By Mikhail Karadimov November 11th, 2015

Not too long ago—maybe a week ago or so—you could watch Paul Thomas Anderson’s latest on MUBI.com. Love MUBI. Love what they’re going for. Each day, a new movie appears in a 30-picture rotation as another is discarded. There are only 30 movies at any given time, and they are selected with thought and a sense for curation. It was because of PTA’s latest, Junun, a story of Johnny Greenwood—the composer of PTA’s last several movies as well as the lead guitarist for Radiohead— and his collaborative trip to India that I even decided to purchase a membership to the site. (I highly recommend it).

Either way: it took me several weeks to finally sit down and watch Junun. I consider myself a pretty big PTA fan. Whether or not I’m one of the biggest is up for debate. I surely didn’t do much to prove it this time around. I don’t know why I hesitated for so long to watch Junun. There seemed to have been so much pressure behind the decision. I needed everything to be perfect, for the environment to glow with the right aura, for the screen to stretch wide enough, high enough, to validate a viewing. I refused to watch it on my laptop, in my hotel bed, with my headphones on, as Chattanooga droned on with its boring buzz, with all those trucks and sedans waiting and honking on line for their fast food orders.

The scene needed to be right. And it wasn’t. But then I came home and I finally tried, I finally summoned the energy to watch PTA’s side project, his practice, and geared it up, only for the internet to fail and stutter and break my viewing into little jagged pieces. The rhythm was shot.

I thought it karma, I thought it comeuppance. The gods knew I could’ve and should’ve watched Junun by then, but I had hesitated, I had faltered and fallen, and because of it my rhythm, and the movie’s rhythm, started and stopped, it hiccupped along. Everything was out of tune, out of whack. My ear lost its equilibrium and I spun off into anger.

For the first time in a long time, PTA and I had lost or forgotten our harmony. He forgot how to present, and I forgot how to watch.

It was another week before I managed to heal my ego and give Junun another go. I thought about how my finger tips would callous over every time I tried to teach myself guitar, and I looked at my fingers and could see them in their old practiced state, I remember how wonderful it felt to rub over them and feel the vague remembrance of touch behind the dead skin cells. I thought to myself: maybe I’m ready now, maybe this is the place, the time, maybe I can show my love, my respects, and give Junun my full attention.

I ritualized the screening. I prepared food, brought napkins for the nightstand, straightened the sheets on my bed, situated my old man’s pipe and weed for easy access, filled several bottles with water, connected my wireless Beats vie Bluetooth, calibrated the thermostat to reach and maintain a steady 73-degrees. I tuned my surroundings, listened and felt for the perfect note of comfort.

And then I pressed play.

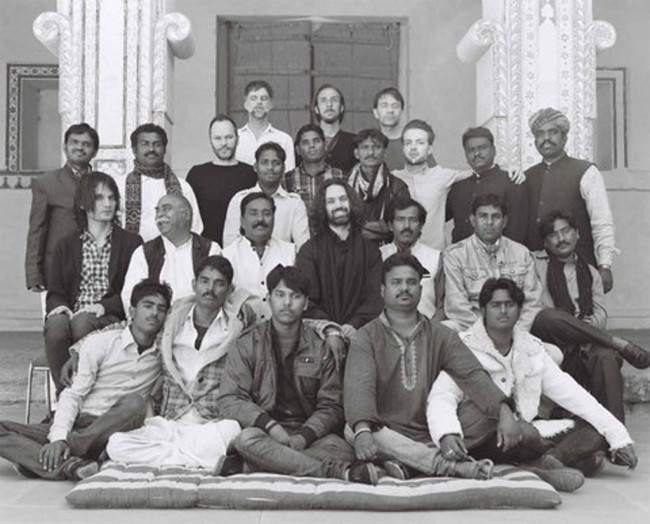

The mission is music. Johnny Greenwood and Israeli musician Shye Ben Tzur, accompanied by a retinue of traditional Indian musicians, practice and record and rest in a mason sanctuary, Mehrangarh Fort, in Rajasthan, India. There’s barely any dialogue, barely any trick photography, all that’s there is the music, the chemistry, the intertwining of notes and chords and people and touch, of checkered religions, traditions, cultures, and how all these seemingly contradictory sounds can find safe haven in a place forgotten by time and the governance of time as well as the usual presuppositions that guard a man from easy communicability.

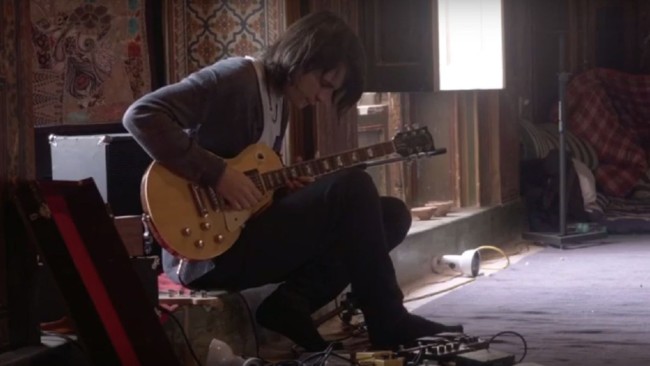

This isn’t a Paul Thomas Anderson picture, nor is it really a picture, nor a traditionally told music doc. Greenwood and co.’s inner sanctum, their playing room, which is laid thick with rug, and where pigeons come to recover and coo and lace the band’s sounds with fluttered ambience—this is where the magic happens, where harmony is found and issued, where it is channeled; it is in this room that everyone finally masters the art form of telepathy and swings in unison. This is where hate and pettiness comes to die, where there is a singular goal that everyone, in unison, strives to adhere to. But the musicians and their music don’t confer solely with other members of that inner sanctum, it spills beyond those rugs, those walls, and it rubs up against the many people who visit the fort on a daily basis. It even touches one man who belongs to a long line of fathers and grandfathers who have made it their duty to arrive to the fort’s summit every day and feed a flock of birds that frantically fly claim to the fort’s many turrets and high perches. He keeps with him several buckets of fish chunks that he casually offers to the sky and to the swooping birds that catch the feed in mid-arc and then fly off and swoop back for more. A swarm of birds, a chaotic dance that’s ultimately governed by harmony, by tuned-in chords. Despite the scramble, the anarchy, these birds never hit each other or wing another’s beak, they scarcely ruffle their neighbors’ feathers. They know where to go, how to move, where their fellow bird’s trajectory will lead them next. They’re communication, like Greenwood and co.’s, rarely relies on speech. They don’t need to squawk to strike synchronization.

The film plays simple. It play succinct. Without overstaying its welcome, Anderson’s camera is unassuming, a grateful bystander in search of magic, of that heavenly spell. And he finds it. But only because the camera never wrestles to find it. Anderson wants to shoot. That’s all he wants to do, and he wants to do it without the burden of a full blown production. He wants to fly high and find his nadir, but he can only do that once he loosens up and lets go and just shoots. And he finds it here. We see a director that still has the bug, who still flames those adolescent urges to do, and just do, and to shoot with a clear sight, with a simple mission, with a wandering focus that knows what it’s looking for without knowing everything. The man wants to keep form and he certainly does so—all the while: reinforcing that notion that no other director working today comprehends the musicality of film the way he does.

The movie rings mellifluous. Sublimity caught in motion.