Cheatin’

dir. by Bill Plympton

Bill Plympton fancies himself a renegade of American animation. His style’s as raw as it gets. Not at all interested in the polished sleekness of today’s computer-animated fare, Plympton doesn’t bother hiding his labor. His sketch lines run wild upon the screen. You can see all the squiggles and scribbles roiling within the characters’ forms, how the countless pencil etches bounce around like little Mexican jumping beans. It’s equal parts kinetic and careless. On the one hand, defenders of Plympton’s still unreleased Cheatin’ can say that all those little imperfections, those blissful accidents of carbon fiber, are organic representations of the inner turmoil charging the film’s lead couple to act. Or, you can simply write it off as plain ol’ laziness.

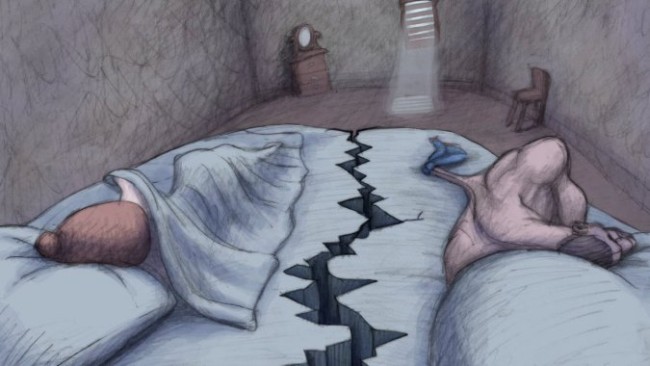

Cheatin’ concerns itself with a highly volatile, highly electric couple: Ella and Jake. It’s one of those “he treats me terribly because it’s the only way he knows how to love” kind of dynamics. According to a shot that “dollies” bird’s-eye-view over Ella and Jake’s long-neglected house, all the two have on their brain is unobstructed babymaking, nothing more, nothing less. Other than sex and the fact that Jake’s knight-in-shining-armor yins with Ella’s damsel-in-distress yang, we have no clue what keeps these two together. One day, while indulging Ella in a shopping spree, one of Jake’s many lady admirers ensnares him in a simple and creatively uninspired misunderstanding, which then causes him to seek sexual catharsis outside the homestead.

It’s a very thin and loose plot, so much so that I’m hesitant to call it plot. The film unravels without much direction or motivation. There are stretches of the it that feel as if Plympton no longer knew where he was going—or even worse: that he no longer cared. The film proves most muddled in its set-up and denouement. The construction is hazy and lackadaisical at best, and often times straight-up confusing. I’m still not quite sure what it is that compels Ella to participate in the round of bumper cars that serendipitously thrusts her into Jake’s life, nor what feat of magical trickery pushes them back together. The laws that govern this particular sphere of “reality” are altered and re-altered so often that you start to wonder if Plympton even knows what’s up. Judging by his post-screening Q & A at the New York Institution of Technology? Not really.

Like Sylvain Chomet did with the masterful Triplets of Belleville and The Illusionist, Plympton stretches and caricaturizes his characters with elongated absurdity. UNlike Chomet, he picks out his characters’ one defining quality and amplifies it to a point of shallowness. Jake is nothing more than a top heavy hammer, stacked out wide with a pair of cinderblock pecs, while Ella swings and sways lasciviously with hips that hypnotize like a pendulum. That’s all they are: electrically-charged stand-ins for violence and sex. Consequently, it’s only during the scenes regarding Plympton’s obvious obsession with violence and sex—and how the two sometimes fuse together to create a transcendent kind of harmony—that the film intermittently connects.

Coming out of the screening, I kept hearing people chatter and effervesce over the old-school efforts put into producing the film’s idiosyncratic visuals, as if effort alone made the film an experience worth having. Plympton drew every single frame of the film himself. Surely, a fact worth considerable praise within itself. But does it really matter how much he labored if the end product is devoid of any and all purpose? No. It does not. Films need more than sweat and blood to make them run. Plympton strikes me as the type of artist who rather wing it than refine his raw talent through discipline.

Far too often Cheatin’ plays like a storyboard in motion. Instead of watching a movie and falling enchanted with its unique perspective, I’m repeatedly yanked out of the experience by Plympton’s self-advertised exertion, his supposedly all-eclipsing toil to bring the project to us one frame at a time. There’s still something to say about those craftsmen who erase all effort from their work. Like any editor worth their salt will tell you, the audience shouldn’t have to notice the cuts. Like growing conscious of your blinking or breathing, I noticed the cuts—so to speak—and lost all awareness for the project and its world to focus predominantly on the work’s roughness.

This is purely a matter of aesthetic preference. There are plenty of people out there willing to trip over themselves to tell you that Plympton’s ragged style is indicative of the emotional mayhem plaguing his character’s inner worlds. Fine. I can see that. But it’s far from the complete truth. There’s no ethic here, not only in the draughts, but in the writing, too. Much of the film runs arbitrarily. The pacing expands and collapses like that of a tinny-eared amateur’s accordion. No rhythm, no melody. No sense, no reason. It’s that lack of attention to structure that bleeds over and hobbles Plympton’s art, too.

Plympton could benefit from a little Altman-like collaboration. He needs to expand his scope—find inspiration from others—before winding himself down a rabbit hole of self-indulgent hackney. With an outlook this outlandishly loose and free, it’s disappointing to see it squashed so narrow by uncertainty.