By Mikhail Karadimov January 27th, 2016

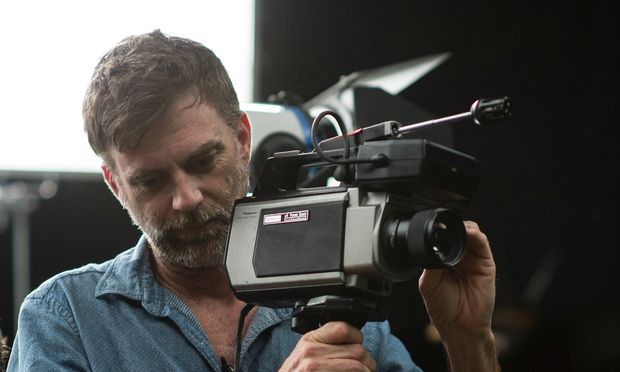

This past Sunday James, Parker, and I recorded and released an episode discussing Paul Thomas Anderson’s latest film Junun. In the episode there were certain criticisms—be them constructive or otherwise—lobbed at Paul Thomas’s wonderful and kinetic film, and I would like to address them, since I unfortunately did not have time to collect my thoughts into a cohesive whole.

The thing to understand about loving a director, about worshipping at their altar, is that there’s a relentless passion to the love that is sometimes blindingly dumb. They render you mute. One of the reasons I love Paul Thomas’s movies so much is that they’re nearly impossible to digest in one sitting. Much is to be mulled over, picked apart, rebuilt, picked apart again, re-examined, and then, years after the fact, you’ll watch either The Master or Punch-Drunk Love or Inherent Vice, and you’ll find that all your brilliantly elucidated ideas and analysis is no longer relevant, that the movies have somehow continued to grow and evolve into a piece of work that has long transcended its original ideas.

One of the remarks made in relation to Junun is that the film doesn’t carry the prototypical Paul Thomas stamp of visual aesthetics. It’s worth mentioning that even though filmmaking is a visual medium, it is also a medium predominantly governed by storytellers. At least popular filmmaking is. And within that realm of storytelling there are the ideas, the themes, the motifs, the patterns that go along to bolster the visuals with context. A filmmaker can’t avoid him or herself while writing their scripts, they can’t escape their subconscious, their kinky likes and dislikes.

And so it is with Paul Thomas and Junun.

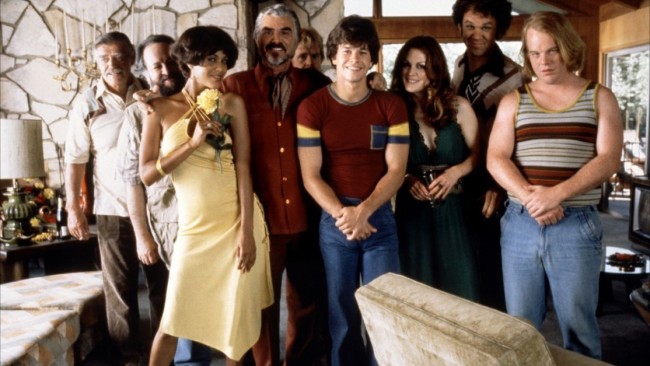

Paul Thomas has always been fascinated with the motif of strangers collecting together and creating their own makeshift family. Be it the dysfunctional, incestual revelers of the Boogie Nights clan or the coterie of runaways and propped-up misfits of The Master, Paul Thomas depicts his ensemble of characters as broken people in need of supplemental and emotional support from others—from like minded people, fucked up people, people yearning for family ties. Junun depicts a similar connection between its culturally and religiously disparate musicians. Greenwood and company are from different parts of the world, of varying belief systems, of opposing musical sounds, of East and West, of conflicting tongues and languages, and yet, despite it all, they are joyously entwined by this ethereal connection—these beats and melodies—that surpass mere differences and take into shape something like a strand of coiled DNA, a universal DNA that programs us to move and sway and nod to even the simplest of rhythms.

As mentioned in the podcast, the film’s title—Junun—roughly translates into wild passion, obsession. And the film depicts just that: the obsession of one’s craft. We rarely see these musicians far from the room in which they record, and if we do see them outside of it, we see them on the prowl for new instruments, new sounds, something—anything!—to help them with their album. We see Paul Thomas—behind the camera, of course—running around with the frame, with his compositions. We see how he re-sets the camera, how he creates shots on the fly, how he obsesses to find the perfect sequence of images for each and every track.

And yes, part of the obsession, is always the craft, the little moments of imperfection and perfection, and how we strive to achieve the impossibility of perfection. You see people struggling with perfection and craft throughout all his movies. You see it as Jack Horner grows weary over the transition of porn from film to video tape, you see it in the way Lancaster Dodd sweats and screams and fights off any and all criticisms leveled at his new book, you see it when Barry Egan tries to repress his sexuality, tamper it down with a late night phone call gone wrong.

On a more technical and aesthetic note, Paul Thomas has always been a director with a great musical ear. I mean, it’s literally the reason why Junun exists: his relationship with one of the best working composers: Jonny Greenwood. But even before his partnership with the Radiohead guitarist, music has held a distinct hold over all his films. While watching Paul Thomas’s movies, I often have trouble separating the song or piece of music from the image. No where is this relationship, for me, more indelible than Punch-Drunk Love, which is wall-to-wall crammed with music. The film might as well be a musical, which it sometimes is—the way the camera glides in real slow, like a saunter, as Adam Sandler’s Barry Egan tap dances up and down the aisles of his local supermarket. Hell, the very thing that sets Barry Egan off and turns him into Superman is the beat-up harmonium he finds abandoned on the side of the street. A harmonium…harmony, anyone? Even his camera knows how to move according to the music, how to waft like a lyrical note, how to lift and fly on the back of a bird’s wings, just as it does in Junun. In Junun, he wants to see how music can float, how it can take to the skies and swirl and dive and rise again, like the very birds that swirl the tops of Mehrangarh Fort in search of fish chunks.

Now, as for the charge that the film doesn’t look or feel like a Paul Thomas Anderson film: a few things worth mentioning. Paul Thomas, other than Boogie Nights—is used to a slower pace, typically dictated by character’s revelations rather than plot machinations. Most of them run over two hours and have the ability to breathe with great breadth. Alas, the film was made on the fly, at the last minute, and runs at fifty-minutes. Paul Thomas simply can’t luxuriate as he usually does, concerning himself with framing and lyrical compositions and frame shots and steadicam shots. But hey, last time I checked, rarely—if ever—has their been a perfectly shot doc especially when the doc in question is held slave to a time constraint.

Furthermore—and this was mentioned on the podcast, too—directors—the great ones—and of course this is an opinion, but one bolstered by many, many years of watching movies—don’t force their aesthetic on the content, but rather, they massage it into the content. They ease the style into the content. No two Paul Thomas movies look alike, nor do they play at similar speeds. Boogie Nights is like a road-burning Porsche, while Inherent Vice plays like one big slow zoom-in, into the haze of weed and intrigue. Paul Thomas always knows the story he wants to tell, but more importantly, he knows HOW to tell it. The visuals marry the story, not the other way around. It’s that versatility, that adaptability, that caused me to fall in love with his movies in the first place—that knowledge that I will never get the same film from him twice. The Master floats and pirouettes and glides everywhere, like a dream, like a boozy reality where the surreal slowly starts to bleed in with the real. There Will Be Blood is played a little more static, with more composition and framing, with sharp lines and diagonals to block and cut the frame; like its lead character, it plays methodically. So if you ask me whether or not Junun feels like a Paul Thomas movie, I’m inclined to say, “Yes, it most certainly does.”

Jonny Greenwood and company are here to create, to search and locate, and then bring to life the notes swirling from their heads, to their tongues, to their finger tips. They are there on the ground-level constructing an album, and so is Paul Thomas, constructing his movie. And we see that construction in meta fashion, like showing a take that documents how that very camera is set up and then reset elsewhere. We see the reset, we move with the reset, we don’t just cut through it. We see the human error. Just as we see one of the female vocals fuck up a line and shove it back down her throat. That’s why we see the musicians tuning up and asking one another whether the sound is right. They’re in search of their album, like Paul Thomas is in search of his 50-odd-minute doc. We’re on the ground, in the room, right there with them, with the pigeons that add to the flavor, the ambience—the very same pigeons that then fly out the window as Paul Thomas’s Go Pro drone does, which can not—in any way, shape or form—possibly be considered an “accident” rectified by the editor, as suggested by one of my co-hosts. The editor wasn’t there to ask Paul Thomas to pay so much attention to the birds and how they relate to the musicians and their music and their chamber, the editor wasn’t there to suggest he hang the drone in the middle of a hurricane of birds in frenzy. Just the fact that there is so much attention paid to birds and flight and music—which has been described to waft and float by many writers past and many writers to come, I’m sure—sparks an undeniable correlation.

Mind you, The Master wasn’t glowingly well-received when it first came out, not right away. At first, there were plenty of critics who didn’t care for a movie that seemed “revelatory in the moment” but “obvious in retrospect”—as written by Michael Nordine at L.A. Weekly. Many of them didn’t want to bother with a movie that they would have to watch twice to understand. Even Roger Ebert couldn’t see through the mist: “It is often spellbinding. But what does it intend to communicate?” People didn’t know what to make of The Master. Nor did I. I knew I liked it, but on a primal level, not an intellectual one. (Which, when it comes down to it, especially as someone who intellectualizes most movies and books and personal events in my life, I treat as a welcome reprieve.) However, now everyone thinks The Master one of his better, more masterful—(yes, yes, I know)—pictures—or at least good enough to be featured at The Museum of the Moving Image’s 70mm retrospective last year. I’m not saying Junun is nearly as good as The Master. Not at all. What I’m saying is: I don’t yet know. If I’ve learned anything from watching Paul Thomas’s movies over the year I know to take my time before making any bold statements about its relevance to my life and his greater body of work.

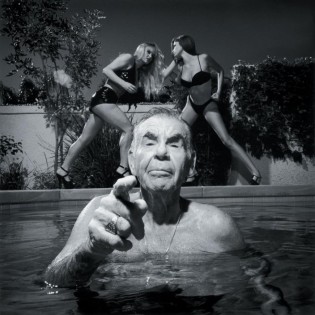

Now, one last point: it was also stated that Paul Thomas had mentioned in an interview how there were some things in Junun that he wish he could have done differently, shot differently. Given his brief window of production and the dwindling time left on the album’s recording, it goes without saying that there was bound to be regrets and missteps. To say that these “rushed” missteps somehow harmed the film is ludicrous, especially when his main objective was to place us, the audience, in the room for these recording sessions—and one jam session, which can be found in the scene immediately proceeding the charged opening number, where Shye Ben Tzur fiddles with his electric guitar. The movie is scrappy, as any thought process or creative process is scrappy. But that’s not the point. The point is, Paul Thomas isn’t the first director to have ever admitted to disliking portions of his films. Woody Allen is notorious for hating most of his movies. This is what Woody Allen has to say about Annie Hall—supposedly his masterpiece: “In the end, I had to reduce the film to just me and Diane Keaton, and that relationship, so I was quite disappointed in that movie, as I was with other films of mine that were very popular.” And how does he feel about Hannah and her Sisters? “Hannah and Her Sisters was a big disappointment because I had to compromise my original intention tremendously to survive with the film.” Does this change your opinion of either movie? It probably doesn’t. What a director says about their own movie should often be taken with a grain of salt. They’re often too close to the project to find the artistic merit in it, especially if their egos are in check with a dollop of humility. Bergman, too, had plenty of trouble watching his movies once they were in the can. He’s called films like The Seventh Seal and Smiles of a Summer Night infantile in their philosophies and execution. Does that mean they’re any less masterful? Hitchcock didn’t like Rope. Do we necessarily need to agree with him? Tony Kaye can’t stand American History X. Should that make the movie worse than it actually is?

In short, I don’t know if Junun will go down as one of Paul Thomas’s best. Probably not. But maybe it will. Who knows? What I do know is that this is a Paul Thomas Anderson film and it’s a film that understands its content and, more importantly, understands its limitations, and despite those limitations it still finds a way to adapt, to remold, and express itself uniquely and with cohesion while drawing a parallel to the musicians’ feelings and sentiments with those of our own—the audience. And for that to have been done—and accomplished—with everything going against it, I believe it’s worthy of my ovation.