By James Hancock November 15th, 2015

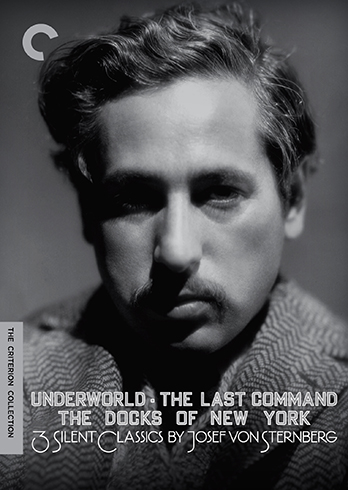

Before I say anything about Josef von Sternberg, I have to acknowledge that this post is doomed to fail from the outset. Guy Maddin already tackled this subject in one of my favorite film essays ever written ‘Mit Out Sound, Mit Out Solution’ for Criterion back in 2010 and for my money Maddin’s skills as a film historian are just as compelling as his extraordinary talent as a director. The best I can hope for with this post is simply to try and steal as little as possible from Maddin’s observations and find a way to contribute something new to the conversation. When Aaron West announced the Criterion Blogathon, I knew immediately that I wanted to use the opportunity to celebrate the work of Josef von Sternberg, an astonishing director who fetishized each and every frame of film he ever shot. My obsession with film history can be traced back to a single screening in college when I first saw von Sternberg’s The Blue Angel (1930). The film hit me like a bolt of lightning and ignited an appetite for old movies that has never abated. I quickly saw the rest of the films in the legendary seven-film collaboration between Josef von Sternberg and Marlene Dietrich but foolishly neglected the rest of von Sternberg’s filmography for many years assuming erroneously that there was nothing I needed see before or after his work with Dietrich. Rarely have I been so happy to be so wrong. I soon learned that there were many chapters to his career before and after his relationship with Marlene. Von Sternberg was a master storyteller who used the resources of the soundstage with the strictest of discipline in order to let his imagination run wild with tragic tales of violence, love and taboo. Thanks to the good people at Criterion Collection, we can now fully appreciate the best of von Sternberg’s silent films, Underworld (1927), The Last Command (1928), and The Docks of New York (1928), which were lovingly restored for a DVD boxed set released by Criterion in 2010. The films were a total revelation when I first saw them, one that made me realize that even if Josef von Sternberg had never made another movie past the 1920s he would be still be regarded as one of the greatest directors who ever lived.

In preparing for this post, I relished the excuse to crack open my rapidly disintegrating copy of Josef von Sternberg’s memoir, Fun in a Chinese Laundry (1965). It is hard to describe how von Sternberg is able to come across as both a rational humble man and an egotistical tyrant all at once, but that is part of the von Sternberg mystique. Throughout his career von Sternberg seemed to enjoy courting the hatred of his coworkers, critics and the public all while stirring their passions to delirious heights with films unlike any ever made. There are too many brilliant anecdotes and reflections in the book to recount here but suffice to say the book might have the most entertaining chapter of film history ever written where von Sternberg describes his years of working with Marlene Dietrich. But more important to the point of this post, the book offers many details on the years where von Sternberg learned his craft making silent films. He first attracted the attention of Hollywood in 1925 with a low-budget independent film The Salvation Hunters. Charlie Chaplin was impressed and recruited von Sternberg to direct A Woman of the Sea otherwise known as The Sea Gull starring Edna Purviance. For reasons that are not entirely clear, Chaplin showed the film only once before locking it away in a vault before it was presumably destroyed. With his career already in jeopardy before it even really got started, Von Sternberg retreated into the role of working as an assistant director. But he saw his chance at a comeback when hired by Jesse L. Lasky of Paramount to direct Underworld, a gangster film that would dramatically alter the trajectory of von Sternberg’s career.

With Underworld, von Sternberg established a pattern that would repeat itself throughout his career. In spite of heavy obstacles both during the production and release of the film where von Sternberg appeared surrounded by enemies (real and imagined), von Sternberg managed to craft a beautiful tale filled with decadence and violence. Totally bewildered by the final product, Paramount threatened to shelve the film indefinitely. Cooler heads prevailed and Paramount decided to show the movie in New York with no publicity of any kind at 10 AM hoping that no critic would be awake to see it. By the end of the day, Times Square was mobbed with people trying to see the film, one that whetted the public’s appetite for gangster movies for many years to come. Underworld not only became a massive hit with the public but also won an Academy award for writer Ben Hecht who had tried unsuccessfully to have his name removed from the film prior to its release. The film presents a classic love triangle between the criminal equivalent of Attila the Hun, his lady, and a recovering alcoholic who owes his new purpose in life to his physically imposing friend. George Bancroft plays the role of the gangster Bull Weed who spends most of the movie kicking people out of his way all while his best friend played by Clive Brook quietly falls in love with Bancroft’s girlfriend. Bancroft was never better than in this larger-than-life performance, one filled with incredible contradictions such as when he sits down with a kitten and seems almost embarrassed as he feeds it milk from his fingertips. The tension of this love triangle leads to an epic conclusion with the characters under siege by police firing on them from all sides, one that would be imitated in countless future gangster movies. If you consider yourself a fan of Little Caesar (1931), The Public Enemy (1931) and Scarface (1932), your education is incomplete until you have seen this classic gangster film.

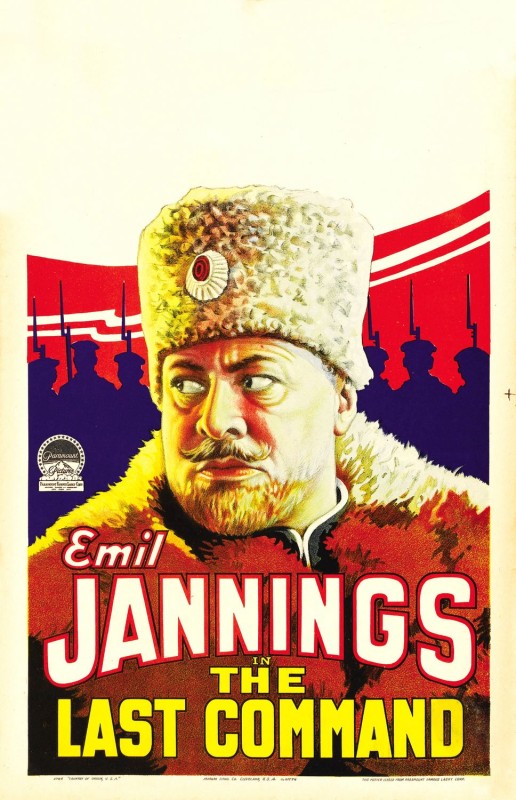

My favorite of the films in this collection is The Last Command, a movie that gave von Sternberg the chance to make his most searing indictment of the brutal indignities of the movie business. The story opens on a pitiful old man played by Emil Jannings, one who is afflicted with the shakes due to an extreme shock. He survives as an extra working for $7.50 per day in an industry that laughs at his claims of having once served the Russian czar as Grand Duke Sergius Alexander, an Imperial General who was forced to flee the country during the Russian Revolution. But a director named Lev Andreyev, played to perfection by the young William Powell, recognizes him from his years fighting against the czar and decides to torture Jannings emotionally by hiring him essentially to play himself in a movie about the Russian Revolution. What is so brilliant about this movie is the framing device, a storytelling approach that opens with a behind-the-scenes look at the making an epic through the eyes of an poverty-stricken extra before transitioning to a flashback where we see Jannings at his most magisterial during his time as a general. While the czar and his cronies are depicted as corrupt despots, Jannings is incredibly sympathetic due to his overwhelming love for Russia and its people in spite of his loyalty to a man for whom he has no respect. In Fun in a Chinese Laundry, von Sternberg laughs at the irony of how his total ignorance of Russia proved to be no obstacle in making a great movie. His unleashed the full powers of his imagination creating an emotional truth that many Russians found incredibly compelling. Conversely, he was all too familiar with the dark side of Hollywood and portrayed the industry in such a way that once again his film was threatened with not being released. The film was saved by the most unlikely person imaginable, Otto Kahn, one of the financiers who called the studio a pack of idiots and demanded the film be released as planned. One of the most emotionally moving of von Sternberg’s films, many of the themes explored feel like a warm-up for Jannings and von Sternberg’s later collaboration The Blue Angel. Both men possessed legendary egos and the two swore never to work together again after clashing on The Last Command, but thankfully for us, they buried the hatchet and were reunited barely two years later for one of the best movies ever made.

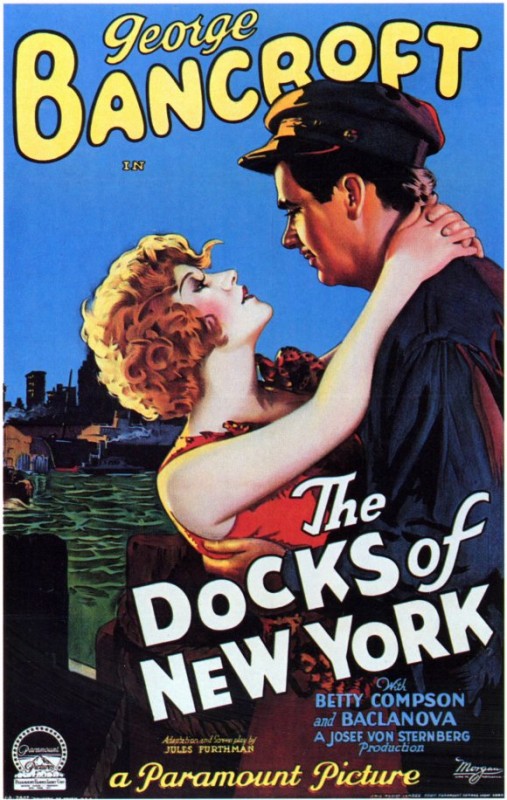

The Docks of New York is one of those rare silent films where the cinematic grammar of telling a story in pictures has become so sophisticated it is enough to make one yearn for an alternate reality where the silent era lasted another decade. The cinematography (by Harold Rosson) and the gliding camera movements throughout the film are some of the most exquisite of von Sternberg’s career. While no less decadent than von Sternberg’s previous efforts, the film is far more intimate in scope with an epic of the human soul about a ship stoker played by George Bancroft falling in love with a suicidal prostitute played by Betty Compson. This story marks the first collaboration between von Sternberg and the brilliant screenwriter Jules Furthman who would later write Thunderbolt, Morocco, Shanghai Express and Blonde Venus for von Sternberg. Most of the film takes place in a wharf pub where the behavior of the patrons is unhinged to put it mildly. The atmosphere of the bar, however, is the real star of this show, an atmosphere that anticipates the scandalous cabaret featured in The Blue Angel. As much as I enjoy some of George Bancroft’s later work in talkies like Stagecoach (1939), he was at his best in the silent era where he used his bulk and overwhelming masculinity to incredibly expressive effect, in particular in scenes where he was required to show tenderness and love. Surprisingly, von Sternberg barely mentions this film in Fun in a Chinese Laundry. From my point of view, The Docks of New York is a powerhouse love story that deserves to be mentioned in the same breath as D.W. Griffith’s Broken Blossoms (1919) and F.W. Murnau’s Sunrise (1927).

The transition from the silent era to sound left many careers in ruins but Josef von Sternberg is one of a handful of great directors like Ernst Lubitsch and Fritz Lang who appear to have effortlessly made the switch. Sadly his transition film, the part-talkie Thunderbolt (1929) has been lost to the ravages of time like far too many other films from that period. Thunderbolt was one of many ‘goat gland’ movies where talking sequences were inserted into a silent film to make it commercially viable. For a definition of ‘goat gland’, see my earlier post on Guy Maddin. For reasons that I can’t properly articulate I am completely obsessed with the late Twenties/early Thirties and no director defines this period for me better than Josef von Sternberg. For now, these extraordinary silent films are not available online (at least legally) and the DVDs can be hard to find. My hope is that Criterion makes these pristine prints available on Hulu or some other Criterion-friendly site in the near future. They deserve to be as widely seen as The Blue Angel, Morocco, Shanghai Express, Blonde Venus and The Scarlet Empress, the films upon which von Sternberg’s reputation rests. An impressive list of films to be sure, but von Sternberg accomplished so much more. For me, discovering his silent films was akin to discovering the silent films of F.W. Murnau and Fritz Lang for the first time. Sadly von Sternberg’s professional career began to crumble in the late Thirties. The hostile perfectionist who had cultivated an air of elitism for so many years gave his critics and enemies a chance to sharpen their knives when his films started to underperform commercially. Gradually he retreated from the movie industry, but he came back with one final masterpiece in 1953, Anatahan. With his mastery of lighting, von Sternberg made a low-budget Japanese film shot on cardboard sets look and feel like an epic from the Golden Age of Hollywood. As late as 1969, von Sternberg taught a masterclass in lighting (see video below) revealing that he still had full control over his talent to his dying day. Von Sternberg claims he never actively courted people’s dislike but that he simply found it too exhausting to use energy pretending to like people. All that really matters now in 2015 is his cinematic legacy. No matter what people thought of him at the time when working with him or whatever von Sternberg might have thought of himself, his films represent a unique body of work, one that will have my undying admiration for as long this addictive mistress of film has its hooks in my mind and imagination.

I am one of the Co-Hosts of Wrong Reel and you can find more of our content here:

Join the Conversation on Twitter

https://youtu.be/kyWiz9JMalg

Documentary about von Sternberg’s 1937 attempt at filming ‘I, Claudius’.