By James Hancock July 27th, 2015

‘I only make shit,’ Mario Bava famously once stated about his own work and for cinephiles who can only think of Fellini, Rossellini, De Sica, Antonioni, or Visconti when discussing Italian film they might be inclined to agree. Mario Bava worked with very small budgets and throughout the 1960s and 1970s churned out a wide variety of genre films that eventually ended up in drive-in movie theaters and grindhouses across the United States. But for a director who supposedly only made shit, his work continues to inspire filmmakers to this day. Filmmakers as varied as Martin Scorsese, John Landis, Joe Dante, Quentin Tarantino and Edgar Wright are all vocal admirers. I’ve feigned an appreciation for Bava for years mostly because of the gorgeous posters for his movies as well as a really great moviegoing experience I once had at the LACMA where Barbara Steele introduced Mario Bava’s Black Sunday (1960). Recently I decided it was time to fill in this gap in my education assuming at first that I’d see a few of his better known films and call it a night. Now, twelve movies in with a few more that I still plan on seeing, I’m ready to declare myself officially a hardcore fan of Mario Bava, a director to whom anyone making slasher films, sci-fi, gothic horror, mysteries, thrillers or superhero movies owes a debt of gratitude. While the screenplays he worked with were often uneven in quality, I don’t think any filmmaker working in the horror genre has ever shot better looking movies. Mario Bava blazed the bloody, almost hallucinatory trail that allowed Italian horror masters Dario Argento and Lucio Fulci to follow in his illustrious footsteps. If plot-driven, gorgeously shot, low-budget genre films are not your thing, Mario Bava may be too much for you. But for anyone with a love of Hammer Horror films, the spaghetti westerns of Sergio Leone & Sergio Corbucci, Master of Horror John Carpenter, or the exploitations films of Jack Hill, sooner or later they need to set aside some time and reckon with Mario Bava’s incredibly diverse body of work.

Mario Bava’s father Eugenio Bava was a cinematographer in the early days of the Italian film industry and after some time studying as a painter Mario Bava eventually followed in his father’s footsteps and worked as a cinematographer for many years. His time spent as a painter and lighting films would pay off off huge dividends later in his career. Bava finally got his chance to make his switch to the director’s chair on what some consider to be the first Italian horror film, Lust of the Vampire (1957) when the director Riccardo Freda suddenly quit the film halfway through production. For the next few years Mario Bava played a hand in finishing and/or co-directing other productions during which time he mastered the low budget special effects of using miniatures, models and matte paintings essential to making his low-budget movies feel much more epic in scope than his small budgets would otherwise allow. In 1960 he finally made his incredible debut as a director with Black Sunday, a movie that many of his admirers still consider his best. The trailer that I’ve linked below is but a small taste of this amazing horror film. As I mentioned earlier, Bava’s films are all over the map in quality but from Black Sunday onward Bava always shot the hell out of his movies with some of the most gorgeous photography and lighting ever seen in the sub-genres in which he thrived.

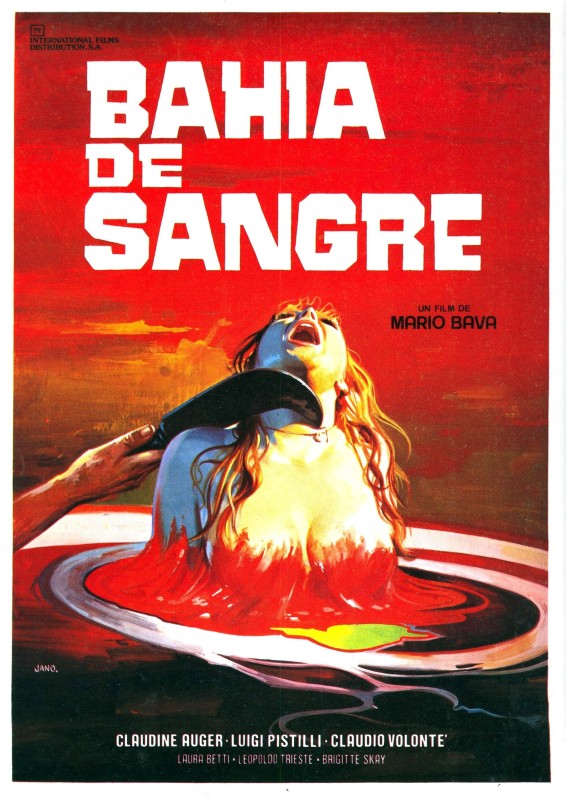

One of the biggest revelations from watching Bava’s movies is how I’ve been forced to question a lot of my assumptions about film history and the origins of the slasher genre. As a kid I fell in love with slasher movies and as I learned more about film history, I accepted the US-biased narrative that the genre was developed by guys like Wes Craven (The Last House on the Left), Tobe Hooper (The Texas Chainsaw Massacre), John Carpenter (Halloween) and Sean Cunningham (Friday the 13th). What I did not know until a few days ago is that Mario Bava laid down the foundation for all the slasher movies to come. A Bay of Blood (1971) perfectly establishes the template where a group of horny teens/twenty somethings gather at a lake only to be systematically picked off in increasingly elaborate death scenes. One killing in particular is so disturbing that I’ll never look at an octopus in quite the same way again. What really caught me off guard was how much material has been stolen outright from A Bay of Blood by other slasher films. One of the most famous death scenes from the Friday the 13th franchise is in Part 2 where Jason skewers a couple during the wondrous exchange of bodily fluids by plunging his spear through the couple, the bed, and into the floor below. Bava beat Jason by a good ten years with the exact same sequence in A Bay of Blood (see picture below).

I’ve also always assumed erroneously that the slasher film evolved out of the traditional horror genre. I know now that a case can easily be made that it evolved straight out of Italian Giallo, a genre of popular paperback novels in Italy typically featuring lurid covers with images of rape and murder. Italians use the term Giallo for any thriller, but for the rest of the world, Giallo describes a particular kind of murder mystery usually one that is heavily erotic in tone. Bava took this trend and made it his own with Blood and Black Lace aka Sei donne per l’assassino (1964), a film that Quentin Tarantino particularly loves and once tried to rerelease in the United States. While many in the US do not give Bava the credit he deserves for inventing the slasher genre, nobody tries to deny the role he played in adapting Giallo to film, igniting a craze for these types of erotic thrillers that many Italian filmmakers imitated for many years after the film’s release. Bava would return to this style of storytelling repeatedly throughout his career. What I love in particular about Blood and Black Lace is the look of the villain. I’m obsessed with comic books and masked vigilantes but what most superhero films today ignore is the appeal of a great villain. Blood and Black Lace features a diabolical villain whose style looks identical to the Question (or Rorschach depending upon what generation you’re from). While I might have to stretch the definition of a superhero movie to the breaking point to include this movie, for me this is an essential film about a supervillain on a murderous rampage through the world of high fashion and supermodels.

No, that isn’t the Question nor is it Rorschach, but rather the main villain in Mario Bava’s ‘Blood and Black Lace’ (1964).

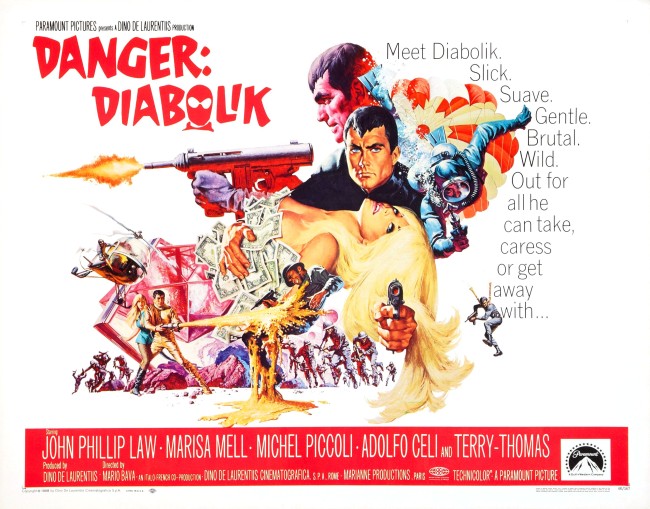

One of Bava’s greatest strengths as a director was using every filmmaking trick he could think of to make his movies look and feel like a giant Hollywood production. In the video below Edgar Wright recounts a famous story where producer Dino De Laurentiis offered Mario Bava a $3 million budget to make Danger: Diabolik (1968) to which Mario Bava replied, ‘I can do it for $500,000.’ The resulting film might be the best of Bava’s career. Danger: Diabolik defies easy categorization. Imagine a James Bond film from the 1960s where Bond goes completely insane and decides to strut around in black leather outfits, killing people at will and stealing everything in sight in order to entertain his supermodel girlfriend. Now add some mind-altering substances for the viewer and you’re starting to get close to the delirious frenzy of this flick. What really pushes this movie over the cliff into sheer moviegoing nirvana is the score by Ennio Morricone, one of the most unusual of his career. Only the late 1960s could produce a film as esoteric and surreal as this and if for whatever reason a person is unwilling or unable to enjoy this film, that person should just give up on movies altogether.

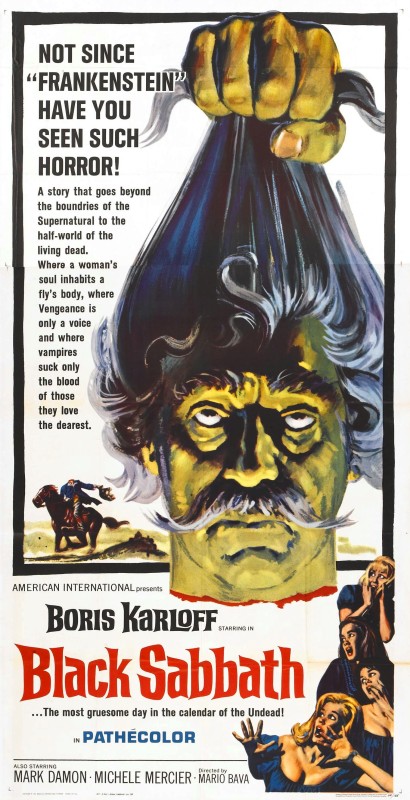

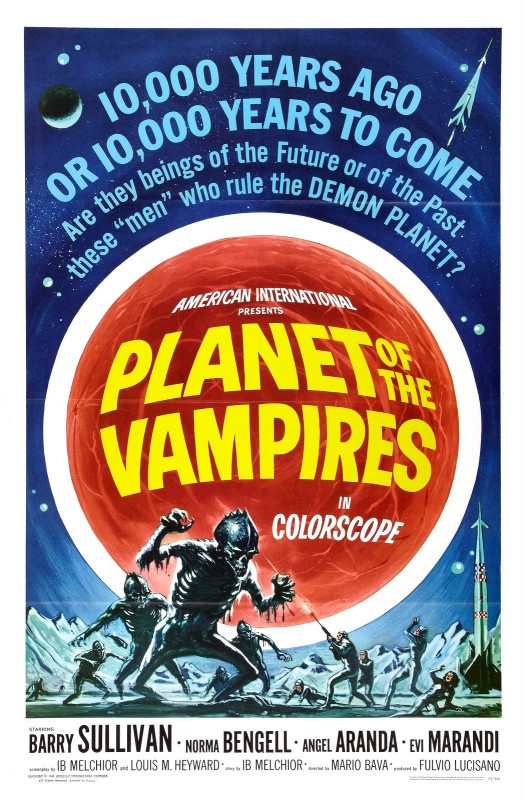

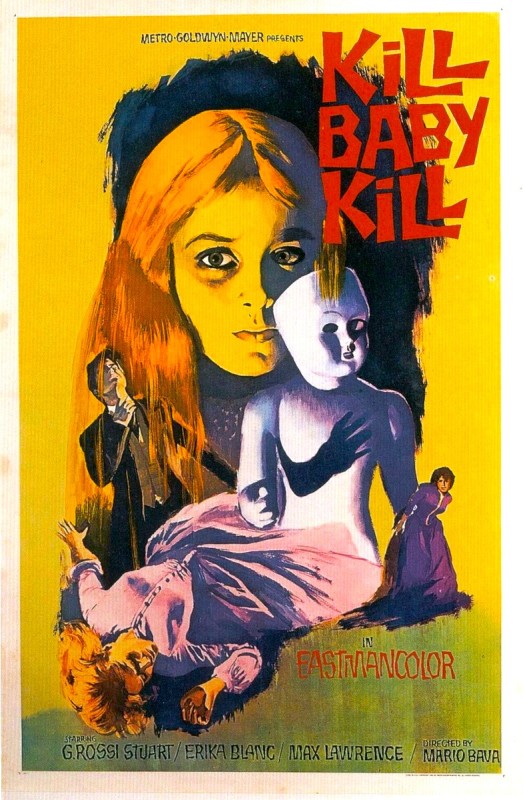

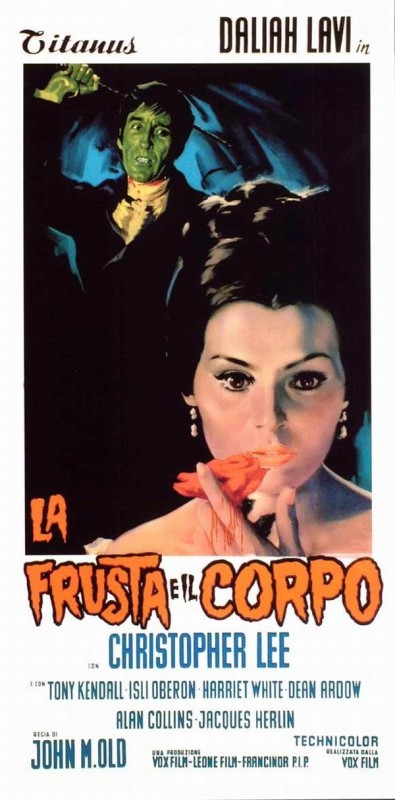

The good news is that Bava’s films are readily available for rediscovery for anyone interested in hunting them down. Between Fandor, Amazon Instant Video, Netflix, and YouTube I was able to find pretty much every film of his that his fans argue are required viewing. Some of his films like Lisa and the Devil (1973) have different versions floating around or different language tracks but for the most part, Bava’s filmmaking legacy is intact and I think his influence will only grow over time while some of the more respectable members of the Italian filmmaking community from that period will increasingly see their work exhibited exclusively in museums or high brow revival houses. Somewhere right now, there is a kid discovering Bava the same way Tarantino discovered the delicious anthology horror film Black Sabbath (1963) on late night television. Or there is a young aspiring filmmaker like the 24-year-old Martin Scorsese who was blown away by Bava’s classic ghost story Kill Baby, Kill (1966). Bava’s influence and DNA can be seen in so many movies such as Ridley Scott’s Alien which is almost impossible to imagine without the risks that were taken by Mario Bava with Planet of the Vampires (1965), a movie that plays like the most hardcore, nightmarish episode of Star Trek ever made. Bava died prematurely at age 65 in 1980, sadly frustrated with a career that was stagnating with movies that were either never released or re-cut in ways that distorted his original intentions. Luckily his work is being preserved and restored as was the case with Rabid Dogs (1974) a movie that was never shown publicly until it was finished and released on DVD in the 1990s. Rabid Dogs is an absolutely savage movie reminiscent of the darker films of Sam Peckinpah. Not every movie by Bava is a home run, far from it. There are a lot of 2nd tier and 3rd tier Mario Bava movies like Baron Blood (1972) and 5 Dolls for an August Moon (1970) that even his most devoted admirers would have trouble defending with a straight face. But in digging through these movies like a crazed celluloid archaeologist, you occasionally stumble upon obscure gems like The Whip and the Body (1963, directed by Bava under the pseudonym John M. Old), a ghost story staring horror icon Christopher Lee featuring such shocking sadomasochism it is a marvel that the movie ever got made at all.

So at the risk of belaboring the obvious, I am a fan, but Mario Bava’s movies will not appeal to everyone. Plenty of devoted film lovers will find his movies to be in exceptionally poor taste or downright offensive but I’d argue that these same moviegoers have lost sight of the raw, visceral pleasure a good midnight movie has to offer. The world of grindhouse cinema throws the Hollywood rulebook out of the window and presents a world of unfiltered, vital emotion and shock value that often lingers on the brain far longer than many essential classics. Just about anything can and does happen in the world of low-budget genre films. There is a special breed of cinephile out there, and they know who they are, that loves nothing more than seeing directors excessively abuse the zoom lens or assault the senses with nightmarish color palettes. This is the domain of Mario Bava and in his way he was the lord and master of one of the darkest chapters to be experienced in all of film history.

I am one of the Co-Hosts of Wrong Reel and you can find our content here:

Join the Conversation on Twitter