As I wrote in an earlier post about director Werner Herzog and Klaus Kinski, I’m fascinated with creative partnerships between directors and actors that persist over several films. The history of film has so many memorable duos along these lines but only a handful that are as interesting and artistically rewarding as that between Josef von Sternberg and Marlene Dietrich. Together they made seven movies between 1930-1935, many of them I regard as essential classics, and while they both made worthy movies separately, when working together they tapped into that rare vein of cinematic gold and told stories in a unique style unlike any other movies I’ve ever seen. No matter what the vehicle for Dietrich was or what exotic locale von Sternberg was expertly creating on a sound stage, the two of them created a fantasy, an exotic woman capable of love but who would often lure men to their doom on the screen and off. In his memoir, von Sternberg writes, “Some of the admirers she subsequently collected came to me to state bitterly that they had sought in vain the image of her that flashed on the screen. Amusingly enough, a famous writer who should have known better went so far as to say that I had done him considerable harm by endowing her with a personality not her own. I did not endow her with a personality that was not her own; one sees what one wants to see, and I gave her nothing that she did not already have.” The movies speak for themselves: The Blue Angel/Der Blaue Engel (1930), Morocco (1930), Dishonored (1931), Shanghai Express (1932), Blonde Venus (1932), The Scarlet Empress (1934), and The Devil is a Woman (1935). Their working relationship was absolutely fascinating, one of absolute trust when it came to the filmmaking process and this trust played an essential role in Dietrich’s assent to superstardom all while von Sternberg became positively reviled in Hollywood for his reputation as a brilliant but arrogant control freak. I think von Sternberg is one of the greatest filmmakers that ever lived but he seems to have enjoyed courting the hatred of others with his disdain for those he considered impediments or distractions to his vision. In his retirement, Josef von Sternberg wrote an incredibly entertaining autobiography, Fun in a Chinese Laundry, and his chapter on his relationship with Marlene Dietrich is absolutely delicious reading. The book can be hard to find but I can’t resist the opportunity to share a few passages (Disclaimer: I do not own the rights to “Fun in a Chinese Laundry”. It is not my intent to plagiarize this amazing book but rather to celebrate some extraordinary samples.)

Josef von Sternberg was already a famous filmmaker when he accepted a job in Germany directing the film that became The Blue Angel (1930), a project that would be shot simultaneously in German and in English (stick with the German version). Von Sternberg was already a master visual stylist who preferred working on sound stages where he had total control over the lighting and the production design. Several of his silent films are some of the best of that period (Underworld (1927), The Last Command (1928), The Docks of New York (1928)) and with The Blue Angel he successfully made the transition to the sound era, a transition that ruined many filmmakers and actors that were less adaptable. Marlene Dietrich had been labeled box office poison in Germany from several flops in which she had appeared, but von Sternberg was convinced that she was perfect for his film and fought his German producers and cast in order to cast her in the part of Lola. When making a test scene with her, he writes “I then put her into the crucible of my conception, blended her image to correspond with mine, and, pouring lights on her until the alchemy was complete, proceeded with the test. She came to life and responded to my instructions with an ease that I had never before encountered.” When shooting began on the film, he found in her the perfect collaborator. In spite of the later complications in their relationship, he never ceased praising her for ability to take direction. “Her behavior on my stage was a marvel to behold. Her attention was riveted on me. No property master could have been more alert. She behaved as if she were there as my servant, first to notice that I was looking about for a pencil, first to rush for a chair when I wanted to sit down. Not the slightest resistance was offered to my domination of her performance. Rarely did I have to take a scene with her more than once.”

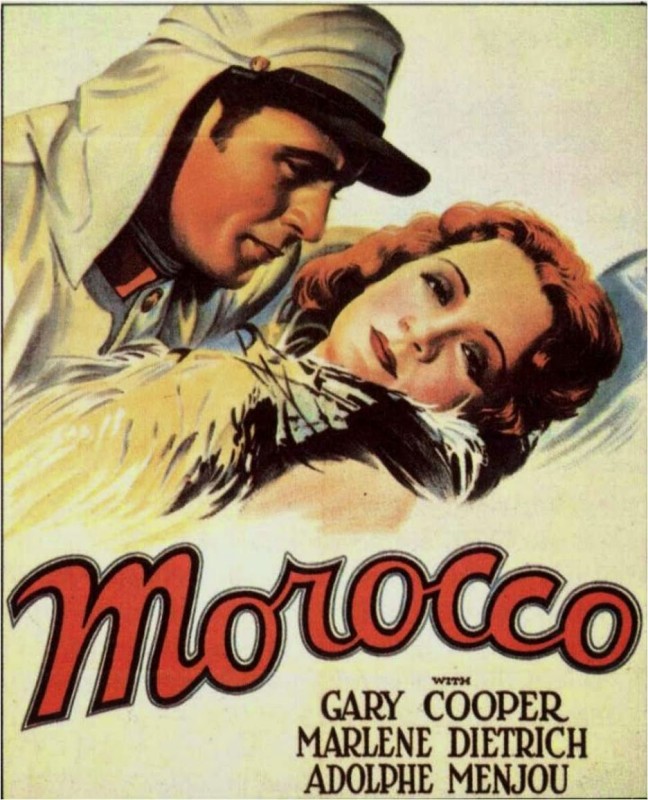

While still shooting The Blue Angel, von Sternberg sent his test footage of Dietrich back to Paramount and they promptly offered her a contract and the lead on von Sternberg’s next film in Hollywood. Von Sternberg shared the news with Dietrich and infuriated her by telling her she had five minutes to make up her mind. Von Sternberg admits in his book that he made a huge error putting this kind of pressure on her but soon enough they were in Hollywood shooting Morocco with Marlene starring opposite Gary Cooper, a film that saved Paramount and would turn Dietrich into Hollywood royalty. Dietrich’s trouble with English delayed the shoot initially and von Sternberg was nearly replaced as the director for the delays in spite of never going over budget and eventually catching up with the schedule. When commenting on the rotating roster of studio executives he worked with, von Sternberg wryly observes, “The history of a film studio is like the history of the guillotine: each head is followed in turn by the head that had arranged the previous decapitation.”

At any rate, Morocco became a smash hit and audiences became enamored with Marlene. In interviews, she spoke of von Sternberg’s total control over her performance and her fans ate it up. They came to view her as the victim of a tyrannical artist gone mad, and her star continued to rise while von Sternberg became an object of ridicule in Hollywood for the degree of control he demanded while on a film set. Many fans felt that von Sternberg was somehow ruining Dietrich’s career with his incredible demands. What audiences failed to understand was the degree to which the star they loved simply didn’t exist. Her characters were fantasies of smoke and mirrors created by two collaborators working at the peak of their abilities. Looking back on her stardom, von Sternberg states, “Men wished to lay fortunes at her feet, and celebrities vied with each other to be seen and photographed with her. Tribute was collected from men of rank and fame, the most famous actors wished to have her as their partner, producers and directors couldn’t wait until they could work with her, and her circle increased to include the top writers and creators of her day. Dukes and generals and even the heads of nations wanted her to grace their tables. One journalist, quoted in one of the many books devoted to her, not only raved about her beauty but ‘rated her brains on a par with those of Napoleon, Caesar, Mussolini and Lenin’. Opposed to this pinnacle of glory was her position on my stage. Here was no enthusiast, but a cold-eyed mechanic critical of every movement. If there was any flattery, it was concentrated in a ‘That’s fine, it will do.’ More often she listened to ‘Turn your shoulders away from me and straighten out … Drop your voice an octave and don’t lisp … Count to six and look at that lamp as if you could no longer live without it…Stand where you are and don’t move; the lights are being adjusted’.” One gets the sense that von Sternberg loved the exposure and the success their relationship brought them, but his intimate relationship with Dietrich was becoming increasingly complex.

I have never read any confirmation that Marlene and Josef were lovers, but interviews with friends, coworkers and family members suggest an intense private relationship between the two of them that was physical even when Dietrich was involved with other men. Dietrich’s daughter maintains that Josef von Sternberg was deeply in love with Marlene for his entire life. I can think of no more intimate connection between director and star and this connection can be felt in every frame of film he ever shot of her. No actress has ever been photographed more beautifully than Dietrich by von Sternberg, a fact that would come to hurt her in later films when she worked with filmmakers unable to match von Sternberg’s superb lighting and shot composition. Their film Shanghai Express was their greatest commercial success and one of my favorite films of the 1930s. The subtle, suggested eroticism of their films was the perfect approach to the Pre-code tastes of the early 1930s but unfortunately the tastes and standards of the times would rapidly become more conservative. Blonde Venus and The Scarlet Empress are excellent movies. Most film historians regard The Scarlet Empress as their finest achievement. But the films stopped performing well at the box office and the turbulent love/hate relationship between von Sternberg and Dietrich was rapidly running its course.

To the bitter end, they continued to trust one another artistically. Von Sternberg writes about a particular scene from their last film, The Devil is a Woman, where he used a small rifle to pop a balloon in front of Dietrich’s face to introduce her character. “When the scene began, I took aim and exploded the concealing balloons to reveal one of the most fearless and charming countenances in the history of films. Not a quiver of an eyelash, nor the slightest twitch in the wide gleaming smile was recorded by the camera at a time when anyone other than this extraordinary woman would have trembled in fear.” One could argue that stunts such as these only reinforced Josef von Sternberg’s increasingly negative reputation but it is difficult to argue with the results on the screen. They made pure movie magic. When the two parted ways, von Sternberg took a very long vacation while Dietrich went to work on a series of lesser movies. Looking back decades later, von Sternberg reflects, “I was told that during the many films made after my ‘fiasco’ with her she would often go through a scene and finish it by whispering through the microphone, ‘Where are you, Jo?'”

In my opinion Dietrich and von Sternberg were never better than when they worked together. Many of Josef von Sternberg’s peers from that time believe that von Sternberg’s turbulent relationship with Dietrich eventually broke him causing his work to suffer for many years to come. He lost control over several of these productions and for years went into a self-imposed exile. Later he came out of retirement to make the brilliant Anatahan (1953), but he never regained the success he enjoyed while working with Marlene. Marlene Dietrich, on the other hand, remained a star for years working with many fine filmmakers including but not limited to Billy Wilder, Ernst Lubitsch, Raoul Walsh, Alfred Hitchcock, Orson Welles and Fritz Lang. I absolutely adore her chemistry with Orson Welles in “Touch of Evil” and have a special place in my heart for “Rancho Notorious” but to be fair, Marlene was never the same once she parted ways with von Sternberg. But even if neither of them had ever worked again, we are left with the films, and what incredible films they are. The films are the product of a unique relationship and a unique time and place in history and we should feel fortunate as movie fans to be able to look back in awe at this bizarre doomed romance of the movie business.

I am one of the Co-Hosts of the podcast Wrong Reel and you can find our material here:

Check us out on Stitcher radio

For anyone interested in Josef von Sternberg’s silent films, Criterion released an excellent collection. Here is the trailer.