eleven day delay—I thought I should celebrate the man’s renegade career with a few words.

Like many other Japanese directors coming out of the New Wave movement in the late-50s/early-60s Suzuki wanted to break away from the likes of Kurosawa, Ozu, and Mizoguchi; he wanted to break away from their traditionalism, their constant preoccupation with old vs. new. All he wanted was the new. A self-prescribed high order.

Suzuki was mainly a Nikkatsu man when the studio’s main interest was combatting the dawn of television with yakuza pictures—Suzuki’s bread and butter. Due to the mind-numbing reputation of the genre’s formula—cookie-cut characters framed against the same several plots—Suzuki eventually grew bored with these assignments and decided Hence the existence of films like Tokyo Drifter (66), Fighting Elegy (66) and Branded to Kill (67).

He continued with the yakuza pictures—the “coolness”, the violence, the recycled storylines—but he did so by following his own idiosyncratic recipe. He started jump cutting, freezing frames, fucking with exposure by washing entire moments out, experimenting with lighting and blocking—in short: he went New Wave on us.

The thing about Suzuki is that he had ambitions higher than that of the studio system’s ceiling. He liked subverting the yakuza pictures as one big middle finger to Nikkatsu, but he still wanted to aim higher; he wanted to point a finger at both sides of Japan’s ideological coin—left and right—and admonish Japan for its oppressive, binary ways. Something I think he achieves with great swagger in the hilariously kinetic Fighting Elegy.

https://youtu.be/j4Hy7WJtnI8

Unlike his other films, there aren’t any yakuza to be found in Fighting Elegy. Don’t get me wrong: there’s still plenty of fighting, fucking, and other instances of high-flung debauchery. Actually, in my opinion, the film has one of the most brutal, most exhausting fight scenes I’ve ever witnessed, rivaling even the no-holds-barred ridiculousness of John Carpenter’s They Live, in which Rowdy Roddy Piper and Keith David beat the snot out of each other in an abandoned alleyway.

The film shows just how militaristic and fascistic the left can be, too—which isn’t all that far off from America’s current political climate. Kiroku’s a sweet boy, an awkward boy, who’s all about Jesus Christ. He’s in love with the young woman sharing his home. He thinks her a perfect angel with the most porcelain perfect hands. She’s so perfect, in fact, that he—with strenuous difficulty—resists the urge to masturbate upon her image. Instead—to let the lead out—he joins a local gang and turns to schoolyard violence. It’s the men in his life—his mentor, his peers—who tell him that he needs to get hard, to whip people up, to bash his way through life, if he wants to look the part of the man.

Of course, all this posturing and fisticuffs leads him astray. He hardens up, loses touch with his more creative, thoughtful side, and eventually hightails it to Tokyo for the 2-26 Incident: a day in which a group of young officers from the Imperial Japanese Army attempted to overthrow their ideological enemies—a truly fascistic display of misguided angst—angst created by centuries and centuries of oppression, of fighting what the body wants and needs to keep it sustained and whole.

Fighting Elegy is a perfect encapsulation of Suzuki’s life and career as well as his battle with Nikkatsu and all other studios who refused him his purely singular voice.

I’d say “rest in peace”, but I know you’ve still got plenty of fight left in you, Suzuki-san. May you continue to lash out at any and all atrocities, even in the afterlife.